Interview Date: December 06, 2007

Interviewer: Steve Nelson

Collection: Cable Mavericks Collection

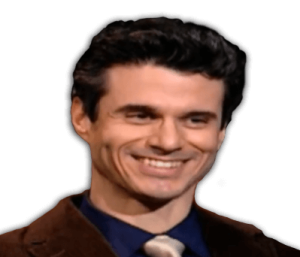

NELSON: Hello, I’m Steve Nelson for the Oral and Video History Program of The Cable Center. Today is December 6th and our guest is Evan Shapiro, General Manager of IFC. Evan, welcome.

SHAPIRO: Thank you.

NELSON: I’d just like to start, as we do with these things, go back to your childhood. Where did you come from? Tell us a little bit about growing up.

SHAPIRO: I didn’t think you were going that far back!

NELSON: We go all the way back.

SHAPIRO: I grew up in south Jersey, a place called Vineland, New Jersey, and then Cherry Hill, New Jersey, and Cherry Hill is right outside the Philadelphia area. I come from down there, which is why I pronounce my name SHA-PY-RO.

NELSON: Is that a Philly thing?

SHAPIRO: It is a Philly thing. They pronounce things weirdly and they have losing football teams. But it was a great upbringing and specifically growing up in Cherry Hill I went to a great high school, a great public high school down there, and the communications department and the theater department down there taught me a great deal about storytelling and doing theatrical productions and technical things and design that I don’t know that a lot of kids in this country get a chance to experience, especially with drama programs being ripped out of schools more often than not these days.

NELSON: Certainly not at the high school level. That’s kind of unusual.

SHAPIRO: Right, and the high school had, at the time, the largest auditorium in the state of New Jersey so they used to shoot all of the Miss New Jersey pageants there and produce the Miss Jersey pageants there, so I met successive Miss New Jerseys and I got to work backstage at a lot of these things and I was in a lot of shows and I got to direct some theater while I was there and went on a tour with a theatrical production to Hawaii in an exchange program which was really nice. So I learned a lot about show business and I actually at one point would go door-to-door knocking on businesses doors selling advertising for the playbills to help us support the shows themselves.

NELSON: While you were still in high school?

SHAPIRO: Yeah, because they were high school theatrical productions and I did a lot of community theater down there. So the community that I was able to become a part of in the theater programs down in south Jersey and the love of theater that my parents gave me, and my addiction to television really was very important in influencing me on where I went with my career as things rolled out.

NELSON: Talk about that addiction. Most people don’t speak of that at such a young age.

SHAPIRO: I was of the generation… Gen X is a very small generation but there are a number of different kind of oddities that happened with the Gen X crowd – the first latchkey kids, the first generation raised on Sesame Street, and Sesame Street was the first time that television was proven to be educational, or at least there was a major attempt for it to be actually educational but at the same time entertaining. So to be raised on that and those types of things, at the same time gaining an actual addiction to Tom and Jerry cartoons and Warner Bros. cartoons – all the jazz I’ve ever learned, or most of the jazz I learned early on and the classical music I learned all came through Warner Bros. cartoons and Hanna Barbara cartoons, and that grew into a larger appreciation of pretty much any television. I would watch – good, bad or indifferent. I had a great time watching fluff on TV, but at the same time when you grow up watching things like M.A.S.H. and Nicholas Nickleby on television, which because of the merging of theater and television – I was in high school at the time – that was a pseudo-religious experience for me. The idea that over a couple of nights you could do a live theatrical performance that felt personal at the same time was really something that influenced me a great deal and I know a lot of people in the television business consider Brandon Tartikoff as a hero, most of those people were lucky enough to work with him or at least know him or at least be in the business when he was in the business. I was probably one of the only kids in south Jersey who used to follow his career from high school and junior high. So I was a big addict, I always wanted to work in television. I went through theater as kind of the easiest way for me to get involved in entertainment, but it was the collective experience of watching things on television as a young person that really informed a great deal of who I am now, and the idea of television as a powerful educational device, but also a powerful cultural device – watching things happen like elections and World Series games and the last episode of All in the Family, and having those collective, universal experiences, which are harder to have now with the fragmentation of television and the cable and the internet and those things kind of invading the space and creating a little bit less of a universal experience, but it did teach me or prove to me that you can have a great deal of import in the world using things that are every day to some folks.

NELSON: You mentioned Nicholas Nickleby, which kind of struck me because you’re talking obviously about one of the great storytellers of all time…

SHAPIRO: Dickens.

NELSON: Dickens. So was that an influence on you in terms of using this medium to tell a story?

SHAPIRO: Yeah, absolutely. We did Trapped in a Closet on our website this past summer which is a hip-hopera, an online only series from R. Kelly, and the way we rolled it out was very Dickensian, and the story itself is actually pretty Dickensian in a kind of weird sort of way. But he was syndicated. He was a syndicated, episodic storyteller. He would write a book, in chapters, and roll them out in a newspaper or magazine week after week or month after month, and that’s how people consumed them. The novels would be bound and sold later but…

NELSON: It was a series.

SHAPIRO: Oh, yeah, it was a series, and he was one of the most commercial writers in his time that we’ve ever known, and the idea that you can actually serialize and keep people… they don’t have to necessarily read it start to finish in one sitting, that people can stay tuned in. So, yeah, and the idea that that piece of theater was told, I think over four nights on television, there’s a lot to that and a lot to his storytelling capabilities that I think when you see things work well on TV or in film today there are still a lot of those things being employed. When you see things failing, they forget the very nature of storytelling and character development and making characters in stories relatable to the audience that you’re trying to distribute them to. So often you’ll run into an artist who’s got a great idea for a show or a film or a documentary, and my first question to them is who is this for? Well, it’s for short, brown-eyed people named Charlie in Texas. Well, that’s not a very large audience, but if it’s for young men how are we going to get it to them? And more often today understanding not only who it’s for but how that audience will now consume that piece of content – how are these people going to watch this television show? Are they truly going to watch it at 9:00 on a Thursday night or are they going to put it on an IPod and walk to school with it? And while I am a big believer on how stories unfold naturally and organically, oftentimes you find artists not necessarily always understanding who their story is for and how best to reach them. So if I’ve had any level of success in my career it’s been finding pieces of art and understanding how to get them to the people who want to see them or read them or watch them.

NELSON: Well, let’s go back before your career a little bit…

SHAPIRO: Sorry.

NELSON: No, no, that was very good, and it showed the influence of Dickens all the way through to today.

SHAPIRO: Yeah, every day still.

NELSON: I’m a Dickens lover myself so I couldn’t let that one go by. But you got out of this fabulous high school. College?

SHAPIRO: Well, I went to college. I was at the University of Massachusetts which is in Amherst, Massachusetts and I became a political science major because my parents wanted me to go into law.

NELSON: A common ambition for parents, anyway.

SHAPIRO: Especially for Jewish parents from south Jersey. So I went to school, I did not have any desire to be an attorney, and I got involved in a student-run theater organization at U-Mass, which had been in existence for about 50 years, called the U-Mass Music Theater Guild. It was dormant when I got there and a bunch of us started it up from scratch and produced theater from scratch employing a lot of things I had learned in high school, so knocking on doors, selling ads in playbill to help fund the play, picking things that were a little bit more populist. There was a theater department at U-Mass that was doing very esoteric things that were not terribly accessible – again, who’s it for? But we did musicals and plays that were a little bit more populist.

NELSON: Give me an example.

SHAPIRO: Kiss Me Kate, Company, we did Little Shop of Horrors. I got to direct and produce and market all of these things. The good news was that they were very successful, very well-reviewed, we sold a lot of tickets. The organization built up some coffers and things like that. The bad news is that it wasn’t part of my studies, and so I was doing more and more theater and going to fewer and fewer classes to the point where I actually figured out I had spent so much time and energy on this one thing I decided that classes were no longer something that I needed so I actually dropped out of school much to my parents’ chagrin, and embarked on a cross-country drive to Los Angeles to make my way in television and movies.

NELSON: So you just set out for Hollywood?

SHAPIRO: Um-hmm. Yeah, I dropped right out. This is like therapy! So I drove across country and it did not go so well in California. So I came back and was living with my parents.

NELSON: You’re just out there, some ex-college kid who’d put on some college productions…

SHAPIRO: I’m going to take on the world! Yeah. Again, the south Jersey equivalent of that young girl getting off a bus in Times Square with a suitcase in her hand, I was that kid only male and in Los Angeles and it did not work out in kind of a very overwhelming way. So I was back in my parents’ house teaching school – not teaching school because I didn’t have a degree, but working in a nursery school, basically – working in a restaurant. I met my future wife waiting tables in a restaurant in south Jersey and someone very smart said to me, “You were pretty dramatic about how you wanted to pursue this and here you are in south Jersey trying to make it in show business.” Not a lot of show business in south Jersey, other than the Miss New Jersey pageant. And so they said, “If you want to make it in this business you have to go to New York,” and so I did. I came to New York…

NELSON: What year is this?

SHAPIRO: This is ‘9-…

NELSON: We always like to keep this chronology going here.

SHAPIRO: This is in 1990-1991, and the city was not in good shape back then.

NELSON: No, that’s why we have to have these dates so there’s a context.

SHAPIRO: It was a really weird time in the city. I won’t get into whose fault that was but I came here, actually got a waiting job, waiting tables in a restaurant, never showed up for it because the day I was supposed to show up I got a job at a modern dance company as a company manager.

NELSON: So you’d been applying for jobs, obviously.

SHAPIRO: I had been banging on doors. I made $15,000 a year.

NELSON: You were good at banging on doors from your ad sales, right?

SHAPIRO: It’s what I do. Since I was 12 years old, apart from school, I’ve never not had a job. So, paper boy, mowing lawns, working at gas stations – I’ve never not had a job, which is, I think, some kind of pathology that I have that I inherited from my grandparents who were babies of The Depression. So I had a job but that didn’t satisfy me so I found another job and I was working in nonprofit modern dance which is nonprofit.

NELSON: $15,000 a year.

SHAPIRO: $15,000 a year.

NELSON: In New York!

SHAPIRO: And to me that was a fortune, by the way.

NELSON: Yeah, but nonetheless you were living in New York City.

SHAPIRO: Yeah, but in New York at the time…

NELSON: It wasn’t too bad.

SHAPIRO: No, because the real estate economy had cratered so I was paying $300 a month in rent. Now it was an apartment out in not a nice part of Brooklyn but I was working in the Village, the commute was easy, it was great. Looking back on it, I was miserable at the time sort of thinking how could I ever live on this, but I was doing this during the day working with dancers who happened to be… the female dancers were incredibly attractive and in awesome shape, so that was nice for a young man at the time, and I met a lot of people and I learned a lot about managing nonprofit arts organizations.

NELSON: In which you obviously had no background in.

SHAPIRO: Other than doing it in college, right.

NELSON: In college, yeah.

SHAPIRO: But I did know marketing and I did know sales, just by virtue of the fact that I was forced to learn it, and so my job was to sell week-long stays for the dance company at universities, so they would come in and do master classes inside the art schools and then perform at night. It was a lot of fun and I got to know a lot of people. It was not where I wanted to go with my career but it taught me a lot. And I directed plays at night in the Village.

NELSON: Were these more experimental?

SHAPIRO: A little bit, yeah. We did a play called The Insanity of Mary Girard, which is about the wife of Stephen Girard who was actually a Philadelphia millionaire in the colonial age who imprisoned his wife in an insane asylum and it’s her kind of slowly going insane. So, yeah, it was a little bit less commercial but for the East Village that’s actually kind of commercial. We aren’t spitting at the audience! It’s like a Broadway show. So it was really eye-opening and I learned a lot, and again, it was pretty successful and I really enjoyed it. And I went through a series of jobs in the nonprofit and for-profit but off-Broadway arts community in New York during the day. I was doing marketing for Penn & Teller on Broadway at one point, was a successive job. I worked on a show called Song of Singapore which was at Irving Plaza, which is now called Irving Plaza – a lot of different theater jobs and then during the summer I would go off and do summer stock. So I still had this yin and yang, primarily in marketing. This is where I first started working in the cable industry, so I got to know the Time Warner affiliate here pretty well – Neil Dash was the head of marketing services there at the time and we did a lot of promotions together. So those parallel tracks went on for a number of years and I worked then at an advertising agency that worked in only commercial Broadway theater, and again, I learned media buying and advertising in a truer sense, and direct mail, direct marketing, and then a job opened up at the New York Shakespeare Festival, the Public Theater, it’s the same organization. Joe Papp had died and someone else had been in theater, hadn’t been successful, and George Wolfe, who had just won a Tony Award for Angels in America, had taken over the Theater, and he and I were introduced and despite the fact that I really had not enough experience to get the job, he gave me the job as the first marketing director in the history of the New York Shakespeare Festival. Joe Papp had been the marketing director up until that point and when he died no one was there to kind of pick up the mantel. George was clearly the artistic director and the producer and he gave me this job at 26 that I didn’t deserve, but he liked me and the way that he kind of reinvigorated the theater gave me a tremendous amount of inspiration to create marketing campaigns and re-brand the New York Shakespeare Festival – Shakespeare in the Park. We did a campaign called Free Will which is a quintuple entendre, and that was really successful. Then we did Bring in ‘Da Noise, Bring in ‘Da Funk on Broadway, and through that I got to work with Christina Norman who was the head of creative services at MTV at the time.

NELSON: Now how did that come about from the…?

SHAPIRO: The board of the Public Theater had a lot of great people from MTV – Bob Pittman and a whole bunch of other people were on the board – so there was an introduction made. Savion Glover, who’s one of the creators and star of Bring in ‘Da Noise, Bring in ‘Da Funk, was the star of this series of interstitials which was a new word at the time – this was in ’95? ’94, sorry. We shot these things at BAM on a bare stage with Savion Glover and Christina Norman and myself. I just watched the television production happen and it just became something I was even more in love with afterwards than I was before and I knew that I needed to make that transition at some point. From there Noise, Funk was incredibly successful. It raised my profile in the Broadway community tremendously. So I became one of the better known marketers in Broadway theater, which was great but not the pinnacle of the career that I was actually looking for, to be honest with you. It was fun and I love theater but theater people are crazy because the idea that you will take money and put it into a theatrical production hoping to see any of it back is just insane. It never happens.

NELSON: Not a very good business judgment.

SHAPIRO: It’s like the restaurant business. So I opened my own shop, and in the theater business I had made a name for myself which was really nice and so I took on pretty much every Broadway production that there was over a two year period and became a marketing agency for those. The company was called Forefront, I opened it with a couple of partners, and we worked on Freak and Bring in ‘Da Noise, Bring in ‘Da Funk, and Rent and Chicago and Lion King and Beauty and the Beast and all the… It was great, but not terribly profitable. So we started to get into the television business and the movie business and the record business.

NELSON: From a marketing standpoint?

SHAPIRO: Um-hmm. Branding, advertising, marketing. A&E became a client, HBO and Cinemax became a client, Universal Studios became a client, and a lot of internet clients.

NELSON: So, you’re getting closer to these TV guys here.

SHAPIRO: Yeah, and now, as anyone will tell you, when you work at a company you’re an idiot, when you’re a consultant you’re a genius. So I was able to walk in and be very pithy and say things in meetings because you’re a paid consultant and you’re expected to be that creative guy.

NELSON: I suppose a little bit of drama, too, given your background.

SHAPIRO: Yeah! And we would do things for clients that were… we prided ourselves on being storytellers first. Again, that was something that was reinforced by working with George Wolfe at the Public Theater. Noise, Funk worked as a campaign because what we did was we took the story of Noise, Funk and put it out there. We didn’t try to gloss over it and “hide the weenie” as they say in marketing all the time. We put the weenie out there and we marketed the hell out of it for what it was. I remember George saying to me, “The name of the show is Bring in ‘Da Noise, Bring in ‘Da Funk’,” and I said, “I’ve got to go sell that to Broadway audiences who are overwhelmingly white and from Westchester? That’s not an easy sell, can we change the name?” No, that’s what the show is. And we put it out there really without apology, and soon after that, a year and a half later, Madeleine Albright was saying we need to bring in ‘da noise, bring in ‘da funk in our foreign policy, and Ellen DeGeneres was quoting it on the Tony Awards and it became a part of the popular vernacular in a way that I had never thought that that type of entertainment could, and it taught me a great deal. Also, to be honest with you, being one of the only white people I know to have had a black boss and to work with an overwhelmingly diverse staff at the Public Theater was really eye-opening because I came from an overwhelmingly white suburb in south Jersey, most of the people that I worked with were of the same ilk, and that diversity of voice not only became very influential to me but it also proved to me that diversity of voice and differentiation of voice is vital to success. So when I worked for all these other producers I always brought that let’s take what’s great about the art and put it out there instead of trying to gloss over it. What’s the best thing about this product and how do we articulate that in a story that people are going to find engaging? It was really successful, it worked really well. The company grew tremendously fast from 3 employees to about 20 employees by the end, and from one office in New York to two offices, one in LA, and it was wonderful. What I realized more often than not though was I missed being a part of a brand. I was really proud of the Public Theater because it was a part of me and I was a part of it. My company was pretty successful and I enjoyed it but it was not necessarily changing the world, it was not necessarily adding something to the world at large. The opportunity to go to Court TV, who was a client at the time, was the fulfillment of a lifetime dream. They basically created a job there for me to re-brand the network and I was working for great people – Art Bell and Henry Schleiff and Dan Levinson – and it was my first television job, and what they liked about me, when I interviewed with Henry… so many stories!

NELSON: That’s what we’re here for.

SHAPIRO: Yeah, I know, but about Henry Schleiff, which he would be very happy about. When I interviewed with him, the fact that I didn’t graduate from college and that I had made my own way was what he liked about me. He liked the fact that I was different, that I brought something different to the table, whereas my inclination probably in the first couple of years in New York was to hide the fact that I had not graduated from college. I tried to be the same. But what George taught me and what my experience in running my own company taught me was that being different actually is good. People like different. Not everybody, but it certainly helps you stand out.

NELSON: You can use it to market from, right?

SHAPIRO: It’s usually the thing you do. “We’re better, we’re best, we’re number one.” Well, why? Because having a differentiation is… what’s the unique selling proposition? So he interviewed four or five candidates for a job that all had kind of similar backgrounds and instead Art Bell and Henry Schleiff were, I guess, courageous enough to give a job to somebody who had never worked in television before, who had no college degree, there was no reason to think I would be successful, but because I brought something new to the table they thought this could work. For that I’ll be forever grateful to both of them for.

NELSON: What was the job?

SHAPIRO: They had a head of marketing in Dan Levinson who had taken them to a point where they were basically almost fully distributed. So the role was changing from one of B to B marketing to a B to C, much more of a consumer thing, and they wanted somebody who could differentiate the network on television aside from the fact that they had trials during the day because that’s not what they were playing in primetime. So I was able to come in and they asked me to concentrate on branding the network and creating a kind of younger, different kind of brand. The word forensics kept coming through on our research over and over and over again. I, frankly before I started working there, barely knew what forensics was, but what the research demonstrated was that probably somewhere around 70-80% of television audiences in general knew the word forensics. They actually used it unsolicited. “What are you interested in?” “I’m interested in crime and investigation – forensics.” That was fascinating to me.

NELSON: That’s remarkable. Did they pick that up from TV?

SHAPIRO: Well, you have to remember, Quincy was a very popular show many years before this happened. O.J. had been on Court TV and forensic scientists had been testifying. Television had taught people the importance of forensics, and in fact, Court TV had a show called Forensics Files on, CSI was in development by Jerry Bruckheimer at that time. So I also knew that forensics because CBS was going to get behind it was going to be a popular subject in the next couple years. So we branded the whole network around forensics in primetime. We scheduled it so it was on every single night because we had enough of them; they were cheap to make. Ed Hirsch was the executive in charge of those productions and they were good stories, self-contained in half-hours, everything you would want in a franchise show and we really built everything around forensics in primetime. We created a forensics curriculum for high school students which was free off our website, and it really helped elevate the network to a different place and really began to shed the misperception that all we did in primetime was air reruns of trials because we didn’t. The amount of experimentation that the company was willing to undergo at that time was, again, really remarkable, very brave. We did nationwide tours of forensics labs, we invented this forensics curriculum, we were very aggressive about what we did and ultimately it helped bring us on advertisers at the same time. That tour was sponsored, the forensics curriculum was sponsored. So not only was it good for consumers – they loved it – but at the same time it enabled us to win over affiliates who were a little skeptical of whether or not we could change our brand from one of just court to one of forensics.

NELSON: Yeah, and there was some controversy over that at the time.

SHAPIRO: Yeah, not as much as I think they might experience in this next change, but it was actually probably one of the first steps towards where they’re ultimately winding up now, which is reality. Now they’re going away from crime at night.

NELSON: Was there a moment… you undertook this change… At night forensics was there, and you said that that’s kind of a gutsy thing for them to do, was there a point at which you started to sense, hey, this is really working? Was there an episode or some kind of feedback?

SHAPIRO: Well, I don’t want to make seem like I created this change. They had been airing forensics in primetime and what we all noticed was that any time we put a premiere episode of Forensics Files on we popped a number, even with no promotion off-air people found it.

NELSON: They see that word on the guide…

SHAPIRO: Yeah! And then when we got that piece of research that 75% or 80% of the cable universe understood what the word forensics was we all sat in a room – Henry and Darren Campo, who was the head of research at the time – we all went “Ah-ha!” It was a real… you don’t have that many ah-ha moments and it became obvious. So we just really charged right at it and then when we started to seasonalize it, meaning “Here’s a whole new season of Forensics Files,” or we created our version of Shark Week – some ideas are worth stealing – so we created Forensics Week and it did huge numbers for us. So it became evident, pardon the pun, that this was going to work and it continued to work. It was a lot of fun and I learned a lot. I actually had to teach myself what forensic science was and understand it most notably because you couldn’t sit in a room with a bunch of forensic scientists and not understand what they were doing because then you just weren’t legitimate. But to launch a forensics curriculum became something that I felt was important because science in this country is a disaster. Students in our country rank in the middle of the pack in industrialized nations in science and math, and mostly I feel that’s because education in this country is not necessarily all that fun. But forensics is actually a mixture of physics and chemistry and a whole bunch of other scientific methods that people find very interesting. And so when we would create a fake mystery and go into a school and solve that mystery with the kids, you would see kids who were not necessarily turned on by science all the time getting really into it.

NELSON: Is it that solving the problem, solving the mystery that holds you? But in the end isn’t that just another form of story-telling, to figure out what the story is? Here’s how the story ends.

SHAPIRO: Absolutely. That’s exactly right. That story-telling – we wrote stories into these units of curriculum. We worked with the National Science Teachers Association to make it legitimate learning, but at the same time we worked with our television people to make it entertaining. You know what? To be perfectly frank, you go back to that addiction of television. One of my favorite things growing up – I talk about cartoons – was Schoolhouse Rock, and Schoolhouse Rock was Lynn Ahrens and Stephen Flaherty and a bunch of other advertising people hired by ABC to sell education, to sell learning. Conjunction Junction What’s Your Function – there’s a not a person my age who cannot sing the preamble to the Constitution. “We the people in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice and promote domestic tranquility,” we all know that. Conjunction Junction What’s Your Function – that lesson, and I actually got to work with Lynn and Stephen on Ragtime many years later because they’re actually big Broadway Producers and creators now. They wrote Ragtime, they wrote Once on this Island, they wrote Seussicle – so they transitioned themselves from advertising to entertainment through the prism of Schoolhouse Rock – the forensics in the classroom curriculum was really again another stolen idea. I knew we could make education fun because I’d seen it happen. Instead of singing and dancing and cartoons, we used mystery, which way back to Dickens, The Mystery of Edwin Drood – people love mysteries. Sherlock Holmes… kids even love mysteries, and so this became something that was very engaging and very important for me, and it was also a part of something I learned from Henry and from George which is you can do good work and do good work.

NELSON: So for you, part of what you wanted to be doing was not just promoting TV shows but actually some kind of public good kind of activity?

SHAPIRO: Again, I go back to the beginning of it – I was very influenced on how influential television could be. I guess I could use it for evil but I decided that very early on in my career I wanted to leave an impact, do something important. Part of that is as the son of a Jewish mother I have to be important, but on the flip side…

NELSON: And do good.

SHAPIRO: I always wanted to have kids and now I do have kids – I never wanted to leave something that was as unimportant as money behind. It would be nice to leave my kids something but it would also be better for me and for my family to have something to point to to go we left the world a little bit better than when we found it. My grandfather died when I was running my own business and at his funeral… he ran a gas station. He dropped out of high school, it was the Depression, he was one of seven kids, and he, from 14 years old, worked at gas stations and as an auto mechanic and then he ran his own gas station. When he died I went to his funeral and I was actually giving the eulogy and it struck me that there were 300+ people at his funeral most of whom I had never met before.

NELSON: Who are these people?

SHAPIRO: They all came up to me and said, “Your grandfather did this for me. Your grandfather did this for me. Your grandfather did this for me.” So that ethic stuck with me for a very long time and the idea that you can be a mensch, and at the same time he made a nice living for himself. The mechanic or the gas station owner’s joke is whenever they die and you open up drawers you see wads of one dollar bills, and he did, he made a nice life for himself, he sent two kids to college, he was always incredibly supportive of my family, but at the same time he was a mensch! And so that was something that has always stuck with me and the forensics curriculum and everything we got to do – and Henry is a big believer in this as well, the things that he does wherever he goes he feels it’s important to do good word and give back, so that was something that they allowed me to do at Court TV and it also turned out to be profitable for the network at the same time so it was a double win. So it was a great place to work, I really enjoyed it. I learned a lot there, I learned about television immensely – distribution and ad sales and programming, and I really enjoyed all the people that I got to work with there. And at the same time it was a really nice introduction to corporate life for me because I always was afraid of corporate life and Court TV at the time was not very corporate. They were co-owned by Liberty and by Time Warner, but the governance was never day-to-day.

NELSON: Were they more hands off so this was a more entrepreneurial…?

SHAPIRO: We were really a stand-alone network, and one of the last stand-alone networks at the time. As long as we didn’t drive the thing into a wall they left us alone until the board meetings once a year, and that was a big to-do. I’m sure Henry and Art had a lot more pressure put on them than I saw but we were pretty autonomous, and by the way, very successful. When Henry got there it was 29 million homes and going south. When I left it was in 80 million homes and going north and it was a very profitable business. So I learned a lot about running business, about television distribution, about everything you could… it was a paid master’s degree in cable television from the masters of the game. Henry and Art and Dan and Bob Rose – these people grew up in the cable industry. So while I brought something from the outside that was not necessarily the same old thing, I was also able to learn all the best practices and all the history of the industry on a crash course. At the same time, my first week there was the week before 9/11. One week to the day after I got there, 9/11 happened. You really got a picture of the people that you were working with.

NELSON: Under those circumstances.

SHAPIRO: Yeah, you really did. Again, it was a really great introduction to corporate life for me because had I jumped into a Viacom or an NBC or something that large right away, I don’t know that it would have been as easy for me to transition out of kind of indie culture, theater world into television, but this was a great path to travel because I got introduced to all the great stuff but without all the meshigas of a major corporation sometimes.

NELSON: What was it like there on 9/11, 9/12? Obviously it struck you.

SHAPIRO: We pulled together, I mean New York did, and that’s also probably the day I became a New Yorker. I still root for the Philadelphia sports teams, and I still consider myself from Philadelphia or south Jersey, but that was the day I became a New Yorker. There’s no question about it. We all walked home. It was a tough time but you learned the mettle of a man. You learned what these people were made of. I don’t think I could have been as galvanized into the organization as quickly as I had been had that not happened. You always look for the silver lining in something and this is that to me. It was the day that I understood what it meant to be a New Yorker, it was the day I understood how to be a member of a larger community than I’d ever been a part of up until that point.

NELSON: And you think that’s what they learned about you? You talk about what you learned about them, what did they learn about you?

SHAPIRO: I couldn’t tell you what they learned about me. Over the course of a couple years there I think what they learned about me was just because something’s always been done some way isn’t necessarily the right answer.

NELSON: And are you somebody that doesn’t easily take, “Well, this is the way we’ve been doing it so we keep doing it.” That’s just not you.

SHAPIRO: It’s not an acceptable answer. Is there a good reason? “We do it this way and it’s been very profitable, here’s the success.” Well, that’s one thing. But “We’ve always done it that way,” or “It’s not done that way,” usually means I haven’t asked.

NELSON: And not only do you not accept that but does that almost drive you to say, “Wait a minute, I’ve got to look more closely at this because when I hear that this is waving a red flag.”

SHAPIRO: It’s usually typically a red flag for me. It can be a symptom of stasis which what I’ve learned in my relatively short period of time in the cable industry – I mean, I’ve been in the cable industry, I got that job in 2001. That was my first job in television. I had worked for television companies up until that point but the first job that I had in television was in 2001. It’s 2007. That’s six years! So what I’ve learned in the six years that I’ve been in the television business is that stasis will kill you. We cannot afford as an industry – look at the record industry! If you resist change, just for resisting change’s sake, you will die. You will be overcome by the open source mentality that is growing in the media industry. I know we’re way off path here, but I’m very fond of asking, when I’m in an environment where I’m in front of a room full of people on a panel or something like that, I typically ask how many people here have used Linux – and Linux is an operating system that is user generated, that is open sourced. It’s created by everybody and improved, it’s like a Wiki. And nobody raises their hand because nobody uses Linux, not that many people use Linux.

NELSON: And of course they’re coming out of a corporate climate and somebody in IT says, “Okay, here’s what we’re using.”

SHAPIRO: Yeah, and typically everybody uses Windows or Mac, sometimes you see Mac.

NELSON: That’s when they’re being really radical, they use a Mac.

SHAPIRO: Right, Mac, right – ooh, the creative types. But when you ask how many people here use Google, well, everybody in the room raises their hand because everybody uses Google. In fact, for many people it’s their homepage. Then you’ve used Linux. Every Google server is a Linux server. So when you resist change for change’s sake, you miss opportunities that other people can then take a hold of. I’m not a change for change’s sake person either. Just because it’s working doesn’t mean it needs to change either. But I have found that when I ask enough questions the right answer emerges, and sometimes it’s what’s already being done and sometimes it’s stuff that’s completely different, and more often it’s a combination of what’s working and what’s new.

NELSON: But you changed because you were at Court and then you left. How did that come about? Had you just done what you felt you could do?

SHAPIRO: I had a great corporate coach at the time who’s name is Gloria Hahn that Court TV provided to me, and what she said to me was “You have a lot to offer but sometimes you get in your own way. Oftentimes you want things to change in your path when they’re not going to change.” The structure of Court TV was the structure of Court TV and it became clear that other opportunities needed to be explored in order for me to get where I needed to be in my career. I didn’t want to be in marketing my entire career. There was a point in time when I moved from the Public Theater into my own business that I realized I couldn’t go away in the summer and direct plays. I just couldn’t. I had a business to run. My clients couldn’t hear, “Oh, he’s in the middle of Pennsylvania directing The Foreigner.”

NELSON: Call him back in September.

SHAPIRO: Yeah, right, exactly. And by the way, cell phones weren’t that prevalent then so it was harder to stay in touch. So I had always promised myself, at that point I said to myself, “OK, fine, I’m giving up directing, I’m not going to write this stuff. I’m going to concentrate on business and marketing and things that have made my career up until this point, but someday I’m going to get back to creating art.” And that’s what I wanted and I wasn’t going to get that at Court TV. It just wasn’t my job, it wasn’t in my job description. There were plenty of talented people who were already doing that. So I met Ed Carroll at an interesting time in the life of Cablevision and Rainbow.

NELSON: And Ed’s position at the time was?

SHAPIRO: Ed was at the time the general manager of AMC and IFC, but it was clear that the AMC job was a pretty big one and there needed to be a dedicated GM to IFC, and they were losing their head of marketing at the time who was a very influential person at the network. She was really basically running the network up until that point.

NELSON: And that was?

SHAPIRO: Carolyn Bach. Because he was concentrating on AMC there had been a lot of turnover at the company at the time. So he wanted somebody who could come in and be that senior executive, not necessarily take the GM’s job but maybe grow into the GM’s job and that’s the job that they offered me.

NELSON: With that opportunity to grow into it? Or was that something that was maybe a little more vague?

SHAPIRO: No, he and Cathy Doerr basically said in a couple of years if you don’t suck you will have the opportunity to try out for this job. It was not a promise, it was not a guarantee, but it was head of marketing for IFC, which is a cool job in and of itself, and then on top of that I had the opportunity to learn more parts of the business at the same time and grow into a bigger role if the opportunity arose. It was also a really different place for me to be, from a non-fiction, general entertainment network…

NELSON: Reality, courts…

SHAPIRO: To independent film and a whole new world, and my first gig was Sundance, and then I got to go to Cannes. It was a very interesting job, obviously, and a brand that I thought was all opportunity. People new the Independent Film Channel but not that many people watched, not that many people knew exactly what they were doing, but it was very widely distributed for a digital cable network.

NELSON: Do you recall at the time what that was?

SHAPIRO: It was in the 30s, 30 million.

NELSON: Well, that’s pretty good when you look at what it was.

SHAPIRO: For digital cable penetration at that time? There were very few holes for the digital penetration distribution. And it was a very profitable network. Because it was solely on the digital tier and was commercial free they were able to garner better subscriber fees. So it was doing quite well.

NELSON: And was it largely just showing independent film at that point?

SHAPIRO: Other than Dinner for Five, yes, they were primarily showing independent film. They had a couple documentaries that they were doing.

NELSON: So they didn’t have a lot of original production costs?

SHAPIRO: Not that much, but some.

NELSON: I was just looking at this economic structure.

SHAPIRO: The overwhelming majority of the programming costs were buying films, and by the way, it’s still that way. It’s still the vast majority of what we spend because it’s still maybe a little less than 90% of our programming model is still independent uncut films. So I was brought in and really it was a hard time at Rainbow at the time. They had just sold Bravo so a lot of people had lost a lot of co-workers and there was almost like a Solomonesque decision to be made. Who stays at Rainbow? Who stays at NBC? It was like dating somebody after a divorce.

NELSON: And I imagine at the time, at least my perception from the outside, AMC, Bravo, IFC – it was kind of like a package.

SHAPIRO: Oh, and they all worked on each other’s stuff, too. So it was really tumultuous.

NELSON: So you’re pulling this piece out.

SHAPIRO: Now granted, Cablevision got 2 billion as far as assets so it was a really nice… Well, beyond that, it was “Look, you people. You built this thing and it’s worth 2 billion dollars. Nice work!”

NELSON: But did they benefit from that?

SHAPIRO: I’m not at liberty to say. Some did, I imagine, and some didn’t. But the hard part was that it had created a little bit of a morale problem. It had created a brand problem because so much of the identity of IFC – all of our share drives were still called Bravo, all of the carts in the hallways still said Bravo on the side, so there’s an identity crisis to a certain extent and a little bit of a morale problem as well. So I was able to come in, I was given a great wide berth, a learned a lot from my coach that I had had at Court TV who said to me “Sometimes your intelligence is seen as knowing it all. Sometimes your sense of urgency is seen as impatience,” and I read a great book called The First 90 Days which told me, the first sentence is “50% of all senior executives who make a transition fail.”

NELSON: That was the beginning of the book?

SHAPIRO: That’s the first sentence in the book, and the major reason for that failure is misdiagnosis. They come into a new situation and they think they know everything. “This is all shit, I’m going to do this a whole new way, let me teach you how to do it,” but in reality they miss the things that are working, they oversee people who are doing great, they mistake title for success sometimes, and they bowl over the community and therefore gain no trust, and can’t really get anything done. And so the goal of the book is to make the senior executive profitable to the company in the first 90 days and therefore change the DNA of that person inside that organization. It was a really influential book; I had a great coach who had teed me up to listen more, to not force my opinion into situations, to not misdiagnose, to be more patient, and the person I was at Court TV – and anyone you ask at Court TV will tell you this – was great, full of energy and so on and so forth, but jeez, he was a little impatient, nothing happened fast enough. The person I was there… if I had come to IFC and said, “I need to be GM today! It’s not happening fast enough,” and that was my instinct, I have to say to you.

NELSON: What impelled that?

SHAPIRO: You know, we could lie down and I could tell you about my psychology…

NELSON: This is a sit-up interview.

SHAPIRO: It was a fear of wanting to prove yourself and being on some clock inside my head, and you see a lot of kids who come out of school now, especially now, who have this impatience and this entitlement without having necessarily proven themselves. While I got this job, I must have deserved it to a certain extent, none of these people knew who I was. I had no reason to expect their trust from day one, so I had to build that. So I asked a lot of people a lot of questions. I basically served as a consultant in my own head for the first 30 days trying to find out what exactly was necessary, what was needed, where the silos were, how to tear them down, and it was a really eye-opening experience for me. I don’t know about the people who were there, but I learned a lot, I learned a lot about people, I learned a lot about how to relate to people and how to get things done, and oftentimes I heard from people who were now my peers or my employees, “Well, that’s not the way Cablevision works. That’s not the way this place works. That’s not how it’s done here.” And then when I talked to the people at Cablevision or Rainbow, they go, “Well, I guess we’d be open to that but we’ve never been asked.”

NELSON: So that was that old red flag, “It’s not done that way.”

SHAPIRO: Let’s get in a room and see what we can do. We changed the brand pretty much overnight. We always assumed that independent film was for women 25-54 – this was the thing that I learned fastest. Why did we assume that? “Well, that’s just the way it is.” Based one what? And then we bought some research and we saw that, no, our audience was really men 18-45. So we just overnight changed the brand to Uncut because that’s what these guys want. Also 40% of our audience knew we didn’t show commercials but 60% of our audience had no idea that we didn’t show commercials. No clue that we didn’t show commercials.

NELSON: This is your audience?

SHAPIRO: Yeah!

NELSON: Are they watching?

SHAPIRO: Well, it’s digital cable. Just because you and I might watch a movie start to finish, that’s not how the world watches IFC, or it wasn’t then and it’s still not. We’re a digital cable network. People surf. They come in for 15 minutes, they watch the end of the movie, they don’t remember that we don’t show commercials. Certainly when they’re surfing they don’t go, “Oh, IFC. That’s that channel that doesn’t show commercials.” But when you ask them if you knew we were uncut and uncensored, would you watch more of the network, 80% of them said yes. It became a very obvious answer to a very serious problem and we went that way. At the same time…

NELSON: With one word, by putting one word on there.

SHAPIRO: Uncut, TV Uncut, and it became exactly who we were, and the cool thing was it was a brand that we already were. We didn’t have to change the network in order to earn the brand, it was the brand. At the same time we used this Uncut model and this cool indie model to bring on advertisers in a non-commercial atmosphere – Target, Volkswagen – but we did it in a way, we said there’s no clutter. There’s no commercials. Let us make a short film for you. We’ve increased sponsorship from that first year we did it by about 700% since then – no commercials, no ratings.

NELSON: And what do they get? They’re not getting a 30-second spot, right?

SHAPIRO: No ratings. We won’t show their commercial. We won’t show their commercial. We don’t air Target’s commercial, we refuse to air it, and that frankly pissed them off the first time we said that to them.

NELSON: “Who the hell are you?!”

SHAPIRO: Yeah, but we proved to them that a brand rub-off is better for your in this environment. You want to be connected to the films. You want to be connected to the brand that is IFC. So we made short films starring indie actors for some people, for other people we made interstitials about the films that people were about to see and then we get the hell out of the way, and all the time we basically say these brands help IFC bring this film to you uncut. And the audience goes, hey, that’s interesting. Now there’s an example of us having a huge advantage in the marketplace which we thought was a disadvantage. We have research that shows that brands that advertise on IFC have a better impression in the marketplace than brands that don’t, their competitors that don’t, because of the connection to indie film and the fact that they’re willing to be brave and bring this to you uncut and uncensored. The intent to buy goes up, the warmness towards the brand goes up, and it’s, I think, the future of television marketing. I don’t think we’ll be looking at massive 30-second commercial pods in ten years. Why would we?

NELSON: Because we always did it that way.

SHAPIRO: But the audience has a fast forward button now and they’re skipping the ads, I don’t care what anybody says. Especially the more intelligent, upscale and discriminating they are, the more likely they are to have that technology, know how to use it and be less interested in things that are not relevant to the experience that they’re having. But Target says “You’re watching the Independent Film Channel brought to you by Target and now here’s an awesome film uncut and uncensored that we think you’re going to love. Enjoy.” The audience goes, well, that’s pretty cool.

NELSON: “Thank you very much!”

SHAPIRO: Yeah. So that also got us into really looking at what else we could do with the brand and that’s where the original programming really started to take off.

NELSON: And talk about that.

SHAPIRO: Let me go back for one second. So I was there for… I thought it was going to be a couple years before I got to run the channel and the success of the network ramped up a little bit in my first year there but it was not a rocket shot to the moon. The thing that happened was I was able to galvanize the team. I was able to build a team out of what had not necessarily been one before. Cathy Doerr leaves, Ed Carroll gets promoted into her job. He’s now running all three networks – WE, AMC, IFC – and the job of general manager of IFC is really now open. I got the gig. This is ten months after I’ve been there. Again, no reason to think I’m going to be a great general manager, but what Ed, I think, if you talk to him and what other people have said to me, is when they looked around and they saw that there was a cohesive team that people believed in, it was not a hard decision to make, and Cathy actually on her way out the door made sure that the gig was going to be mine ten months after I got there. Very lucky. Very, very lucky. Right place, right time.

NELSON: Well, for an impatient guy that’s a good time table, right?

SHAPIRO: Yeah, but in being patient I got the timetable that I wanted, you know what I mean? So in concentrating on the work and in concentrating on proving myself everyday, and that’s what I worked on everyday I was there was be patient, listen, be empathetic, take people’s opinions, formulate strategies that have a complete buy-in before you say this is what we need to do, or in fact don’t present it that way. What do we want to do? That enabled me to be so distracted that I didn’t care what the timetable was and by the time I got the gig it was too fast. It was surprising how fast it had happened. But it was the right time… I’ve been very fortunate. The Public Theater job was one I didn’t deserve. The GM’s job at IFC was something that was way earlier than anybody in the industry thought I’d ever get a gig like that, including me. So I was at the right place at the right time. I was very lucky, but as my mom would say, knowing what to do with opportunity is also part of the game. And so what was great is that because I had listened and done as much research as I had up until that point, I had a better idea of what was needed from that point on. Reorganizing the programming department immediately…

NELSON: So let’s talk about it because you’re saying now you knew what you had to do, reorganize the programming department… what did you do?

SHAPIRO: We organized it into scripted and non-scripted so that Dinner for Five and the non-scripted stuff fell in one bucket and documentaries that we had done, like Decade Under the Influence which was done before I got there and Z Channel which had been in production before I got there but I inherited fell into another bucket, and it gave those people ownership as opposed to kind of stepping on each other’s toes which was always a problem up until that point. In the non-fiction world we pursued things that fit that uncut agenda, the idea that we would basically to a certain extent, and pardon my French, say “Fuck you. We’re a movie network? Let’s do a documentary that rips open the movie business, This Film Is Not Yet Rated,” which was the first project I green lit when I was there. Dinner for Five, which was a very popular show by our standards up until that point, especially with cable affiliates, was really expensive and really it had plateaued, and so I said this is something we can no longer afford to do. I know it’s dangerous but we can take that money and reinvest it in scripted programming which is something we need to begin to do if this is going to be successful because that’s what our audience wants based on the research. So we pursued documentaries in a big, big way. The first thing I green lit and the first thing I really wrapped my head around was This Film Is Not Yet Rated, which was a documentary about the MPAA.

NELSON: Right, right, and did that create controversy out there, and to the extent it did were you comfortable with that?

SHAPIRO: I’ll be hones with you, many of the things that I’ve tried to do in my career I was told not to do at first. That one not so much because it was dangerous to the motion picture industry – I was worried that we would lose money from the motion picture industry because they do sponsor the network in a big way, but on the flip side it was more about whether this would be an interesting documentary to anyone.

NELSON: About a rating system.

SHAPIRO: It’s about bureaucrats.

NELSON: It sounds a little dry.

SHAPIRO: But what we found out was that it was something that people were interested in, that nobody knew how films were rated, and that the ratings system that the MPAA had enacted was really a censorship device and it was wholly owned by the five or six major conglomerates that all owned the major studios who all paid the salaries and the budget of the MPAA. They owned it. And films that were made outside of that system, independent films, got harsher ratings than those that were made inside the system. The director, Kirby Dick, who was an Academy Award nominee at the time, and still is a former nominee, camped out in front of the ratings board for a year. Nobody knows who these people are. Their identities were held secret, which in and of itself, why? There’s no reasoning for that. The system was really untransparent. He followed these people to and from work, he outed them, found out who they were, put that in the film and then submitted the film to the MPAA for a rating and kept filming. What an interesting, eye-opening experience! It was fun. I got to name that film, that name was something that I came up with which is a good example of the marketing thing and the art thing kind of marrying.

NELSON: Yeah, it’s a great name.

SHAPIRO: And I got to contribute to the… this is Kirby Dick, this is a really renowned film director, but he was very collaborative because everything I brought to the table was never about the corporatization of the film, it was just making the film more entertaining and better for our audience and understanding who our audience was. Who’s it for and why do they want to watch it? We brought in an animator that made it a lot of fun, we pushed up the investigation part of it because we hired a private detective for part of it, so we green lit it at Sundance one year and the following year it gets into Sundance, and then two years after that at Sundance the MPAA announces that they’re going to change their rating system in part because of what the film had done. So during that time as well the film became basically a huge brand carrier for the network. It was a big fuck you to the film industry at a time when film was in our name.

NELSON: But also uncut was in your name, right? So you’re really playing with that.

SHAPIRO: Right, and when we unveiled it at Sundance that second year, there’s a moment at the end of the film – the appeals board is completely secret, nobody knows who the identity is, and unlike that raters who are just basically average people who are hired and have a job, the appeals board are people in the industry, major players in the industry and their identities are kept incredibly secret, and including some clergy actually, which is really disturbing. So we outed those people in the last couple of seconds of the film at Sundance. This is the first time anyone’s ever seen it, in the largest theater at Sundance, and they’re all in the room. So there’s this gasp!

NELSON: They wanted to see what this was all about.

SHAPIRO: Yeah, but I don’t think they knew that they were being… and I didn’t realize when we made the film that they’d all be sitting eating Jujubes right there. So it was a really bizarre experience. But I got calls from people in the industry going that was what was necessary, it is a weird system, it needs to be tweaked, it needs to be changed. And Jack Valenti then left and they have a new head who is a much more, I think, reasonable person, and they’re making revisions to the system based on input of independent filmmakers and other people like that, and it was a really gratifying experience. It is, I think, the epitome of programming as brand. It’s selling tremendously on home video, it’s doing really great on Netflix, when we aired it it became the highest rated documentary that had ever aired on the network, and so by being that courageous and that different the network and Cablevision, who allowed me to do this, they didn’t have to allow me to do this – it was also Fair Use, which is a whole other controversial subject unto itself – we did so many good things for the brand not just because it’s important and it was good work and we changed the system, but it also happened to be profitable and highly watched and good marketing. So you can have those things overlap and it just reinforced everything I’d learned at the Public and in my business, and now here I was making art again and using the things I had learned as a marketer, and it was probably one of the most important projects I’ve ever worked on, and certainly most important to my career and one of the most gratifying things I’ve ever done.

NELSON: And I imagine that was so important to IFC in terms of changing how people perceived what you were and what you were doing because it was an original work.

SHAPIRO: They knew it was for original programming.

NELSON: Yeah, so you really established that.

SHAPIRO: Absolutely. Parallel to that, we were making scripted programming. We launched two shows – the Minor Accomplishments of Jackie Woodman, and another one called The Business. The Business was actually an idea that I had had with a director that I met at a film festival and we were really drunk one night and it turned into a series. What we were able to do was create, I think, really fresh, original comedies at a fraction of the price of most of the people who produce television. The Business is around $200,000 an episode. Minor Accomplishments… is a little bit more than that, a little over $300,000 an episode. For a half hour of television, that’s very economical and I think the shows hold up. I think that they’re really well written and really well performed. They don’t have movie stars in them and they don’t look like feature films, but the audience cares less about those things when the stories are good, when there’s people in them that they can relate to. We really have found, I think, our voice in the last couple of years both online and on the network. Now we’re going to launch an on-demand channel in January. Our audience knows that when they come to us they may not always like what they see but they’re never going to be bored and they’re never going to get processed cheese. And that’s something that has created a brand that is larger than any one piece of programming in and of itself, and that’s important and that’s what makes, I think, an Apple, that’s what makes a Google, when you can transcend one specific thing and really become a culture that people want to be a part of. That’s what will win. IFC doesn’t have enough money to compete on a business model to business model basis. IFC does not have enough money or resources to compete on a marketing spend to marketing spend basis. We spend per year what HBO spent on Thursday in marketing.

NELSON: And today is Thursday so…

SHAPIRO: Yes. I mean, they spend more today on Ricky Gervais’s show than we will spend the entire year. In the new paradigm when open source becomes the model and fragmentation of audience becomes a regular thing and disintermediation of what’s on at 9:00 is the norm, culture versus culture, the way you come about who you are and what you believe in is going to be way more important than the billboards that you take. I learned that at the Public Theater, I’m learning it again at IFC and it’s working. This summer we did a documentary series called – one of the things that came out of This Film is Not Yet Rated is that sex is rated more harshly than violence is. Sex, bad; violence, good. When you think of the movie industry as a major marketing tool that for 50 or 60 years has said sex, bad; violence, good, it’s not surprising that we have a belligerent society that feels it needs to go to war every fifteen minutes. It’s what we’re sold. So there’s a challenge to that system that I wanted to take on so we made a documentary called Indie Sex: Four Nights of Great Sex, a documentary series by two talented female directors, which there are not enough of in our industry, that really took an intelligent, thoughtful no-holds barred look at sex in film and why certain things were allowed and certain things were not. We did it over four nights and that became the most watched thing in the history of the network – more than Bend It Like Beckham, more than any feature film we’ve ever bought, more people watched that than any thing else.

NELSON: But how do you do that on basic because you’re walking a line there. This isn’t HBO where you can always say, hey, they’re paying ten bucks a month for it so they can get whatever they want.

SHAPIRO: There were a lot of arguments about that very thing and it was no-holds barred. We showed things on television that no one’s ever showed on television before and there is a mentality afoot in the industry not to be first to do things like that. Some of those people actually happen to work at my company. And there are lawyers who were worried about decency laws, local decency laws, and then there’re new national statues for child pornography that you need to make sure that you don’t cross over, but this wasn’t simply salacious, this was a really intelligent look at it so I felt we had permission. We aired it at midnight and we put it through the prism of a documentary film, and not one phone call, not one single phone call to complain. We’ve aired it several times since then and it is a viewership machine and we’re releasing it on home video. Sex sells, go figure.

NELSON: Who ever heard of that?

SHAPIRO: Again, it’s not like I came up with that idea. HBO’s been doing it for a number of years. Sheila Nevins is probably in addition to one of the most important people in the history of documentary film, she’s also pretty good at selling things that turn people one – Taxicab Confessions and things like that. So we knew there was an audience for it and we knew our audience was thirsty for it, but we also knew we could make a good piece of art out of it as well, and we did. It got very well reviewed and again, because I think we handled it well there were no issues for it. But I also learned a lot about the law and about how to handle affiliates and how to talk to affiliates and get their buy-in. I called affiliates and said this is what we’re doing, what do you think?

NELSON: Beforehand? Did you call them beforehand and say we’re going to be doing this and we aware of it so people aren’t blindsided?

SHAPIRO: Some, some, not all. And what do you think? And more often than not they said this is a good film. That got their buy-in in a way that I thought was important, I think. I think we would have gotten in trouble if they had found out about it after the fact, but it was also, I think, a good management lesson for me as well. People want to be heard. They don’t want to be surprised. So now we’re working really aggressively on original scripted programming in a big, big way. We have a new sketch comedy series called The Whitest Kids You Know, which is the only uncut sketch on TV, and these guys are brilliant. They came from the college humor kind of landscape, but the level of intelligence that they bring to the format is not something I’ve seen since probably Monty Python – really intelligent and flat-out funny stuff, but bold and different and original. You know, a sketch that goes on for 12 minutes. Everybody in the sketch comedy world will tell you, you can’t do a sketch that’s 23 minutes long, no way!

NELSON: You can’t maintain that!

SHAPIRO: And yet…

NELSON: They do.

SHAPIRO: You look at The Simpsons which is basically a half an hour sketch every week and there is a level of things get funny once again if you just stick with that joke long enough. Monty Python – spam, spam, spam, spam, spam. Why is that funny? Because they won’t stop saying spam. So we’re really experimenting with the format there. We’re distributing the first season online now and then we’re actually going to premiere the first season on-demand in high-def before it hits the network. The cable operator loves that. The ratings people say, oh, that’s going to destroy your viewership. I disagree. I think you look at The Office and what happened with I-Tunes and them, they were basically being cancelled until it became an I-Tunes hit. This year, Gossip Girl, same thing. That show was doing eh, but then when they factored in plus seven on TiVo and DVRs and I-Tunes, it’s got a big audience, a pretty big audience of 12-17 year old girls predominantly, which is a very profitable audience as well. We are going to operate in a multi-platform way starting today. Because it’s on at 9:00 is a stupid way to think about your business and we’re moving from a linear only network to a multi-platform on-demand programming channel that is wherever you want it whenever you want it without disintermediating the business of the cable operator, working with them to make sure it’s good for them. Therefore premiering in high-def, on-demand before it’s on the network, and we’re going to do that with every piece of original programming that we’re doing in 2008, including a documentary that we’re doing on the death penalty and an anime series and a new series about a rock band, they’re all going to be premieres in high-def, on-demand first because I believe that the internet for watching video is nice, but the biggest electronic being sold this Christmas season is not computers, it’s high-def television sets.

NELSON: Yeah, and it has been for a couple of years now.

SHAPIRO: People don’t spend that kind of money on a big ass television set to watch things on a computer, so I think that the hysteria and the pandemonium and the just wonderful buzz that’s around video on the internet is a precursor to what is truly at the heart of that experience – on-demand. On-demand is what people want. It’s not because it’s on the internet. It’s convenient and it’s on the internet. When it’s convenient and it’s on my television set, well, that’s what I’m going to watch. Now if I go out of my home I’m going to put it on my I-Pod or I’m going to put it on my laptop, but if I’m at home I’m watching it on the thing that I hung on my wall. I’m not going to watch it on the thing that sits on my desk. So we feel that our programming advantage can be made on-demand in the coming years. We also feel that we can adopt… the ad sales strategy that we have on-air is perfect for on-demand. If a brand brings you an uncut, high-def program and introduces it with a little brand film and then gets the hell out of the way, you’re going to feel good about that brand. We are beginning to adopt that to our on-demand strategy and we’ll see how it works. I think we’ll land probably the first major on-demand sponsorship in the industry in 2008, one that kind of transcends what other people have done. My goal is to really reinvent the television model – linear network, website, on-demand channel all simultaneously co-existing without necessarily always overlapping. There will be things that will only be on TV, there will be things that will only be on the website, and there will be things that are only on-demand. Dickens. Every Tuesday they refresh the on-demand library. If you can teach people that they will go to it. It’s Tuesday, let’s see what’s on-demand. I’m looking to create the first on-demand hit. That is my goal for 2008-2009, and I think we’ve got the programming to do it. I think we’ll be the first to that space. If not, we’re going to kill ourselves trying to get there. People will tell you, that’s not the way it’s done. You premiere it on the network first and then you put it on-demand. But that’s the way we’re going to go.

NELSON: Now you talked about the internet as not a place for looking at long-form programming, but it is part of your whole mix. So what do you do with that? How do you use that?

SHAPIRO: It’s not necessarily not a place to watch long-form programming, it’s just it’s chosen out of convenience, it’s not chosen out of desire, meaning if I’m the college kid and I don’t get cable, well, then I’m going to watch something on my laptop. If I’m in an airport…

NELSON: But this isn’t maybe the most desirable place to watch that, but how do you use the internet as part of this whole mix?

SHAPIRO: We’re programming it as its own channel. So Trapped in the Closet which was this series of ten episodes of original programming premiered on the internet, was exclusive to the internet, was exclusive on our site, and it was a phenomenon – 1.5 million unique hits.

NELSON: What was the running time?

SHAPIRO: Each episode was between three and seven minutes in length.

NELSON: Ah, okay, now we’re talking about a very different animal than a 90 minute movie.

SHAPIRO: Sure, absolutely! And I don’t think the vast majority of people in this world have the patience to sit and watch a 90 minute movie (on the computer). That said, I watch DVDs on my computer on the plane all the time.

NELSON: Well, you’re trapped – speaking of trapped in the closet!

SHAPIRO: When the quality of the video gets better, people will watch long-form online when it’s convenient, but given the choice between that screen, the little one on my desk, and the big one, I’m going to choose the big one because it’s there. So it’s a convenience matter. Where am I?

NELSON: But how do you use that as far as extending your brand, serving your audience and other things you are doing?

SHAPIRO: Our audience likes to watch video online, they like to read online and they tend to do it on the 12s – lunchtime and midnight. So we provide a lot of programming online – live coverage of the Cannes Film Festival… We used to shoot the closing ceremonies of the Cannes Film Festival live, very costly and on at 2:00 in the afternoon – not a great idea – on a Saturday! So it was okay. Now we do live coverage 24/7 from the Cannes Film Festival on our website and we see huge peaks at lunchtime and huge peaks at midnight. That’s only available on our website because that’s what it’s there for, that’s what a website’s there for. And that’s long-form content. That’s streamed constantly. There’s no end to it for two weeks and then we archive it and people watch it. But we’re creating shows specific to the website. We have a user-generated film site that people can upload their films and vote on their favorites – that is exclusive to the website. The best rated films get to the network but predominantly it’s a web-only product.

NELSON: And talk about the user-generated. Where those come from, how they wind up on your site – are people just sticking them up there or is there an editorial decision making process?

SHAPIRO: It’s a short film site. It’s not user-generated – you won’t see cats jumping on trampolines, you won’t see Mentos being trapped in Cherry Coke – they are real short films. Some of them suck and some of them are great. Word has just spread. There are about 4,000-5,000 film directors who give us films. They upload it, they give us the right to use it, and they keep the right to use it themselves. They’re not giving it away to us but we can now use it on any platform that we want and it’s become a Pro-Am model of program development for us. It’s very popular with our users, it’s very popular with our web browsers and it’s very popular with our audience, but predominantly what we found with it is it’s a great way to develop new content. We found talented people that we now hire to make stuff for sponsors. We found new pitches there that we never would have found any other way, and the concept that no one is smarter than everyone, that you can’t just have this top den management model and have that exist in the current environment – that has really come to us through this prism. It’s a great site and I think it has everything that’s great about user-generated content there, but I don’t imagine that user-generated is necessarily the future of all content. I think this Pro-Am model, taking raw talent and matching with people who know the business and filling needs in the business – I have brands that want to make brand films but they don’t want to spend 20 million dollars doing it. I can match them up with a director who still understands how to make something for 800-900 hundred dollars and meet somewhere in the middle, and again, I think we’re teaching the artists business and we’re teaching the businesspeople art, and we’re really figuring out a way that, I think, is going to be a model to follow. You watch what Current’s doing – they have a very good model that way, too, on their website and on their network – and that Pro-Am model, I think, is really what the result of all this user-generated hysteria will be at some point.

NELSON: And obviously some of these Ams become Pros…

SHAPIRO: That’s what they want, right.

NELSON: …because there’s talent and that’s the way to get exposed, whereas You Tube, a lot of it is just people fooling around.