In Memoriam

1935 – 2018

See bottom of page for full memoriam.

Interview Date: Wednesday June 20, 1990

Interview Location: New York, NY

Interviewer: E. Stratford Smith

Collection: Penn State Collection

Note: Audio Only

SMITH: This is Tape 1, Side A of the oral history interview of Les Read of Home Box Office. Les, what is your official title?

READ: Director of Special Projects and Promotions at HBO. I am in the Marketing Department.

SMITH: We are in Mr. Read’s office in the HBO Building at 1100 6th Avenue, New York City. Today is the 20th of June, 1990. This is one of a series of oral histories of pioneers and leaders in the cable television industry that is being done under the auspices of the National Cable Television Center and Museum at Penn State University. Les, the usual procedure is to start at the beginning. We might as well do it that way. Would you tell us when and where you were born?

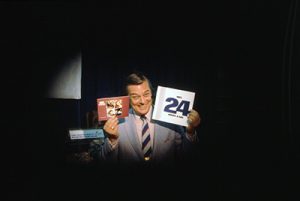

READ: We should mention that Dick Tracy just opened in the movie houses, so if anybody really listens to this they’ll realize at what point in time we are. In the beginning, September 12, 1935. I was born in Long Island in a hospital in Mineola, New York. My parents were both kind of new to this country. They both came from England. They were living in a town called Great Neck. My dad had been in a service station operation. He had started with Henry Ford way back when he (Dad) first came off the ship. He was running service stations in Great Neck, Long Island, New York, as we refer to it. I grew up and went through the local public school system and from there, Great Neck High School. I graduated from high school in ’53. I was a heavy duty, arts-area, hands-on person because I was great at print shop, and auto mechanics I and II, because my dad had service stations. I wasn’t quite sure where I was going to school, at that point, but I knew I better do something. As life goes on you have to compete with people. I felt it was important to get a good, solid, basic business background. I went out on my own, unbeknownst to my family and got enrolled at a junior college in Dudley, Massachusetts. In those days it was Nichols Junior College. It is now a four-year school, and it is also coed. It was an all boy school then. It always felt to me when I first got there like a school for wayward boys. We had our opportunity to get that firm foundation of business. That’s what I was really there for. I learned how to become a pretty decent student while I was there.

Based on that basic training, I transferred to Syracuse University in 1955. I was in business for a year and then transferred to the school of speech because they had the major in radio and television, which was my interest at that point. In the back of my head I still, to this day, have a great romance for radio. I’ve always felt I should be on the other side of that mike talking to people in radio. I did the rest of my degree requirements at Syracuse and graduated from there in January of 1958.

SMITH: What was your degree when you graduated?

READ: In those days we called them BS degrees. Bachelor of Science.

SMITH: That was it.

READ: That was my educational background.

SMITH: Les, we jumped a little bit. You said both of your parents were of English background.

READ: They both came over about the end of the ’20s, I guess it was.

SMITH: Were they married at the time they came over?

READ: No, they got married here.

SMITH: Did they meet here?

READ: They had met very briefly over in Liverpool where my dad was from. Then they met each other again over here.

SMITH: Was the meeting over here a planned one as a result of the first meeting?

READ: No, actually, it was through another friend that said, do you remember meeting Charlie, etc. They were kind of brought back together with another three couples that were living out in Long Island at the time.

SMITH: You say your father was in the service station business. Gasoline service station type with Henry Ford.

READ: Well, actually that was his first job with the Ford garage in Great Neck. He had met the whole Ford family back in those days. Those were the days of the Model “A”. That was one of the first cars I learned how to drive. It was based on that experience and his ability to manage people that he felt that it would be a good area to get into in the service station business. He was one of the first operators in Great Neck, Long Island. As a result, he did thirty-three years with the Gulf Oil Corporation running a couple of service stations in the Great Neck area.

SMITH: Is your father still living?

READ: No. My dad and my mother both passed on.

SMITH: Les, do you have any brothers and sisters?

READ: I have a sister, who I am always pleased to say is my older sister. It bugs her a little bit. She’s three years older than I am. Throughout the course of my career in cable, I have ended up living today, about six miles from my home. Or just about a mile across the bay, actually. I am in a town called Port Washington, which is my present residence. But my sister has also ended up in the next town from there. So we have always stayed close as a family. She is married to a gentleman by the name of John Saunders, who has quite a career in construction. He has run one of the largest construction companies in the greater New York area. They have two children, a daughter and a son.

In my own family situation today, as we go through the travels down the cable highway, my wife is from Great Falls, Montana. I met her when I was on an assignment down there building a cable company. We have four children, which as of today’s date is 1990. The youngest is a ninth grader and fourteen years old.

SMITH: Would you give us their names?

READ: That’s Jennifer. My youngest son, Charlie, is fifteen years old, and doing about everything wrong as a fifteen-year old would do right now, I guess. I’m sweating out final exams with Charlie. Then I have another daughter, Elizabeth Ann, who is twenty-one. Scott Howard, number one son, just graduated from Syracuse University with an international degree. With an international degree, he is headed to Boulder, Colorado, according to him, to find himself.

SMITH: That figures.

READ: I said whenever he’s ready for a reality check, he’d better leave in a hurry. It’s funny, because in a brief number of conversations that we’ve had–he’s been out there now about a month–he is getting used to not having to go to school but he’s starting to ask some questions about the cable industry and who do I know out there. He’s thinking about getting legitimate and finding a job.

SMITH: I’m sure he’ll do that too.

READ: I hope so. But he’s on his own nickel so I don’t worry.

SMITH: Les, let’s go back to your boyhood for just a moment. When you were growing up, did you have any special interests and hobbies?

READ: As I remember growing up, there were a couple of areas. Sports-wise, I loved to ice skate and swim. I ended up doing both of those things to make money going through high school and college. I was a lifeguard for five summers and I was a skating instructor at a rink in Great Neck where I was raised. In terms of high school sports I participated in everything. I played one short season as a football player. My dad seemed to think that if I was healthy enough to go out there and get banged around I should be healthy enough to come down and give him a hand at the service station. There was more encouragement to go to work at that point. I worked quite a bit at my dad’s station. One of the key things I have learned over the years was the service business and dealing with customers–even when they come in for silly little things like gasoline–which today is dramatically changed from what it used to be. You pulled into my dad’s station and you knew the customer’s name and you greeted them. You didn’t ask them if you should check the oil. You checked the oil. You checked the tire pressure. You provided service. Those people kept coming back. That’s why dad was so successful in the area where we are. We are about twenty-two miles out of the city. You had a husband working in the city, a spouse with a car, children with cars; he had service when they would call and say, “Charlie, pick up the car and take care of it.”

SMITH: He’d sell you a gallon of gas for twenty-five cents.

READ: Yes. And you had to have your A coupon, too, if you remember those. That was, as I have always felt, over the years, even in my job today dealing with special projects and trying to get the cable operator to do a better job of promoting number one, his own cable service along with HBO services. You have to think about that guy, the viewer, and how does he react and how does he think. It’s not a lot different than that person who used to come in and they weren’t stunned when you had a rag in your hand and you would wipe off their headlight. They came back. They liked the service. He sold a lot of gas. I mean it was a couple of thousand gallons a day in this particular location. So, it wasn’t a small operation.

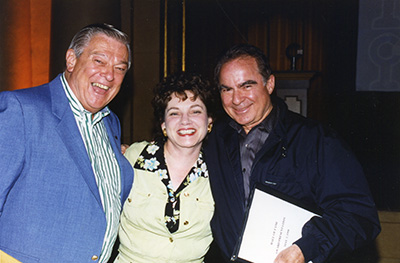

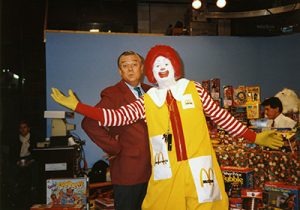

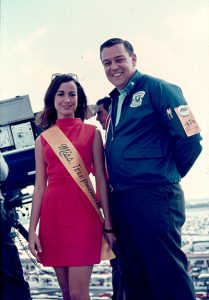

You had another question, too, about my boyhood. One of the things I was fascinated with was sound. In my day it was called hi-fi. That became a nickname of mine because you’d walk into my room and I’d have sixteen or eighteen or twenty speakers, monaural, in those early days. I had to have a good sound system. I loved photography. I have always enjoyed capturing whatever the opportunities and the moments are to take pictures. As you can see with the memorabilia I have around the office here, I love to keep track of all the places I’ve been and the highlights and the opportunities of having worked with so many fine people we have in the cable industry. I think, really, at this point–I think it’s thirty one, thirty-two years–I have been involved, or as you so lovingly say, “You’ve been around forever.” I’ve had a great rocket ride, as we say, in life and the cable industry. So I’ve got a lot of the photos and I like taking photos. I’m almost as bad as Burt Harris.

SMITH: You and Burt would make a good team. Les, how about military service?

READ: Yes. I had a very dear friend. I was a junior in high school and he was a senior. The Air Force Reserves had a recruiting program going on and if this fellow brought in a recruit he won a free trip to Miami, Florida on an air transport plane. In those days they were called C-119 cargo carriers. I was it. I was the recruit that he brought in. I got him to Miami.

I joined the Air Force Reserves when I was a junior in high school and went faithfully once a month. We had our weekend meetings and I got involved, interestingly enough, in communications. It was my first assignment. I later went on to get into air traffic control and, as we said, “sat in the hot seat” and dispatched, took flight plans, and all that information. I enjoyed that very much. But I did all of my eight years in the Air Force Reserves. It was all through the reserve program and when it came time–I had just graduated from college–and I had been back out for a meeting and suddenly I had a draft notice. You know, “greetings from the president.” I said, “Gee, after all this time I get drafted.” Well, every officer in the organization was ready to kiss me off and said good luck. Hope you enjoy the Army, after all my years in the Air Force. There was one well-fed recruiting sergeant sitting in the corner who said, “Hey, junior, what’s your problem?” How happy could you be if you had one of these announcements, which is the greetings from the president. He just casually looked up and said, “They can’t touch you.” This was old Sergeant Gottfreid. I sent him half a case of scotch because he was right. Because of my time and number of years of service, there was a presidential order that said, no he can’t be drafted as long as he continues to serve. Which I did. I didn’t do active duty, per se, but I did my monthly and two-week encampments throughout the summer. I was quite proud of that time, and again, it was another great experience where I learned how to deal with people and get on with people of all different levels of educational and economic background. Damn good experience.

SMITH: You indicated a moment ago that you have a love for radio. Did you actually ever get on that mike and operate a radio station?

READ: Never really quite radio. After I graduated from Syracuse University–it was January of ’58–I said, “Gee, here I am in Syracuse.” I knew you couldn’t really break into the media in New York City. You’ve got to go out to the boondocks and sweep the floors, clean the windows, call on people, answer phones, etc. I said, “Gee, maybe while I’m here I should go to this radio station and just see if they have an opening.” It’s quite funny today because I’m so close with the Newhouse organization through their New Channels and Vision Cable. It was the Newhouse radio station in Syracuse. The head announcer was Floyd Ottoway, and he said, “Hello, you have a nice voice.” I said, “Thank you very much.” He said, “Here, read this.” He gave me a list of about thirty-seven to forty-three classical composers and he said, “Read it.” I said, “Read it, I don’t even listen to this. I don’t know these guys.” I knew I was just going to kill the names. That was my close brush with radio. I have, over the years, continued to do a lot of radio interviews whenever I get to communities and towns where I’m working with cable operators or special projects that I do with Home Box Office. I love to get into the radio station, whether it’s call-in shows or what, and do the radio thing. Radio still has a great deal of imagination to it.

SMITH: Les, let’s go back and talk a little more about your wife. So far all we really know about her is that you met her in Great Falls, Montana. Tell us a bit more about her; how you met.

READ: Her name is Ann Marie Erickson Svenska. Her family came from Minneapolis and moved to Great Falls, Montana. Her dad is a great outdoorsman; loves to fish and hunt. His world is to go sit in the boat and fish or go hiking through the hills. He didn’t like the restrictions; he’d been on a farm outside of Minneapolis. He decided that wasn’t the area for him and he put the family in a trailer and he moved to Great Falls, Montana. He was also a very talented carpenter. When he got to Great Falls, in those days it was a very tough union state, he balked at that. He ended up going to work for the school system as a carpenter and did his whole career in custodial services rebuilding door frames and cabinets and doing his carpentry work for the school system.

Ann went to schools in Great Falls. Her two interests in life were nursing–she did a candy striper job at one of the hospitals in Great Falls–and she was blessed with a magnificent voice. She decided to expand and grow and she did quite a bit with voice lessons. She became one of the key singers around Great Falls, where she was always getting asked to sing at somebody’s wedding, at funerals, or whatever the event that might be going on in a community such as Great Falls. She was kind of following a career in classical music. She was looking at the Northwest Metropolitan tryouts and she was on that course. She had gone to the University of Montana in Missoula. She had first gone to a school in Nevada, Missouri–Caudy College. It’s a school run by PEO’s, which is a very special organization.

SMITH: What does PEO stand for?

READ: I don’t really know. It’s better than a sorority, I guess. But it’s all for development and growth in the educational field. She was fortunate to have some assistance in a scholarship program to go to Caudy College. She finished there and then went to the University of Montana in Missoula and graduated with a degree in education. She became a music teacher in the Great Falls school system. In those days, it was a traveling job where she had twenty different elementary schools. Each school didn’t have a music teacher so she was the rotating teacher. She would go in and teach some courses.

To make a long story short, she has since gone back recently–two, three years ago–and gotten a master’s degree in music education and is working in a community next door to ours in Long Island. She is developing new music programs for handicapped children. Music is still a marvelous, magical way to reach kids with great problems, great learning disabilities. When they can’t think through problems, you can reach them through music. She has developed a number of programs and is also still doing a couple of different schools, so she does her traveling routine. She is still involved musically. She is one of the lead sopranos with the church choir, she is with a Queens Choral Society, which is a fine, outstanding choir that operates out of Queens College.

She has gotten very involved with the head of the music department at Queens College and she works there on a Saturday project for an advanced program. If you’re at all familiar with the Suzuki method, at two years old they give you a fiddle and say just go ahead and fiddle and by the time they’re six or seven they start sounding pretty good. It’s the same type thing with voice that they’ve been doing. She has developed this program with a professor. It’s quite an advanced program in music and she’s one of the instructors and teachers there. So she is quite dedicated to music, along with trying to keep track of a fourteen year old and a fifteen year old. I guess it must be like flying a P-36 and you take a few shots off the wing and it starts going down. Our daughter has just decided she is not going to take any more piano lessons at the age of fourteen. No more piano. So the mother is a little broken hearted at this point. But my daughter plays a pretty good piano.

I think that’s about complete on Ann. She came from Great Falls. It was kind of funny because my dear, sweet, little old English mother, who was 4’11”, used to always say, “Son, you’re going to meet the nice girls at church.” Needless to say, I met Ann with a couple of other gals who had gone to a movie and had gone in to have a beer at Duffy’s Tavern in Great Falls, Montana. So when I called home and said, “I have this new girlfriend”, my mom said, “Where did you meet her?” I said, “St. Duffy’s, mom, St. Duffy’s.” Eventually, a year later when we got married, both my mother and dad came out for the wedding and the first thing I had to do was show mom St. Duffy’s. We didn’t have a chance to go in and have a beer with mom but she got a real rip out of that one.

SMITH: You describe your wife’s interest in music and the uses to which music can be put to get to problem students, children who are not otherwise easy to communicate with. Has she done any publishing in that field?

READ: No. No publishing. She designed the course material but nothing has been published at this point.

SMITH: Let’s just take one step back to your own college activities. Did you have any special interests while you were in college other than just studying and getting your degree and getting out?

READ: Let me jump back to Nichols College where, as I meant to say, I was really an industrial arts major in high school. And here I am trying to get a basic business foundation and also having to learn how to study. My first semester I did everything I could just to hang on to make sure I was there for the next semester. Nichols had this very small campus and I got to know an accounting professor, Max Cantum and his wife Katherine, who kind of took me under their wings and said, “If you’re going to survive here’s what you need to do.” It was through the sessions when I would go over to their house in the evening and sit and talk, get involved with the academia that was all around me, I suddenly caught on to how to study and how to get it done.

At that point, I became very involved with campus life and took on a couple of special social committee assignments because I loved to make arrangements and make things happen. Eventually, I became the social chairman, planning three major functions on campus. It was a funny campus. We were close enough to New York that in three and a half hours you could drive down to New York and go to Boston in another direction in an hour and twenty minutes. You were close to the coastline. Not a lot of people hung around the campus all weekend long. We did carry on a very extensive social program to keep people involved. So based on that, I got quite involved in that and that led me into the Green Coat organization, the Justinian Council. This was the student government, which I had the honor to serve for a year and a half. That was pretty much a full time job.

I also, at that point, was still involved with photography. I had a lot of equipment that I kind of stumbled into. Those were the old days of speed graphics cameras and the press camera. I did a lot of photography for the newspaper and for the yearbook. Going over to Syracuse, from a campus where there were three hundred people to a campus where there were twenty-five thousand people, was a real shock. Again, I had to relearn the whole system where you would sit in a classroom with maybe four or five hundred people sitting and listening to a lecture trying to stay awake and then trying to figure out how to answer the questions on test day. That was a new involvement.

I had a friend there, and I was introduced to SAE (National Fraternity of Sigma Alpha Epsilon) and it was that involvement that really took up most of my days on campus at Syracuse. I became very involved with the fraternity, serving in a number of positions, and ending up being Treasurer, which was a delightful job trying to collect money, particularly when you knew the guy was spending his room and board money down at the local pub. But, we did a pretty good job there. Again, being a transfer student I didn’t quite have all of the, as I used to lovingly say, “orange blood” in the system. At Syracuse, everything is orange. Therefore, I put most of my energy towards the SAE house of which, again, I was quite proud. Also, I got involved after I graduated from Syracuse working in a regional capacity. It was my first trip to State College. I had worked with the local chapter throughout Pennsylvania and New York state as an alumni working with the actives.

SMITH: The interviewer shouldn’t interrupt and put words on the record, but I just have to say this. I was also a fraternity treasurer while I was in college and I experienced much of what you were talking about. I was a Kappa Sigma at the University of Utah.

READ: We won’t hold that against you. But you do know. You had to follow people into the john as soon as their car came around the corner. You had to pay the bills and you were sitting there waiting and finally, for a couple of them, I just said, “Hey, I’m going to talk to mom and dad and see if we can’t help you out of a problem.” I made some great friends with parents. They’d send me the check direct.

SMITH: Well, Les, as we have to in these interviews we’ve got to get to the subject of CATV and cable. What was your first employment out of college? You might just start with that and then move on up to your first exposure to the cable television industry.

READ: Coming from Syracuse–having gone through that experience of having to read a list of forty classical composers–because of my family being in the Long Island area, I ended up coming back down to New York. It was January – February of 1958. I went into the RCA Building–as it was called in those days–the home of NBC, and I thought if nothing else I could pick up a job during the season when tourism picks up in New York City in the spring. I walked in and said to the Personnel Department, “What is it I’m going to be, a page or a guide?” The lady looked at me and said, “You mean you don’t want to be the president?” I said, “Well, I’ll work up to that.” She was thrilled and said, “You can be anything you want to be.” So I said OK and I ended up going to work at NBC. This was one of those “entry-level” jobs that you read about when you see a “Who’s Who” of people in the media business, broadcasting, print–any field where they’ve started in New York as an NBC page or guide.

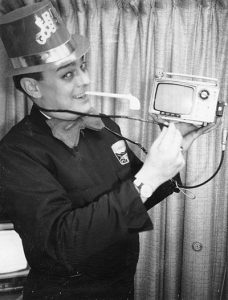

Being the size I am, I had a uniform of some size issued to me. In the breast inside pocket there’s a label and on that label were names of people who had worn that uniform. There was a guy by the name of Dave Garroway and there was another fellow who did the “Do Re Mi” quiz show; he’s been around a hundred years. One of the people who I’ve run into in recent trips and travels in my cable days has been Willard Scott, who is also an alumnus from the NBC page staff.

Not too many years ago they had a fiftieth anniversary of the page staff. It was quite interesting. It was the days when Grant Tinker was still there. It was incredible, the people who came back, when you look down the list of NBC pages and guides who were there.

I ended up working in the Guide Department. Again, the woman said I could probably have more fun being able to use my voice. I was put in charge of taking forty green people from Anywhere, USA–or for that matter, around the world–and walking them through some usually bare studios. You had to make it sound exciting for the two or three dollars they were charging for this tour.

One of the fun stops along the way was the sound effects show that you would put on and that’s where you were able to show your best work. I enjoyed that quite a bit. It wasn’t too long after that I was made the head of the tour group, which gave me the opportunity to work with a lot of folks at NBC and develop new displays. Back in those days, it was a spin on radio.

Of course, television was continuing to grow and grow. We had to handle the assignment of making television sound even more exciting, and show how good RCA color would be so that you really want to think about putting a color TV in your home. We worked on the new displays and brought in some people who had worked at NBC and changed a few things around. After that, they say you have had a year and a half in the Guest Relations Department, as it’s called at NBC. That gives you the opportunity to make enough contacts and figure out what field you want to go into. It was at that time that I also had an opportunity to get into ticket distribution, which was another leg of the guest relations operation. We handled all of the tickets for the Perry Como Show or the Jack Paar Show. There were a number of theatres around New York City where these TV shows would originate. Not all of them originated from the RCA Building. Being a new person in the city, this was an incredible position to be in with all those tickets. You make a lot of friends and meet a lot of people. It was an interesting area, this dealing with tourists.

SMITH: You were in a position, Les, where you personally could make tickets available to people that…

READ: Always had about five or ten tickets in the inside pocket.

SMITH: You must have been a popular man.

READ: Let’s say I did a lot of horse trading in those days. Of course, you had interest from people who would come in and ask how they could get to go see a regular Broadway show, or something like that. So you would have contacts where you could say go see someone. It was through one of these contacts that I met in those days, they were called unit managers. He was a very dynamic guy. He had worked on the Today show. In those days I guess it was Hugh Downs who was doing the Today show. We got into a conversation and I said, “I would really be interested in looking into a unit manager’s job.” This was the interface between the network and the show producer. A Goodson Todman would come in and say we want to put on this quiz show and we need this kind of camera and this kind of equipment. Well, it was the unit manager’s job to control costs and keep track of what was happening in terms of getting the show on the network.

It was through this contact, he called one day and said, “There’s a company that might be looking for a guy like you.” And he said call this number. This was thirty years ago. Judson 2-3800. I can always remember the number. As it turned out, that was TelePrompTer’s number. It was TelePrompTer, which Irving Kahn–the founder–along with Hub Schlafly and another part-time actor who couldn’t remember his lines and needed a device so he could remember his lines had started. Irving, Hub and this fellow started a company and they were looking for somebody to work as a scheduling operator. It was kind of in the area of a unit manager. It was a facilitator, it was making sure you had equipment at all the different studios around New York whether it was the Ed Sullivan Show or the Arthur Godfrey Show or the Gary Moore Show. Gary Moore was a very big show for us. Gary Moore was so blind, he couldn’t see the small print so they had to use special prompters, which were about the size of a suitcase, a little bit bigger than an under-the-seat type suitcase. Those words had to be magnified and blown up so he could read them. Everything he said came off a prompter. There was no ad lib.

As the years went by, you would see the talent become more relaxed, more at ease. Arthur Godfrey finally said, “I don’t need a prompter anymore.” In the early days, everything Arthur Godfrey said was on a prompter also.

But it was through this phone number that led to this job as an operations type person scheduling equipment, operators, network studios, advertising studios, special filming jobs, that I walked over there and met a gentleman by the name of Don Redel. Don is no longer with us. He later went on to end up working for HBO in film acquisition, program acquisition area. Don put me on pretty quick. It wasn’t a very complicated process in terms of interviewing. I did have a resume and he said, “But can you talk? Do you know how to get equipment from here to there?” I said, “Sure.” To make a long story short, I did that for two weeks and he said, “You know, I’m wasting you sitting here at a desk. Go out and sell the prompting service to different shows, different advertisers–get more accounts.”

SMITH: I need to interrupt you Les, because the tape is running out. I’ll turn it over and we’ll continue.

End Tape 1, Side A

READ: Where did we leave off?

SMITH: We are starting Side B of Tape 1 and you were mentioning the fact that the man who employed you, Redel at TelePrompTer, said he was wasting your time having you sit at a desk and told you to go out and sell TelePrompTers.

READ: We had these big sheets where you had to make sure there were enough prompters and that the scripts were delivered on time, and that the operator showed up. It was a hairy operational job. But in time, he said go out and talk to people. With that I started going to a few folks I had made contact with at NBC through my guide days, page days. It was very interesting and easy to get in over there, which helped quite a bit. As I have found throughout the industry, being in both broadcasting from those days and cable for the last thirty years, contacts are so important in this business. What goes around, comes around. People just don’t disappear.

The first really big break I had came when we landed an Olde London food account, which was jellies and cheese crackers. They wanted commercials for an afternoon show that was called “Who Do You Trust?” It was taped at the Little Theatre which is at 44th Street, right next door to Sardi’s. Of course the guys who did that show–they were brand new together–were Ed McMahon and Johnny Carson. My job was to make sure that the scripts were there in the studio. It was an account rep type of situation. That the operator was there, that the equipment worked. Because in those early days of prompting, there was always a lot of problems with equipment. God bless Hub Schlafly and his selsyn motor. It was always a problem keeping these two or three or seven prompters in sync so that it was saying the same word at the same time. Sync was always our problem. Death defying act when it came to prompting.

I got to work that show and did that for a long period of time. I got to know both Carson and McMahon pretty darn well because they would do a run through–they would do about five shows in an afternoon–where you would do a run through and tape the show, run through and tape the show. Between the run through and the tape and a few other times, I always had a little time to run into Sardi’s. In those days when they were really good drinkers, it was time for a little warm milk–yech!! Off we’d go. Well that was the other part of my job, to see that we had a cocktail when we had to have a cocktail. We’d get finished with the taping and these guys would tell stories. Both of them are great, great fans of W.C. Fields. They would be forever just telling stories, remember this story about the time…. and they’re doing this whole take-off on W.C. Fields. We spent a lot of time there and they also loved music. Dixieland was a big favorite.

In those days–this would be ’58–there were a number of clubs on 52nd Street in Manhattan. It was Music Alley. We would end up over there till the wee small hours. Fortunately, I was living in the city at that point so I could crawl home on my hands and knees to get back to face the next morning. It was one of the most fascinating times. As you look back on it, when you were going through it, a job was a job and you were having a good time. It was truly one of the highlights of my career in the early days of TelePrompTer.

SMITH: Would you describe in a just a little more detail the matter of this sync problem? Were several teleprompters in operation simultaneously at different locations in the studio?

READ: Exactly. Depending upon the number of cameras on the shoot, a complicated show like the Gary Moore Show, you would have up to four, five, six cameras. Which meant that the operator of the prompting device had a machine so that he would monitor where it was and he was always following the person who would be speaking. On top of each camera, which is another interesting phase of broadcast history, Irving Kahn had to go in and kind of win over the union camera people and all the union representatives so that we could put a prompter on the camera, which was unheard of in those early days. As only Irving could, he did. It became very much a fixture on the camera. The first couple times around it used to sit on a stand on kind of like a tripod stand and they’d have to wheel this around the studio so it would be right under the camera. Finally, Irving won over the unions to say it’s okay to have my machine on your camera. It was a very hairy problem. On a panel of prompting paper there was a little hole and that hole would go over a special strip–a metallic strip–and until all of the machines held at that same time, it would stop all the other prompters if one was going faster than another one. The paper would go up and it would hit that strip and then they would all supposedly–remember that word sync–run together.

Well, as we lovingly kid Hub Schlafly, it didn’t always quite hold so that one prompter was telling you one thing and another prompter was running a little bit further ahead. It was a tough battle. Of course today, I, in my own job at HBO, do a lot of on-camera work and from time to time get to use a prompter. It’s all done now by video. There’s a small TV camera mounted in front of the TV camera and you just read your script off that. But in those days you had paper with up to seven pieces of carbon and the typewriter would write out in 5/8″ type. One of the most dangerous places when you had pages and pages of script was when one of those typists who would be banging away on this electric typewriter and the key would break and it would send this missile flying across the script department. It was incredible. Those were interesting times.

I mentioned to you that Dave Garroway, who had gotten out of the Today show, was doing a number of specials. He was one of the guys who developed “speech view”, like when you see someone at a public speaking event looking into a piece of one-way glass. These are outrigger prompters so that the person can keep eye contact with the audience but he’s literally reading his speech off of this glass. This same piece of glass was designed to go over the lens of the camera so that you, as the person on camera, would be looking right into the lens but you’re seeing your speech. This was the speech view concept that TelePrompTer developed.

Garroway called me in this one day and said, “Your damn machine has got straight glass.” I mean it was a piece of glass that covered the front of the lens. He wanted us to bend this glass so that when you’re on the side of the camera, you’re able to see it from any angle. I’ll never forget the man saying, “Well you dummy, don’t you understand that glass is the most flexible thing?” I’m sitting there saying, “Oh yeah, try and see what happens when you bend it. It’ll break.” But he was always after TelePrompTer to come up with a revised, improved type of machine so that he could see that script from any angle in the studio. I did the prompting for about a year when Irving had a very large interest in big screen theatre television. We did fights. We did automobile races.

SMITH: You say you did them? Would you make that a little more clear?

READ: In terms of other services that TelePrompTer Corporation provided besides prompting, there was a very large staging operation involving a number of industrial type shows, whether it was just speakers or just musical productions, they were done by TelePrompTer staging people. This also developed into using projection television. GPL–General Precision Laboratory–was the name of one of the early projections. We always had, again, one of these things trying to make 1950 equipment look like it was in the ’90’s. It was tough. You had tough screens. When it was good it was very, very good. But if it had a little kink in it, it could be lousy. TelePrompTer was doing closed circuit fights. More and more companies were interested in making presentations that were available around the country that you could send out to people as opposed to bringing them all to New York or Los Angeles. You could do a meeting and deliver it via television to these different areas.

Irving recognized the fact that, in those days, the leading motel keeper was a chain called Holiday Inn. That was the major player on the market. Irving hired a gentleman by the name of Bill Sergeant, who had been a vice president at NBC. Sergeant had some kind of connection with this Holiday Inn chain and he put together a staging package where every Holiday Inn across the country was going to have a moving, portable, large-screen projection unit for slide presentations; front screen, rear screen. There was a very special projector that Hub Schlafly had designed. The Telepro 6000. It was special because it could take a screen and light it up in daylight and project information on the screen. You didn’t have to sit in a darkened room. All of this equipment came together as an audio-visual package for Holiday Inn. It also had built into it that, if the need arose, you could put in television. That’s the area that we were moving–more and more video.

It was through this Bill Sergeant that I had gotten involved in a conversation one day. He was asking me about some of the different shows that I had been involved with. He said, “You ought to know something about this thing called CATV.” I said, “What’s that?” He said, “We’ll know more about it pretty soon because we’re about to buy a system in Elmira, New York.” I said, “Where’s that?” I had gone to school in Syracuse and I, on a couple of occasions, had been known to wander down to the SAE house down at Cornell. They had pretty good parties there. I remember seeing the sign Elmira. Never been there. That all came back to me. Lo and behold–this was now into the ’60s–it was just at this time that Irving had decided that CATV was the area in which he wanted to expand and grow because of this closed circuit ability. He acquired systems in Liberal, Kansas; Farmington, New Mexico; Rawlings, Wyoming and this was, of course, miles and miles away from little old New York.

SMITH: Did he acquire the Elmira system?

READ: He acquired the Elmira system because it was “in his backyard” and he could show it off to people. He wanted people to see what CATV was all about. The system that he acquired–it was very, very interesting because there were a couple of firsts. Spencer Kennedy Labs, Boston, Massachusetts had designed a very special amplifier in those days. It was a broadband, twelve-channel amplifier.

SMITH: What roughly was “those days” in terms of year?

READ: This would have been 1956 or 1957. They had gotten involved with a local TV repairman in Elmira and put this brand new concept of amplifier in. Before, they were called strip amps where you have an amp for each channel. That was what you put in back in the very, very early Jerrold days. The local operator got into trouble and they acquired another fellow so then there were two local repairmen. They had sold the system to a company called the New York Water Board. The New York Water Board ran water companies in New York state. It was interesting because they, I guess, felt that this was like running a water system. Their attitude was they would not build an inch of cable down the street unless everybody took the service. As we know, cable even at this day when we’re forty years along, we still don’t have one hundred percent penetration. There are still a few folks out there who will admit that, “I don’t even own a television set.” There are still a few folks out there that don’t have cable.

Well, this was one thing that was absolutely mind boggling that they thought they could build a cable system like a water plant. That they’d run it down there and everybody would take it. So it was at that point where the system was acquired by TelePrompTer. Great local problems, great bad press. It was the end of ’60 when this came about, when the negotiations were on. I believe it was February of 1961 when I got a call from a gentleman by the name of Monroe Rifkin, who was the treasurer, at that time, of TelePrompTer Corporation. He later became the founder of ATC. Today, he is still in the business as Rifkin Associates. Monty said, “I understand you might be the guy I should take up to Elmira with me to look at this cable TV system.” This came about from a comment of Bill Sergeant in a meeting that, “You ought to take this guy up there with you.” So I said, “Sure how do we get there?” He said, “There’s a train.” Trains were still around but it was the Phoebe Snow train of the Erie-Lackawanna that left from Hoboken at midnight. We met and got on that train and we even had one of those pull-down beds. We each had a compartment. We chugged into Elmira at 8:00 in the morning.

The other thing that I’ve never forgotten was the twenty-six inches of snow on the ground. We had something that was brand new in those days called an attaché case–a nice leather box with a handle on it. As they used to lovingly say, that would keep the sandwiches flat and fresh. In those days, it wasn’t too uncool to wear a hat, even one of the better stetsons around. We stepped off the Phoebe Snow in Elmira, New York and looked around and had to call out for a cab because there weren’t any cabs waiting. We took a cab over to Elmira Video. The office was located on 156 Lake Street and it was part of an old piano store. The owner’s name was Claude Buckpitt, who was one of those gentlemen who had the starched collar.

We walked into this store. The pianos were on one side and over on the other side there was a counter with the old swinging gate. The one thing that you noted right away was that there were these very small black and white tiles all over the floor. And you said, “Gee whiz, I wonder what this was?” It was the old building that used to be the movie theatre in the early, early days of Elmira history. That was the old men’s room we were standing in which was part of the office now. I looked around and said, “What are we doing here?” We asked for the manager of the firm, Elmira Video, and these people looked at us and said, “He’s not here.” We said, “Do you expect him in?” They said, “We don’t know.” As we later found out, because we had to sit and wait a little bit, the manager had left two days before in the middle of the night and just kept on driving out of town.

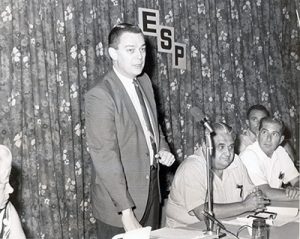

We had to sit and wait for somebody from the bank to come over and tell these people that the company had been sold. Those people–there were three ladies in the front office at that particular time–had no inkling that this was going on. In we walked with our hats on and our attaché cases ready to enter into the world of cable TV. That was my introduction to CATV in Elmira, New York.

SMITH: And it had been sold to TelePrompTer?

READ: It had been sold to TelePrompTer, yes. That was my entry into cable. I was there for a couple of weeks to look this operation over. A year and a half later I was still there. I kind of got hooked on Elmira. I was the first manager there on-site. It was one of those learning experiences because you really had nobody to tell you how anything was done but you just kept asking a lot of questions. I did find that the local people had never been told anything and were just plain upset with cable. Cable was a dirty word to start chomping on somebody.

The thing I found was that no matter what you were going to say or do, you had to let them get it out of their system and go ahead and beat up on me, and then kind of say, gee, here’s a break. Now can I tell you what we’re going to do. It didn’t take too very long before we had a quick, fast program to do things like basically improve what we had, which wasn’t very good. The system had been neglected. There had been no money put into it. The SKL amplifiers had a row of twelve tubes. In half of the amplifiers the tubes weren’t working. In those days it was $1.50 a tube or whatever and they didn’t have any in stock.

SMITH: These were broadband amplifiers?

READ: Broadband amplifiers, yes.

SMITH: Five channel or three or…

READ: These were twelve. This was one of the very first twelve-channel systems that was in existence. Not working very well, a lot of problems. Again, it got to some very basic things like there was a continuous on-running program of retubing these amplifiers. You constantly had to be retubing. The other interesting thing was, in those days there were things called tube shields. It was a little metal casing that would slip down over the top of the tube. Of course, the technicians used to find this a pain in the butt to have to pull those things and put it back. They’d never put those caps back over the tubes so we had radiation problems. This was something you begin to realize, after a while.

At the same time we were trying to do that, we instituted a program of cleaning up the system. You have to start right at the headend of the beast. It was an interesting situation because the headend was located at the local UHF station. Elmira is a community that is nestled down behind the hills. It’s kind of like a dried up lake bottom. Surrounding–God bless those hills–and keeping the signal out of Binghamton, which was fifty-four miles to the east, and Syracuse which was about sixty-five miles to the north. You have the Pennsylvania border right there. The closest would be Wilkes-Barre – Scranton, which was again UHF stations that had trouble getting signals out. We had the headend actually located in Channel 18 WSYE, a spin-off of WSYR, which was Channel 3 in Syracuse. This was kind of a, oh yeah, we got coverage down there through the other little UHF…

SMITH: Translators?

READ: It was a step up from translators because they had a studio. They would originate one show a morning. They did the local cutaways during the Today Show, that kind of thing. The lady’s name was Near. She used to run an information show, What’s Going On In Elmira? It was very unique that here we are competing with this UHF station who hated our guts, and yet and we were in their transmitter site with our headend and our equipment. We also had a great amount of problems because of the radiation of the station’s signal. Their signal was so hot that you constantly had to be fighting that problem. The relationship went on.

Of course WSYR was owned by the Newhouse organization. They had been looking at cable TV. Their company in that area is called New Channels. They had expanded and started to grow in areas like Corning, New York.

SMITH: Could I interrupt just a minute Les and ask you how many channels were you actually delivering in Elmira when you went in to take over that operation?

READ: It was a twelve-channel system. I think we might have had about six or seven channels, which wasn’t very good. We had serious problems when we walked in there. It was also a very small area, in fact, it was two thousand homes that were being served. We weren’t sure where they all were. We had trouble trying to figure out where the accounts were or when they last paid. I mean, basic business problems like you can’t imagine. It was a nightmare. All these things came at the same time where you had to try to put the pieces together.

As I said, we started at the headend and started cleaning up the lines. We knew that we had to do something to show some growth in the area. In one of the early meetings or press conferences that we held, we said that we were going to start at the closest area to the headend and we were going to build that section. That was more out towards west Elmira, as I remember. We had all these problems going on at the same time. This was my comment to you before about the fact that people just wanted to kick you up the side of the head because no matter what you said or did, cable was no good and you were cable; and that is who they wanted to kick. It was that matter of letting them get it out of their system and sitting and listening to them. You had to listen to those people.

SMITH: You’re big enough that you didn’t need a bodyguard.

READ: That’s right. I got into some uncomfortable situations. One of the nice things while I was there in Elmira was that two doors down from the Elmira Video office there was a local bar and grill called Sykes. There were three brothers. Arthur, who was a boxer and once went in the ring against Joe Lewis. There was Bill, who stuttered a lot because he was nervous, with his other two brothers. He was kind of the manager. And there was Ferris Sykes. Ferris was a wrestler, a gargantuan wrestler. They ran this very colorful local bar and grill. In those days it was my McDonalds. I could walk in and grab a burger. There was a woman in there who was like having a mother away from home. She was always telling me that I had to try this today or try that. I would usually eat two meals a day in there at least. I had an apartment in town, but it was not equipped to cook at all.

SMITH: This was before you were married?

READ: This was well before I was married. The interesting thing was that I didn’t realize who all the players were that came into Sykes Grill. Elmira is in the county of Chemung and is the county seat. You had a county government going on and you had a city government. Down on the corner was the Town Hall where the Mayor and the City Manager were. I didn’t know who all the players were but they all came to Sykes too. It was after about three months I started to put names together with what I read in the paper. The only guy I had met, at that point, was the General Manager of New York Telephone Company, who had no time whatsoever for cable television. He just didn’t like us at all.

SMITH: Were you on his poles?

READ: We were on his poles. New York Tel and New York State Gas and Electric. You know well the history of pole attachments in the early days. One of my challenges in life was that after having taken this beating of being associated with cable, I had to prove I’m not a bad guy just because I’m with cable. Whenever you went to any community function, the General Manager of New York Tel was sitting at the head table. That was one of my goals and objectives in the early days to say, hey, there’s nothing wrong with cable and I’m going to be up at that head table. Eventually, I got there. I used to love to give him a little shot in the ribs to say you’re not the only guy in town.

We went through this period of learning who all the players were. We were constantly getting killed by the press. Every story would come out as a major happening of something screwing up. And yet, the press was always there saying don’t you want an ad. So it was a rather unique relationship. Again, I might add, that the whole paper staff, the reporters, Coe Hoover, the editor, they also ended up over at Sykes Grill. That was the place to be. That relationship continued to grow. I must say that after we got through all the horror stories that they had to play they started to turn around and say yeah, but cable is doing that or here’s… and they would carry some of our stories.

It was about three months into my existence there–I would commute back and forth on weekends wherever I could because in those days I had an apartment with a buddy of mine who I grew up with, at 38th Street and Park Avenue, not too far from here, which is a very nice neighborhood. It was the old silk stocking district, as it’s called in Manhattan. A beautiful apartment, rent-controlled apartment. Even in those days it was $150.00 a month we were spending in rent for an apartment that had a front door and a back door and elevator service and a doorman and everything. Here I am in Elmira saying, “Gee, that’s the place to be.” In those days I always had a soft spot in my heart for hard-working women like stewardi, as I lovingly called them. We were in that area where the buses were running back and forth to La Guardia from the Eastside(Eastern?) Airlines terminal. We were always meeting dates. It was a great location all the way around. So I’m sitting there saying, “What am I doing here in Elmira when I should be down there in New York?”

I was always trying to schedule as many meetings as possible because New York is sitting there saying what’s going on up there, what’s going on. Irving had a constant stream of people coming up and going back and forth to Elmira because Elmira was only about an hours’ plane ride away. Of course in those days it was called Mohawk Airlines. When they flew, they were very, very good. Mohawk would bring people in and out of Elmira and Irving was constantly showcasing this system because, as I mentioned to you earlier, the other systems that he first got involved with were way out in Kansas and you couldn’t get to them too easy.

Irving, of course, was trying to introduce CATV to the financial world, to the stock analyst type people, so you were constantly getting visitors wanting to see what this thing was all about. Again, it wasn’t instant visitors because, as I mentioned, we had a lot of problems. You didn’t want to show all your dirty laundry. That whole tide eventually changed. We started to get a little better press coverage.

As I mentioned to you, we wanted to clean up that headend as quickly as possible, but we had to get new equipment to update and bring in state-of-the-art. As that new equipment came in we were always constantly out there trying to get that message across to the people in the community. As I mentioned way back there in the beginning of Side 1, in my days of pumping gas–perpetual gas–it taught me how to deal with those people. It was a service business that we’re in. To this day, thirty some years later, the number one problem that cable has got is service. Of course, it has continued to come back and bite us in the ankle and the nose and a lot of other locations because of the fact that we haven’t always done the very best job of listening to the subscriber, or answering that phone as quickly as we should, and yet what I find absolutely amazing is that not too many other industries are doing a very good job either. When I go to call a bank, I get music. When I go to call an airline to find out if a flight is coming in or to book a flight, I get music. I get put on hold. It’s just the fact that everybody is using communications so much more hectically and quickly that cable isn’t the only one in the world with these problems.

Elmira started to grow, subscriber wise, and we realized–again, if you take time to listen to Irving’s historical information, I’m sure you’d detect what a dynamic promoter this guy was because he told me the stories when he was first working Skouras in the theatre business where he would get more excited about the popcorn machine and have to sell Skouras on the fact that you’d make a lot more money out of that popcorn machine.

SMITH: He always was a visionary, wasn’t he.

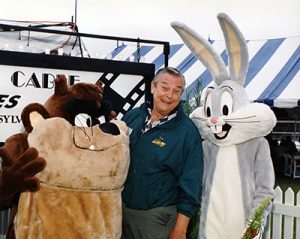

READ: Absolutely right. It was through a lot of those things that we continued to get the message across. As I said to you before, after three – four months at this restaurant, Art Sykes turned around and just kind of started introducing me to the city fathers and say, “This kid’s doing a heck of a job up here.” It was kind of a blessing from Pope Art. Suddenly, you were part of the community. But boy, for that first three to four months, it was very, very lonely there. They would look at you with that New England yeah, you’re there but I don’t know if I like you or not. Yankeeism like you can’t imagine. I had to get through that period in Elmira, New York before the tide finally started to swing. But, I was accepted. Today, I think of Elmira as a second home. I have a number of second homes because my travels throughout the country in cable have given me the opportunity to meet a lot of townspeople, and things of that nature. That was the challenge, to get that x number of city leaders, city fathers, the powers-that-be in that community to say that maybe these guys are all right. They’re not here just to peddle some imaginary deal. It was after that, the numbers started to turn and we started to add some subscribers.

In talking about promotion, the biggest promotion that we did in those days, there was an antenna on so many roofs up there and the mast was sixty feet. The antennas were a couple of different type antennas. You had a UHF antenna and a VHF antenna because people were trying to pull these signals in. This gave us a great opportunity.

When we stop this tape because we’re going to change over, we’ll continue talking about some of the early promotions to get attention in Elmira. That was a fascinating period.

End Tape 1, Side B

SMITH: This is Tape 2, Side 1 of the oral history interview with Les Read in his offices at HBO in New York City. Les, you made some notes about where we should start when we reached the end of the last tape.

READ: We were talking of Elmira, New York having made some headway correcting all of the problems the system had when we took it over. We proceeded to get a bit of a turnaround of the local community feeling towards us and, at this point, started to introduce promotions merchandising to get people to react and either come into the office and place an order or pick up the phone and call in an order. The setting, of course, in the early days of cable was that you would charge $150 for the cable installation and the monthly charge for those seven or eight channels that we were delivering was costing about $3.50. We suddenly said that for $150 we wanted to have a broader appeal; if we could get more people on we could afford to reduce that price and introduce some installation-saving type of fees. I don’t recall being able to ever find any major promotions that had gone on by the other companies that had been involved there. So when we introduced these specials, these promotions and price reductions on the installation, it literally floored an amazing number of people. First off, the people who had paid their $150 to get the cable installed were calling wanting an instant rebate. Here we were back in the hole again trying to find our way out with the existing customers after we’d shown them all the improvement. We made a dramatic announcement in the fact that the installation price would now be $39.95 based on the reaction we got. Once that happened, things started to fall into place. That was a point that we worked from.

One of the most incredible responses that I have witnessed in terms of a promotion was what was called, in those days, an antenna trade-in. As I was mentioning to you on the earlier tape, in Elmira, because we were surrounded by all these hills, if you wanted to bring some signals into the home from Binghamton or Syracuse you really had to have an antenna mast that would reach up thirty, forty, fifty feet. Some people had some very elaborate guide wires on the roof to reach out and grab that signal. We did a number of promotions first introducing $39.95, which was very successful. People said, “Gee, that’s reasonable.” I believe that the early rate, at that point was about $3.50, although we did go to a $4.50 rate shortly after that. After we picked up all those $39.95, then we came up with this idea of an antenna trade-in where people literally just came to the office doors with these antennas hanging off the car, around the car. We had even agreed in the beginning to go up and take the antenna off the roof for a few people. That was until we got into some legal problems where we were threatened with being dragged off to court for ruining someone’s roof. They wanted a new roof job from the cable company. We quickly got out of that. We told them if they delivered the antenna we will give you the credit. We literally went from two thousand very unhappy subscribers–we were probably, more realistically at eighteen hundred–about a year later, we finished at approximately seven thousand five hundred. Not everyone was installed as quickly as we would have liked, but the demand was so great and we had to continue to do a PR program about what area was being wired next. We literally had people standing and waiting for things to happen when it came to cable.

This continued as a very positive growth and, at the same time, there was a whole new development of microwaving signals. We went on the hook for bringing in some New York channels and had agreed to bring in WPIX, WOR Channel 9, WNEW, which today is a Fox network, but was an independent station in those days. When that happened, that literally just mushroomed. This came in probably two years later on. I had gone on to another assignment, which we’ll talk about later, in Montana. This is what blew the growth of the Elmira system, the barn doors right off the place, when we got into these microwave signals. To that point we had improved on the existing signals we were bringing in over the air from surrounding areas such as Scranton, Pennsylvania and Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. We had WBRE Channel 28, which is a David Baltimore station. These are names coming to me thirty-five years later. WNEP TV. We had Binghamton, New York channels. We, of course, brought in Syracuse.

I had left after maybe a year, year and a half. I was reassigned. I got one of those phone calls from Monty Rifkin and he said, “You’ve done such a terrific job.” And I’m saying, “Oh boy, here it is, I can get back to New York to my apartment on Park Avenue.” He said, “We’ve got real serious problems in Great Falls, Montana and we’d like you to go out there.” I was just literally stunned. Great Falls, Montana. I was kind of concerned about cowboys and Indians. That was a far piece out there. It was at a natural point in time when, where we had been and the projects we had going on, I felt comfortable in saying, “Well that’s something to look at. If this is what I have to do to get ahead, let me take a look.” At that, I made a trip out to Great Falls and, indeed, did find Indians.

SMITH: Before you get into Great Falls, Les, I want to interrupt you because at lunch with Irving Kahn you were telling a story that I think occurred at Elmira that I think would be very appropriate for this history.

READ: It’s appropriate in the fact that TelePrompTer Corporation was not afraid to try the new things that the industry continued to bring out. In a lot of cases it was Irving that was forcing them to; if you do this, this, and this, I’ll buy it. Well they’d run back to the drawing board and design and develop. That particular story that we’re talking about really belongs in the second time when I went back to Elmira. When I went back, there was a brand new cable that Times Wire had introduced that was called JT408. It was a brand new method of overlaying the copper braid–it was a very heavy copper shield–that was on this feeder line. In fact, it was so new they had forgotten that they didn’t have any connectors to fit that cable. We had suddenly received miles and miles and miles, and reels and reels and reels of this JT408 cable, which was going to eliminate an amplifier every quarter of a mile. This would really cut down the cost for the operator.

Great strides were being made. But we sat there with the cable in the warehouse yard waiting for Jerrold to deliver. We’d get two at a time. Some of the good days we’d get six connectors in a box for this JT408 cable. The cable got installed. The connectors, as we got them, were put on and suddenly the signal started to disappear. What had happened is that this copper braid started to be affected by the weather. Because of the effect copper has got we started to lose signal in this brand new, rebuilt plant that was the end-all to all the worries and problems that any cable operator could ever have. Fewer amplifiers, put it up and it’s going to operate. What it turned out to be was this corrosion that happened with the copper-clad cable. The only thing we could figure out to do was to have a fellow go out in a truck–this was even before we had bucket trucks–and literally beat the cable with a baseball bat. When the service calls came in, this one fellow who was the chief technician and who has gone on to become one of the brighter technical forces in the industry, Shorty Coryell. Shorty, the last I knew was still with ATC out in the Colorado area. He and his wife Rose have about eight children I think it was. Shorty was one of those hands-on people; very much involved with how to make things work. If it wasn’t there, he’d build it. He was the guy that kept that system running.

SMITH: There were a lot of Shorty Coryell’s in the industry.

READ: This was the early days of cable where, as I have always said, this industry was guinea pigged to death because of technological advancement that was coming based on, gee, if we had this or I got this idea. And someone would run to a breadboard and sit down and–boom–here’s this piece of equipment. Transistors were just coming into being. This wasn’t my first trip to Elmira. When I came back the second time, transistors were just there. The first transistorized system was a Bruce Merrill system, which was where I went next in Great Falls, Montana. Bruce had come out with an Ameco AT60 series. We’ll talk about how that got installed in the middle of the wintertime, 46 below zero. It just didn’t work. Elmira was truly, in those early days, being a guinea pig like any other system across the country. Elmira, it’s interesting to note, became one of the big systems of all times at 23,000 subscribers. At the time, it was the number one large size system in the country, which today, of course, is small when you look at the San Diego’s and the Manhattan’s and the other major markets.

Manhattan was one of the last areas to get cable. Here I’ve been in it for thirty years and I’d come home to see my family and talk about cable and they’d all scratch their heads and say, “Why would you do that? Why would you have that?” Never understanding what cable was all about. And yet, today, it’s a very major force, as we know, even in the metropolitan market.

Elmira went on to grow. I left the system. I had gotten the call. The next manager in was a fellow who’s been around the business for a lot of years and his name was Jack or John Gault, who is one of the senior executive officers at ATC in Stamford, Connecticut now. He picked up and spent about a year or so in Elmira running the system. Then there was another manager that came in after that, a gentleman by the name of Don Guthrie, who was a local salesperson in radio and television. The next thing, I came back from the other assignment and I ended up back in Elmira in 1965 – 1966, for my second tour of duty. Again, there had been this spectacular growth–off the charts, off the wall. I came back and we were running into a few more community relations problems again. The system had grown to such size that I was asked to go back to Elmira since I had a few connections.

SMITH: Sykes Bar and Grill?

READ: Sykes Bar and Grill. It was almost like having a parade when I got back to town. I went back and at this particular point I was married. I had gotten married in October of 1964. To set all the timetables, I had left Elmira in 1962, went to Great Falls, Montana. That was a brand new system that was just starting. It was one of the very first systems that was ever built where there were two VHF stations. In Great Falls, Montana there were two V’s, although they would still get their Christmas shows on Kinescope recording in July. You would watch Christmas shows.

SMITH: Would you prefer to do the Montana story now and then come back to Elmira?

READ: Sure. I was just trying to put all these things…

SMITH: Let’s not forget Shorty Coryell.

READ: Right. Shorty deserves a lot of credit for keeping cable on the air.

SMITH: We want that New York Telephone story too.

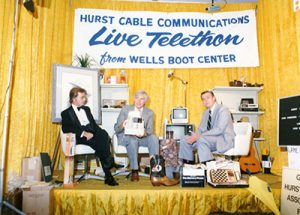

READ: That would be a part of that first visit. In the start-up promotion because of TelePrompTer’s involvement as we talked about the prompting business, the staging business, this whole area of closed circuit television continued to grow to doing projection television of fights, automobile races, trade shows. One of the things that happened was that a major fight, major heavyweight fight between Ingmar Johanssen and Floyd Paterson was being fed across the country in March of ’61. We were able to get a network line into Elmira that we fed to two locations; one to the local theatre and the other to the headend of Elmira Video.

SMITH: Where did the fight originate?

READ: I would have to double check. I’m not sure. The key thing was that, again, part of this promotion of being new in town, we said that if you would sign up for Elmira Video service–again, this was at this new $39.95 rate–you would get two tickets to the theatre as a special premium. It was a very, very successful promotion. We also put tickets on sale and brought busloads of people from Binghamton, New York which was one of the large sports capitals of upstate New York. There were just so many sportsmen. They’re crazy for fights, wrestling and all that. They drove over. There were caravans of cars coming in from Binghamton, New York. People came from Syracuse and all the surrounding areas to see this championship fight at the theatre. At the same time, we made this signal available at the headend, and then proceeded to say we were going to put it on the cable system. The first reaction we got was from New York Telephone Company saying, “No you’re not. You cannot do that. You have a pole contract that says no pay TV programming will be carried on those poles.”

SMITH: Those provisions were not uncommon in those days.

READ: Exactly. In fact, there are franchises out there today that still have that.

The key thing was that we had broken the story. Again, in building this relationship, the community and the paper treated us very well. The local sports guy, who was a good cable fan, writes this magnificent story about, wow here’s 1960 and Elmira is living in the year 2000 already, to think that we were going to get a championship fight. My immediate reaction was that we need to let the people know, because again we had talked about this promotion that we were going to do. We ran an ad. There are some claims that there are some copies around. We’ll have to do some research and see what we can find in Irving’s attic or my attic. It said that we would like very much to bring this fight to you but, unfortunately, the New York Telephone Company says we can’t do that. I guess that you could buy two editions to the paper in Elmira. There was a morning paper and an evening paper in the good old days of publishing. It broke in that morning paper. All hell broke loose because my phone rings at home. I was not–maybe just one foot–out of bed when Irving Kahn calls from New York saying, “I don’t know what the heck you’ve gone and done but whatever it is, cancel it, pull it, get it out of the paper,” because it started all sorts of calls going into the phone company.

SMITH: The ad said that it’s the telephone company’s fault? They won’t let us do it.

READ: That’s right. It said that we would do it but they weren’t going to let us do it. We were trying, again, to be the good guys and try to do something for the community. Having gotten this call and, knowing the forceful type individual that Mr. Kahn is, believe me, I pulled that ad pretty quick. Lo and behold, I had a letter hand-delivered over to my desk that said, “Based on the unique situation this would be a one-time only test project.” We were going to be permitted to carry that fight, which we did.

SMITH: The letter was from New York Telephone Company’s local office.

READ: The local General Manager of New York Telephone.

SMITH: How was Mr. Kahn brought into the picture?

READ: His phone started to ring, I’m not quite sure how early because I know mine was ringing between 7:00 and 8:00 a.m. in the morning. The paper goes to bed at night, I guess. I never had the total story from the newspaper people but based on that ad they started calling the General Manager in the middle of the night saying, “What are you doing about this? Why won’t you let the town…” It also brought New York Tel’s home office here in New York City into it; how do we respond to this threat and this problem. Irving had calls during the night from New York Tel’s main office. Based on them saying they were going to let us carry it, he’d called me to say get that ad out of there. We’ve accomplished what we needed to do. We carried the fight and it was one of those–I don’t want to say like a carnival come to town–pretty exciting. We had lines of people standing out in front of the movie theatre, which they had not seen in Elmira in quite a few years.

We had one slight problem in the fact that the projection unit, the GPL television projector that we were talking about that was the first model to provide big-screen television, kind of fell off the truck a little bit. It wasn’t a far fall but there was a fall. There was a little bit of damage.

What had happened to us is that in the early days of television when you had three people looking at a screen, each one has a different idea of what that screen should look like. Everybody’s eyes adjust differently. So that we damn near had a riot on our hands at the theatre from those people who had come all the way from Binghamton and surrounding communities and from those people who had bought their cable promotion and had gotten their two free tickets. It was a big, old theatre. I’m not sure if it held three hundred or four hundred people. But it was a pretty good size theatre for Elmira. We had ourselves quite a ruckus because the shouts started–fix the contrast, brighten the picture.

A large group of folks seemed to have brought in their own refreshments and there were a few beer cans that started rolling down the aisle. We had a young man who was a PR type person from New York, George Eskin. George was a young fellow just out of school and extremely nervous. He had the theatre assignment to make sure everything was going all right over there. As we lovingly said, the last we knew, we saw him driving out of town, just after the fight started, in his little Volkswagen Bug with people shouting after him the whole way.

It was quite a hairy time getting that fight on that night. It gave such an incredible amount of attention to the cable, credibility to the cable, that they could do something like that. We took our kicks. We were blamed for lousy pictures, and this didn’t work right and that didn’t work right. But, they did see the fight. We came back to them and said, “But you did see it.” In those days, they were a little bit longer than two-minute fights that we’re used to in the ’90s and the late ’80s that Mr. Tyson puts on. It was a slugfest, as I remember. It went for quite a few rounds. I think, out of the whole theatre, there were maybe three people who came and asked for their money back. You get very nervous when you have to face three people but we could’ve had to face a lot more than that. After all the dust had settled, we said that was probably one of the most effective promotions. It got our name on the map. We showed the community of Elmira that TelePrompTer/Elmira Video was capable of doing something.

It was based on that kind of event throughout all the years I’ve been involved, as I stop and think about all of the different services–I was involved with one of the first weather machines in Great Falls, Montana with a company called Telemation run by Lyle Keys. Lyle had this neat little camera that would go back and forth. I was able to talk to Pacific Northwest–I’m getting way ahead of myself on this one. We brought all the cable operators into Great Falls, Montana, which was a new system and we showed them at the same time this new Telemation unit. It was the first one operating on that system.