It was the summer of 1975, and the mountains above Pasadena buzzed quietly with anticipation. Nestled in La Cañada Flintridge, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory—JPL—was already a place of legends, filled with brilliant minds dreaming of the stars. But despite all that technical firepower, there was one problem they couldn’t solve on their own.

They couldn’t watch their own rocket launches.

The irony wasn’t lost on anyone. Here were scientists and engineers who could send spacecraft millions of miles into the cosmos… yet they couldn’t get a clear TV signal on the very hill where history was being made. The mountainous terrain blocked over-the-air broadcast reception, leaving mission control blind to what the rest of the world was seeing.

That’s when they turned to the cable industry.

And that’s where we came in my boss and mentor Ray Tyndell and myself.

Just a young guy in the business back then, I was part of a two-man crew working tasked with running coaxial cable—good old-fashioned analog lines—up into the heart of JPL. We weren’t bringing space-age technology with us. No satellites, no lasers, no fiber optics. Just reliable coax cable service and two determined techs who believed in getting the job done.

We spent days snaking lines through the rocky terrain, connecting television sets in conference rooms and mission control centers. It was simple work with a profound purpose. By the time we were done, JPL could finally watch what they had launched—live, in real time, just like the rest of the country.

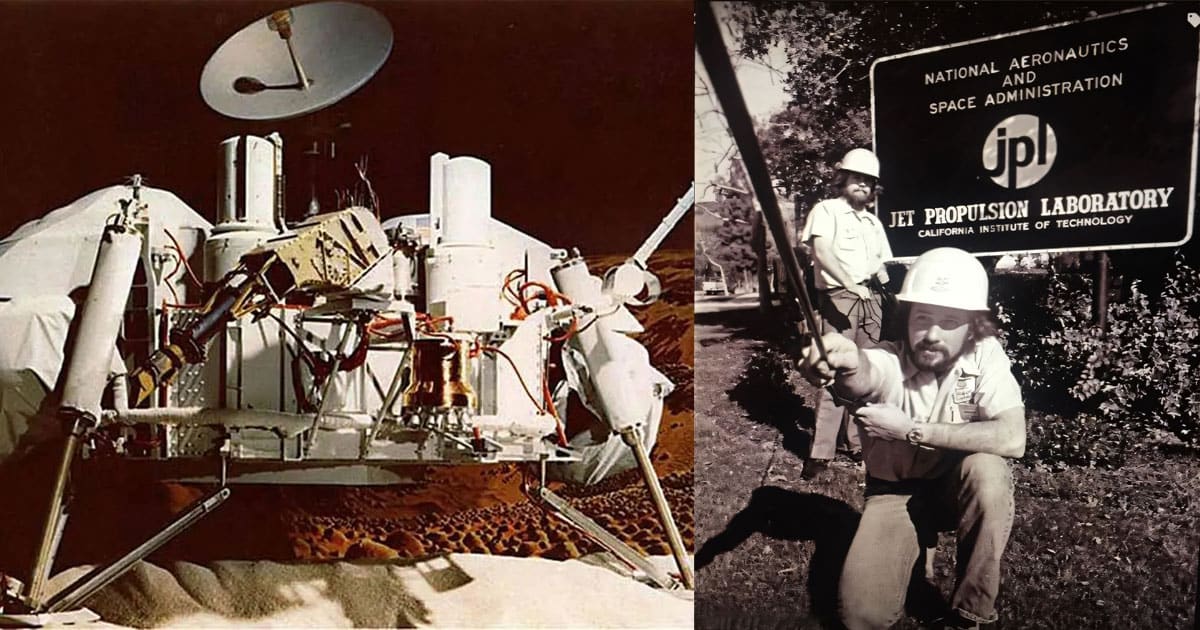

After we completed the work, they gave us a tour of the facility, showing us the original Mars lander and explaining the communications equipment it was being launched with. One of the most fascinating items was a large metal disc that resembled a vinyl record. This disc, known as the “Golden Record,” was a 12-inch gold-plated copper phonograph record containing sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth. It included 115 analog-encoded photographs, greetings in 55 languages, a 12-minute montage of sounds on Earth, and 90 minutes of music. The idea was that, should the spacecraft be found by intelligent extraterrestrial life, they would have a snapshot of humanity and instructions on how to play the record.

Security was minimal in those days—there was no need—so we had open access to all locations throughout JPL. Their operations people were proud to show us around and tell us what they were doing.

There’s a photo from that job that I still keep. If you squint hard enough, you might spot a skinny kid in the background, all concentration and ambition. That was me. Proud, excited, and with absolutely no idea that I’d still be in this industry fifty years later.

Fast forward to today. NASA just landed another Mars rover—this one capable of sending back data, high-resolution images, and even video, nearly 296 million miles from Earth. It took over seven months to reach its destination, and decades of planning, refinement, and technological evolution to make it possible.

And as I watched the news, I smiled.

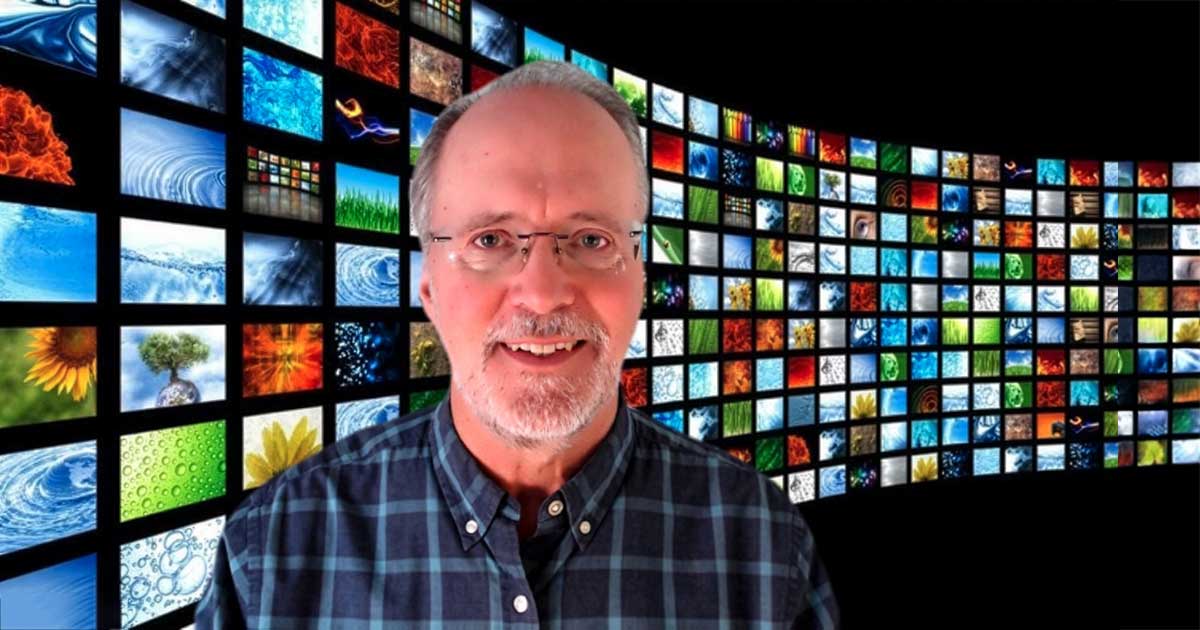

The cable industry has come a long way since then. From basic TV to VoIP, IPTV, 10Gbps high-speed data services, fiber networks, enterprise services, and supporting 5G infrastructure—we’ve quietly helped power the very systems the world depends on, day in and day out.

I’ve been proud to be part of it.

Not just on the days we climb mountains,

but every day since.

EVP, Chief Technology Officer

Astound Broadband (Patriot Media / RCN / Grande/ Wave)