Interview Date: February 16, 2022

Interview Location: Buford, Georgia, & Denver, Colorado, via Riverside.fm

Interviewer: Stewart Schley

Collection: Hauser Oral History Project

STEWART SCHLEY: Greetings. Welcome to this edition of the Cable Center’s Hauser Oral History series. I’m Stewart Schley in Denver, Colorado. Via the magic of the internets I’m connected today to Wallace, but we’ll call him Wally for this interview. Wally Snedeker who is — his career has been so intertwined with the modern era of cable television that he used to be called Mr. Cable. So Wally, we’re thrilled to have you with us today.

WALLY SNEDEKER: I’m happy to be here.

SCHLEY: I want to ask, you were born in 1928, so how young are you as of today?

SNEDEKER: I’m 94.

SCHLEY: Ninety-four years young.

SNEDEKER: Yes.

SCHLEY: Ninety-four years young and you’ve spent a lot of time in the general management positions throughout the cable industry, but before all of that I would like to invite you to talk a little bit about life as a kiddo. You were born and raised in central Ohio and the bio that has been provided to us by your wife Wanda tells me you were a tinkerer, you were the kid who liked to take apart electronic stuff. What was that all about?

SNEDEKER: I don’t know. I just wanted to do it. My mom used to get so mad at me, “Are you going to put that back together the way you found it?” But I was born in 1928, January 26th, and my mother and my grandmother raised me. I didn’t have a father to guide me in anything. And later on in life my mother’s boyfriend was sort of a father figure to me and he taught me the value of hard work and gave me a job where he worked when I was 14 in a calendar plant. So I was doing okay until I started a fire. I was working too fast drilling holes in calendar pads (laughter).

SCHLEY: Okay, well, everybody has their moments in early career. But that trait or that fondness for electronics would serve you well as you began your career. You enlisted in the Navy in the World War II era and just talk a little bit about that period of your life.

SNEDEKER: I believe I’ve got a guiding angel that guides me along because I actually enlisted in 1945 while the war was still on, along with 12 other of my classmates and they said, “We’re not going to take you until you graduate from high school.” So okay. So I did my senior year and what guided me into electronics was my chemistry teacher, Mr. McKissick. He was also my physics teacher. And I almost flunked physics. When I got to chemistry in my senior year my brain must have kicked in. I was an A student in chemistry. He would never give me an A. He says, “Wally, I know you’re cheating. I can’t figure out what it is so I’m not going to give you an A. I’ll give you a B.” Well, the other guiding light was one of these former students came into the class, he was a Navy guy and he was in his uniform and he was third class petty officer and he wanted to tell us all about going to the electronics school, and I think he went in Chicago on Navy Pier. And he just — it was so interesting, I talked to him and Mr. McKissick overheard me talking to him and he come out and said, “Don’t waste your time, Wally, you’ll never pass that Eddy Test.” And so that encouraged me (laughter) so when we finally went into the Navy, we went to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. It was outside of Waukegan, Illinois, and there were 10 of us from the high school that were in that company. I still remember the name of the company, it was Company 207, Green Bay. And we got a number that we had and said, “You’ll never forget that number.” I still remember it, 5710904. And anyway, they give you an aptitude test to see what kind of brain you got, I guess, and where they thought you would best be suited. And evidently I got a pretty good score because I had several schools I could have gone to. And lo and behold the Eddy Test came up that I should take the Eddy Test and that’s the one I took. And my guardian angel helped me pass that test and so I went to Treasure Island for 13 months to the electronics school. And that was some tough school, I tell you. That was — they taught you everything from mathematics up until radar and identification, friend or foe, equipment. You got to do everything and you got to learn how to take it apart and put it back together and how to troubleshoot. And it was very — I loved it.

SCHLEY: And you can, I think, draw a link from that experience to what you went on to do in the cable industry where electronics knowledge and willingness to sort of experiment were important. But how does a kid get — how do you get into this business called community antenna television or cable television from where you were? How did that happen?

SNEDEKER: Well, when I got out of the Navy I went to work for the Ohio Power Company and it was sort of electronics. It was we had a mobile meter lab that we tested all the single-phase kilowatt hour meters around the state and one of the guys I worked with was Robert Morrison. So he knew of my Navy experience and being in electronics, which would later come to help. He left just before I did. He went to work for Claude Stevanus in Coshocton as an installer and I went to Columbus North American Aviation as an electronics electrician. They promoted me to take care of all their two-way radio equipment and I had my own little place out on the flight line where I had equipment and everything. It was fun. But while there they paid for schooling if you wanted to go to any schooling. And there was a school in Columbus called RETS, Radio, Electronics, and Television School. I knew television was coming and I thought boy, I don’t know much about television so I’m going to go to this school. So it was a night school and that got me trained for television and of course Bob Morrison knew about that too because we visited back and forth because we were good friends. One day he called and said, “Are you coming to Coshocton for Thanksgiving?” And I said, “Yeah, we’ll be there.” He said, “Come by and see me.” We stopped at the house and he told me about the cable system again and how they had just purchased Cambridge System and they needed a technician there and he thought I’d be perfect for the job. And so I said okay, I’d be interested. And so he called Mr. Stevanus up in Sugar Creek. It was Thanksgiving Day and Steve said yeah, he would like to talk to me so I made arrangements to talk to him on Friday. And sure enough, we hit it off pretty good. We were off like $10 week in salary to start and he said he’d talk to the board and make sure that they’re ready to hire me and he was going to call me back on Sunday. In the meantime, the guy that ran the RETS school had promoted — or not promoted me, but recommended me to two other companies that were looking for electronics people and they both had offered me jobs that weekend. And Sunday came and he hadn’t called and I figured well, they don’t want me. And my wife was out of cigarettes and I went over to the store to get cigarettes and almost blew it because he was only going to be there for a short while and he was taking off for a weekend or a week or something and I needed — had to talk to him that day. We didn’t have much time to — my wife and I didn’t have much time to discuss the jobs and I thought boy, this is something new and I’d be getting in on the ground floor and who knows what could happen if I’m on the ground floor.

SCHLEY: And, Wally, I’m curious about that. What did television look like then and why did you think there was promise in this medium?

SNEDEKER: Well, the pictures in Coshocton were terrible before the cable company came. You couldn’t see it. It was snow mostly. And I thought if this makes the pictures better, you know, that’s a good business because people were loving — if you gave them one channel, they were happy. In fact, early cable systems, some of them only carried one channel. Plus, the TV dealers were anxious for us to come because we could sell — they could sell TVs. But I liked the television. I thought it was great and I thought this is going to be a future. And although we were working with stuff that we’d never worked with before and you had to sort of make your own tools and you had to solder cable together instead of using fittings, it was pretty wild. And everything was up on a pole and you had to learn to climb poles, but I was happy.

SCHLEY: What I meant to ask, Wally, is in the early days of cable you sort of invented it as you went along, right?

SNEDEKER: Right.

SCHLEY: Nothing was set in stone at this point so you had to be an inventor, you had to be a tinkerer, you had to be a messer arounder, and you were, right?

SNEDEKER: You did what it took to make it work. In fact, just antennas, for example. We didn’t know that we would have co-channel interference. We put up antennas, we’d wonder what’s wrong with the picture? Fortunately, we had, Jerrold [Electronics]had ran into it before and told us what it was. So now you’ve got to put up more antennas and screens on the back of antennas to keep out that other channel that was interfering and so you sort of had to remake the antenna.

SCHLEY: And what were these channels? You were retransmitting over-the-air television for the most part, right?

SNEDEKER: Yeah, that’s why they called it community antenna television because we were sort of helping people in these valleys to get television. The main reason we had no signal was because the television signal travels in straight lines and there were hills between us and the television station. So that’s why they would always put the antennas up on a hill and then run down to the city. In fact, Claude Stevanus, he was a true pioneer because their first cable, they put the antennas up on the water tank in Sugar Creek, Ohio, because that was — the water tank’s usually the highest point in town. And it picked up Cleveland stations and they brought them down into the hardware store where he managed a hardware store. He sold televisions, he couldn’t sell …

SCHLEY: They’re showing off this new medium of television, right?

SNEDEKER: Yeah, couldn’t sell them because they couldn’t get a good picture.

SCHLEY: How did you rise in the ranks to begin to take on more than just technical work, to be in the general management domain?

SNEDEKER: I’d worked at Cambridge for a year and Steve, they had the franchise for Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania so he asked me to go to Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania and be the chief technician and build the system. And there again it was an innovative thing because it was — we distributed signals on channels seven through 13 which nobody had done. And I was there and the general manager was Ray Leporati and chief engineer and it was his design of the high channel distribution that made that system possible.

SCHLEY: Why did we want to use those channels? What was the point of messing with what we called the high band at that point?

SNEDEKER: Because if you’re in an area where they’re getting some signals you want to give them as many signals as you can. So if you just use the low band, you can only use — at one time you can only give them three channels. We figured out how to lower the sound carrier so you could run adjacent channels. So we were giving them five channels and that still wasn’t enough so Ray thought we could do this high channel distribution and we used actually headend equipment on the poles. They were strip amplifiers and the boxes were like four, five feet long and two feet wide.

SCHLEY: How do you shimmy up a pole with this trunk on your back? I mean how did people do that, you know?

SNEDEKER: Well, by that time we — they let us put steps on our poles where we had amplifiers and we had to have patent steps on the bottom up 10 feet so people wouldn’t be climbing the poles.

SCHLEY: Oh my gosh.

SNEDEKER: You’d snap them on and then we’d climb the poles. Plus, we had 28-foot ladders that we could use to work. And that’s what we had been doing in Cambridge.

SCHLEY: Wally, what did you learn? What were you learning as you went through this odyssey that you would then apply to your career?

SNEDEKER: Just every bit of cable. Because I was involved in installations and the headend work. We built our own headend building. We bought a steel building and put it together and we put up our own tower in Beaver Falls. And we figured ways to rope these boxes to get them up on the pole. And we built our trucks inside so we could have our equipment in there and we used two men technicians at that time. And we used — we built a cable to run from the — that we’d take up the pole when we went up the pole to service it and we had an intercom in there that we built and we’d talk back and forth to each other from the truck to the pole.

SCHLEY: What I find fascinating about that is this kind of activity was going on community after community as you guys built, you really did, you built the cable industry. Did you know kind of the gravity of what you were doing or were you just trying to get through the day, you know?

SNEDEKER: I eventually figured this is a great, great thing, there’s going to be more coming. I even envisioned putting cable in the house free for the local channels because we had so many other things to sell, but we never got to that, but close to it. You could buy the local channels at a lower rate and once you had it in the house it was good to have it in the house and you could sell them other stuff.

SCHLEY: Do you remember what you charged for cable service back in the day at Beaver Falls?

SNEDEKER: Our early Cambridge systems had a — they charged $125 to install and $3.50 a month. And when we got to Beaver Falls, they were going to charge $90 and $4.50 a month. And we got to talking about it and there seemed to be a resistance to that so we charged $10 install and $5.50 a month.

SCHLEY: That was a better ratio or a better formula?

SNEDEKER: Yeah, you’d get more — and Beaver Falls was funny because when we went there, there was only two channels in Pittsburgh. Beaver Falls is like 30 miles north of Pittsburgh and there were only two channels, channel three, which later was channel two, and channel 13. Three was CBS and 13 was the PBS station. Channel 11 was in some kind of a disagreement with owners or something and they were having trouble getting it started. But lo and behold, before we got our system built channel 11 came on the air in September of ’58. There was another channel that was authorized for Pittsburgh, channel four, but they couldn’t put an antenna up in four because of the co-channel interference it would make with other cities. And so that was embroiled in some kind of lawsuit and stuff like that and finally somebody said, “If you put the tower in the southeast most corner of Allegheny County you can have it.” So —

SCHLEY: There you go.

SNEDEKER: And it couldn’t be up on a hill.

SCHLEY: Wally, another subject. Not everyone in cable was a believer in local origination programming. You were in a couple of different stations in your career. First of all, can you explain to our audience what local origination or LO even was and how you embraced it and brought it into your operations?

SNEDEKER: We were like a TV station. You had your own cameras and production facilities and you had a channel that you devoted to local origination where you would have maybe news programs or interview programs. It probably never got as good as a TV station, but we did a lot of stuff. Actually, in Beaver Falls I may have been the first one to ever do a live basketball game.

SCHLEY: Nice. Like high school basketball?

SNEDEKER: Yeah. The Beaver Falls High School, they were playing another school and they had a fight after the game was over so the school came to me and said, “We’re not going to allow any audience for the basketball games until we get this straightened out. Can you broadcast the game on cable?” I’d already been videotaping it and playing them back, which was another local origination thing. You did a lot of sporting stuff. So we only had one camera and it — nobody was doing that stuff. Maybe up in Meadville [PA]. But the camera was — you had to turn the lens on the front of the camera to get closeups or long distance, you know? It was really crude.

SCHLEY: Yeah, doing a basketball game with one camera is not for the faint of heart, I will tell you that.

SNEDEKER: Yeah. So we did that and it went over pretty well and they just did it for a couple of games until they realized how much money they were losing on the gate.

SCHLEY: But you know, what I thought was neat about it, it was so hyper local. It really took advantage of cable being a subset of the big broadcast station contours. You could do interesting really local programming, right? If you put your mind to it.

SNEDEKER: Back then we put in feedback lines back to the bottom of the hill from where our antennas were and we could put in signals there on channel three. We used channel three. And we had a camera with the weather dials on it and then had the menu board at the end of the camera run and you could time it to stop there if you wanted to have them read a message. And I’d always put messages up there or advertisements or I’d actually talk there about something if I wanted to tell them something. But that was local origination. It was probably the first local origination.

SCHLEY: Excellent. It’s a great example.

SNEDEKER: And we ran a feedback line down to the radio station and we actually put a camera there so that they could do their news on line. It was live video. They were just an FM station. We let them do a live news show on cable.

SCHLEY: Yeah, you could get creative, right? You could do whatever you wanted to do. So I think it’s an interesting adjunct. What — then just take us through your progression, your career progression from that point forward. What was next for you?

SNEDEKER: In 1961 Ray Leporati who was managing and he lived in Cleveland, Ohio and he couldn’t spend all the time in Beaver Falls anyway, but they had started another company called Tower Communications which they did master antenna systems and closed-circuit television systems and hospital systems, all kinds of electronic stuff, TV sales and would do motels with — put the TV in, the cable system in, all at one time. And we really weren’t that busy in Beaver Falls so they said, Stevanus asked me if I’d like to be manager there and I said sure. But I’d seen a lot of things that were going on that if I was manager, I would not do the same. So that helped us grow. We didn’t grow very fast because when those other channels came on the air, we had too much competition from the broadcasters. But during that time, they had the distant signal problem where if you were in a top 100 market you couldn’t bring in distant signals and they considered the Youngstown station a distant signal. I argued with them and proved to them that it wasn’t a distant signal, that their signal strength was greater than the Pittsburgh signal strength. And they allowed me then to carry the UHF stations from Youngstown. If we would have lost them it would have been pretty rough until satellites came because —

SCHLEY: Yeah, and it’s interesting because the whole distant signal regulation was really designed to protect broadcasters. I mean as a cable guy you were up against a lot of forces that didn’t really want to see you succeed, you know, early on.

SNEDEKER: We didn’t get along very well for a while. (laughter)

SCHLEY: Yeah.

SNEDEKER: But then from there I managed a system and I did a good job managing it and in 1969 Paul Snyder came over to my office. He was the director of systems then, the job that I was about to take. He asked me to come to Coshocton and train to be director of systems because Mr. Stevanus was going to retire and he was going to be president of the company. So I said, “That’s great, I’ll do it.” And this was my hometown and it was fun to go back as a success and the manager of the cable system there. So that’s how I got back to Coshocton and then I directed all the cable systems, although I wasn’t the manager of the systems. I just did everything that had to be done to keep them operating and I came up with different ideas and things like that to make them all uniform and started a fleet program where we monitored the fleet and I purchased all the vehicles and started a safety program. Started a universal operation so everybody was operating about the same and we were all using the same paperwork.

SCHLEY: Wally, for you, whether it was fleet management or symmetry of operations, were they just sort of intuitive logical ideas that you thought would be best for the business, or where did those ideas come from?

SNEDEKER: I knew we were having — everybody was buying their own vehicles and they weren’t getting the same design and all stuff like that. So I had friends at the telephone company and — which was unusual. (laughter)

SCHLEY: Yeah.

SNEDEKER: And that’s another thing I did in Beaver Falls. I was able to get the telephone and power company rates for pole usage to a good rate. I evidently — I can’t remember what I did now, but I think I sent letters to the public utilities commission and all that. And finally, they agreed to charge me — that they wouldn’t charge me any more than they charged each other. So that worked out, but so I went to see the fleet manager for Ohio Bell Telephone and he was very generous and sat down with me and he told me how they managed the fleet and how they bought the fleet. So I got some information from them that I used at Tower.

SCHLEY: You must have been a persuasive person because you’re right, these industries, broadcasting and telephone and cable, weren’t always the best of friends back in the day.

SNEDEKER: No. They even brought — the telephone stations in Pittsburgh even invited me to their grand season opening when they had these galas before the new season started.

SCHLEY: Right. Well, when I look at your bio one common thread is you really did, wherever you were, sort of insert yourself into the community. You were a volunteer, you served on a lot of boards. That’s a great thing to do as a human, I get it, but why was that important from a cable management standpoint?

SNEDEKER: Because people didn’t know about cable and the more people you could talk to about cable and be viewed in the community, here’s Wally Snedeker the manager of the cable system. But when they asked me to be manager at Beaver Falls it just so happened they were giving a Dale Carnegie course at that time and I’d never managed anything like that so I thought I’m going to take the Dale Carnegie course. So that really helped me a lot. But when I left Beaver Falls, I was on the mayor’s advisory committee, I was first vice president of the chamber of commerce, I was first vice president of the Rotary Club, and president of the volunteer fire department.

SCHLEY: Well, I think it probably helped in your relationships.

SNEDEKER: I always felt — one of the other things in the community was that you got to be friends with all the other media and I always tried to be friends with the radio station and the newspaper and the TV stations. And in Beaver Falls I was particularly friends there and they — I was even doing a column in the newspaper on TV to advertise what we had on TV cable rather than on the air, what they couldn’t get on the air. And I was always able to convince them to include the channels that we carried in their TV listings which people normally wouldn’t get unless they used the newspaper, but the cable customers that used the newspaper would —

SCHLEY: Yeah, and I think it was important to have good media relationships, right? For the business.

SNEDEKER: I knew the president and the editor of the newspaper well. I actually wrote him a letter to the editor when I left Beaver Falls thanking him for all the good times we had together and how well they worked with my cable system. When I left there people thought I had owned the cable system. I went back — I was back there a year later through the system because a car carrier that was parked on 19th Street, it was sort of a little hill, there was a Pontiac dealer right next to it around the corner and he always unloaded in the alley. So he had parked on 19th Street and we were down at the bottom of 19th Street. Well, while he was in negotiating getting rid of the cars the brakes let go on that thing and it came back down the hill and crashed into our office. I had left there and the manager I had hired, Bob Drogas, was there and fortunately he wasn’t in his office when it happened because it demolished the manager’s office and ended up against the counter of the business office.

SCHLEY: Does the life of a cable guy, like you know, it’s not enough to do customer service and amplifier modifications, you’ve got to deal with somebody crashing into the face plate of your business. That’s crazy.

SNEDEKER: Yeah. I had to go to Beaver Falls of course.

SCHLEY: Where did you go after you left the Beaver Falls operation then?

SNEDEKER: Then went to Coshocton as director of systems.

SCHLEY: Oh, that’s right, okay.

SNEDEKER: And I was there for nine years and when CPI bought the cable systems, they wanted Stevanus to stay on as regional manager. They didn’t want him to retire. They wanted him to stay on so he agreed to stay on so that left three of us managing for a while and they finally promoted Paul to Hartford, Connecticut where he worked in that — managed that system for a while. And it was just Steve and I then for the rest of the time. During that period Bill Arnold was my go-to at CPI and he was the one that would come to the system and we’d talk about things.

SCHLEY: Kind of a legendary figure, right?

SNEDEKER: Yeah.

SCHLEY: Tell me about Bill and kind of your relationship a little bit.

SNEDEKER: I’d actually been in cable longer than he had, but he was a good guy and smart guy and he was more of a money guy than he was a cable guy, but we got along well. And I remember he called me up one time and said, “Wally, I’m going to be there. We’re going to have to go around and change all the franchises to CPI.” He said, “I’m flying up.” So he rented an airplane to fly him up to Coshocton and we flew around to 19 systems and got all the franchises changed and man, I was glad that was over because it was a small plane and he didn’t fly very hard going from these short distances and it was bumping up and down all the time and I thought man — it’s a wonder I didn’t toss my cookies, but we got to know each other pretty well on that trip.

SCHLEY: I’m not sure everyone in our audience realizes, but you had to have permission from each city and town where you operated. We called it a franchise, right?

SNEDEKER: Yes.

SCHLEY: And so when you changed ownership you got to change franchises.

SNEDEKER: Yeah.

SCHLEY: Wally, a big theme in this industry forever, but especially in that era, was customer service. And I can’t resist talking to you and not asking you about an experience you had in Springfield, Illinois. Can you talk about — you inherited, let me just say, a kind of a troubled system. What was that all about?

SNEDEKER: When Times Mirror had purchased CPI and they did away with the Coshocton office so they had — they gave me the Springfield office to manage. At that time, it was their largest system with — I think we had 37,000 subscribers, but they had had five managers during the time of that system operating. It just didn’t — they couldn’t get it to work right. So there I was and they didn’t even tell me it was a union system until I got there. I might not have gone. (laughter)

SCHLEY: Right.

SNEDEKER: But the plant was union, the office was not union, so that was a little nice there. But anyway, I just told them my story and told them what I thought was how to operate a cable system and how to — that customer service, that your customer is always right. They would — a customer would call up and said, “I didn’t have service for five days.” And the customer service representative would say, “We’ll have to talk to the technical department and find out if it was really out during that time” and all that. And I said, “No, don’t do that.” I said, “I give you permission to give them up to five days credit anytime. Don’t argue with them. Just say what can I do to help you and give them that credit if they want it. You’ll spend more time and cost me more money figuring it out than what the five days is worth.” And so they liked that. I also — we did training of the CSRs on what problems they have with cable TV so that when they were talking to the customer, they might be able to stop a truck roll just by what the picture looked like. And things like that. I gave parties for the employees. I said if we reach a certain goal, we’ll have a celebration and I’ll cook. What I did, I delivered in pizza.

SCHLEY: Okay. (laughter) All right, you — part of this was you really instilled more of a sense of pride, you know. I know that prior to your arrival nobody wanted to admit they were working for the cable company, right?

SNEDEKER: Right. Well, when I went there, they said don’t — get an unlisted telephone line and don’t put your phone numbers on your business card. And I was there a while and it was a funny story. I got a phone call at night and this guy said, “Cable?” “Yeah.” “You don’t sound like Cable.” (laughter) I said, “Well, I’m the cable manager.” And he said, “I’m looking for Joe Cable.” They gave the phone number that Joe Cable had.

SCHLEY: I love that story because you kind of were Joe Cable in a way.

SNEDEKER: Yeah. (laughter)

SCHLEY: I mean you were the face of the cable company. You mentioned Times Mirror, one of a number of big newspaper companies that bought their way, you know, into the cable business. At some point they introduced their own pay TV service. It was called Spotlight, I believe.

SNEDEKER: Right.

SCHLEY: And it was a competitor of HBO. I would just love to hear you talk about that episode and kind of what happened and how you were involved.

SNEDEKER: Well, it actually wasn’t a competitor of HBO. They took HBO off the air so you weren’t competing. I was in Springfield then and they convinced me that it was a good thing and they sold me on it before they put it on so I would be a good salesman. And I went to all kinds of trouble. I got Spotlight novelty things like mirrors and flashlights and cigarette lighters and stuff like that and when it came for the launch date, I even had these big spotlights in front of the office going. So I did everything I could to launch it properly, and people complained. I was on the radio, I was on TV, they’d come and talk to me about it on TV. And this one guy, One Eyed Jack, had this radio program where he’s one of these guys that would take up a cause, you know, so he was bad. He was bad. And before it was over, we were good friends and even, they had the [state] fair there in Springfield, it’s the state capital, and he was going to go golf with Willie Nelson when he came to town and he wanted me to golf with him. Well, when Willie got there, he was just too tired and so we never got to golf, but that’s how close we got.

SCHLEY: That’s — but you managed through that, right? And ultimately you guys returned HBO to the lineup?

SNEDEKER: Yeah. We did sell some Spotlight subs.

SNEDEKER: Yes.

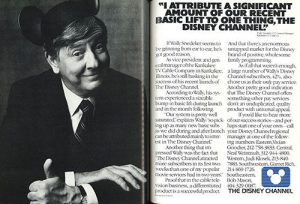

SCHLEY: What was going on in the industry that led people to think you could sell multiple premium services?

SNEDEKER: They had launched the satellite in 1975 and started putting more services on that were — you couldn’t get over the air so it made cable more valuable if you could get them on the cable. And I’d actually left Times Mirror. Springfield then had gone to Kankakee Cable in Kankakee, Illinois. It was a multimedia company that they needed somebody there that could manage and they wouldn’t have to worry about it. They just let you run the cable company and it paid me a lot more money than I was making in Springfield so I went to Kankakee. And while there I had launched a seven-channel tier and rebuilt the system and along came the Disney Channel and I thought I’m going to launch that as soon as it comes on because I think it’s going to sell. And the regional rep for the Disney Channel, I spent a lot of time with him, and he come down one day and he said, “You’ve done a good job with Disney and they want to do a promotion and they’re looking for somebody to talk about cable in the trade press.” They made arrangements for me to go to Chicago to this big photographer. They were like on the seventh floor of this building. I got there and the electricity was off. I had to walk up seven flights of stairs to get there and there was no air conditioning and they had bought me a suit. They wanted a particular color suit and a particular color shirt and tie and this shirt and tie and the jacket fit fine, but when I went to put the pants on, they wouldn’t fit around the waist. He says, “We’re just going to leave the pants on you’ve got on and we’ll just get you from the waist up.” So that went fine. Soon the electricity came back on and it was much better.

SCHLEY: I remember. I worked for Multichannel News at the time and I remember the advertisement and again it testified to this very vibrant era of programming where people were inventing new channels, you know, by the week, it seemed like.

SNEDEKER: Yeah, we were a charter launch, when it first came on. So that was another reason for them to get me to do that, yeah.

SCHLEY: And did it sell? Did it meet your expectations? Was it a hit?

SNEDEKER: It was fine. It worked fine, yeah. I was happy with it. And I enjoyed the popularity of being in the trades.

SCHLEY: Sure, yeah. You mentioned Bill Arnold, Wally, and I just want to throw out, who else was sort of — and Claude Stevanus. Who else were figures in your career that were influential for your life?

SNEDEKER: Yes, my future stepdad, he sort of taught me the value of working hard. He never owned a car. He walked every place he went and I’m always amazed at that. He just, he didn’t want to have a car. He had a driver’s license because he had to drive a pickup truck around to deliver stuff and pick up stuff, but when I was in Beaver Falls Kip Fletcher gave me a lot of help.

SCHLEY: Who was Kip? The name is vaguely familiar.

SNEDEKER: Engineer for Jerrold. And at that time, we were big on Jerrold and you had sort of a contract with them and the engineers would come in and actually Ray Leporati had been a former Jerrold engineer when he came to work for us. Ray was a big influence because he was a smart guy and we did a lot of innovative things there also. They had background music back then which was called Muzak and it was all telephone wired and all that. An FM station in Salem had put background music on one of their — on their band, in their band, and were able to transmit it over the air and they came to our cable system and wondered if we would like to pick that signal up and put it on the cable and sell it to people. And we didn’t have equipment for that so Ray designed the schematic diagram of how it would work, I went to Pittsburgh and picked up all the parts we needed, and built a bench, workbench. We weren’t too busy then anyway and I had all the installers and technicians, I trained them to be manufacturers or builders. So they soldered, drilled holes in chassis and soldered the tube sockets in and all the parts. So we sold background music and then we also provided those for the other cable systems that picked up that signal and put background music on.

SCHLEY: You know, that story to me is emblematic of there really was this kind of — it reminds me of what you did with the high band signals earlier. There’s kind of this willingness to be entrepreneurial in this industry that you and others took advantage of. Is that a fair read on things?

SNEDEKER: Yeah. Again, what I liked early on was everybody would talk to each other. If I had a problem, I would call like Jim Duratz up in Meadville, see if he’d had that problem. And other people. I had met all the other early operators in Pennsylvania because I was on the Pennsylvania TV Cable Association. And so went to meetings and trade shows.

SCHLEY: And there was this exchange of ideas. It was a pretty freewheeling industry. I want to take you to Florida in a second, but I first want to ask you a fun story. We’re about a few days removed from whatever Super Bowl this was in February of 2022 and I saw a commercial with Joe Namath on the television. And Joe Namath actually, the former New York Jet hero, has a little bit of a role in your life. Can you talk about that?

SNEDEKER: He’s from Beaver Falls and when I went to Beaver Falls, he was in high school and I didn’t have much connection with him then, but I had connection with his father. His father just lived a block away from the cable office and we got to be friends and he would come up and we’d talk about Joe’s progress and how good he did the previous weekend or whatever. Then he went to Alabama and he continued on with that and then into the pros. And one day Joe, after he was a Jet, he called me at Christmastime and he wanted me to connect all his siblings to cable because they all lived in Beaver Falls. He said, “I want to pay for it and get them cable. They don’t have it.” He wanted to make sure they could see him play football, I guess.

SCHLEY: That’s awesome.

SNEDEKER: I did it.

SCHLEY: And, Wally, let’s do, if we can, move to Florida. Why did you move to Florida and what was that part of your career all about?

SNEDEKER: I was working in Kankakee as the general manager there and they decided to sell all their holdings. They sold their radio stations and their cable systems and McCaw Communications bought. And I was making a pretty good salary and I don’t think they thought that they needed to pay somebody that much because they had other people who would work for less. And so they furloughed me and I was looking for a job. And Bill James, who was at Cable Systems in the New England area, needed somebody to go up there and manage the systems for — first he told me six months, but it turned out to be like 10 months. He was trying to sell the systems and in order to sell the systems he had to put in a microwave system to get to all the systems and have them all have the same channels. And so I went to Springfield, another Springfield, in Vermont and I did that for Bill. And when the sale went through then I was looking for a job again and so I did some consulting in South Carolina at Anderson. I had interviewed with Frank Schurz at Schurz Communications for a Florida job and I hadn’t heard from him for a while and I thought I didn’t get the job. So I took the management job in South Carolina just to run those systems and all of a sudden, I get a call from him and he wanted me to go to Atlanta and interview with a psychologist there that they use for all their management people.

SCHLEY: Oh. (laughter)

SNEDEKER: I’d never done that before. And it so happened that the test that he gave me was a test that I had used back at Tower to hire my management people. Because they put me in charge of hiring people at Tower. They needed a manager. And I’d always give them this test. It was the same test I gave them so I knew a lot of the answers so I (laughter). He says, “You’re the only one ever finished this test.” (laughter) And but he was — he asked me things about what could I tell him about him. You know, just being there with that brief time and I guess I figured out a lot about him then while we were talking so I told him. He asked me a lot of questions. Next thing I know they offer me the job in Coral Springs, Florida. And I wasn’t too happy in South Carolina. Two weeks after I got there the chief technician was killed in an automobile accident. So that made things really bad. So I went to Springfield — or not — Coral Springs. Too many towns.

SCHLEY: Too many springs, right?

SNEDEKER: Went to Coral Springs and they — it was a good system. The previous manager had done a pretty good job and he’d gone to work for Jones in a bigger system. So I liked the city and I liked the temperature and I liked the employees I met and I had — there was a chief engineer there that I liked and a marketing manager I liked. Rick Scheller was chief engineer and Michelle Fitzpatrick was the manager of marketing and I could see we could hit it off right away.

SCHLEY: And, Wally, by now this cable industry looked very different, right? From the cable industry that you started out. What were some of the signature advancements that you saw and managed in Florida?

SNEDEKER: We rebuilt the system so it was the top level. And of course, we had two-way equipment and all that stuff. And they were coming out with pay per view and so we jumped on that right away with Scientific Atlanta and we had the addressable boxes. And we sold pay per view which was good. We did the fights and things like that and also movies. Then I saw the internet possibilities and so we started — built an internet in Coral Springs where we provided internet service.

SCHLEY: And this would have been in the ’90s, the mid to late ’90s, is that right?

SNEDEKER: I started in ’88 and worked to ’99. So we had put the internet on some time, I think, in ’98. We finally rebuilt — I rebuilt a fiber backbone which was like $8 million and upgraded the amplifiers. And we had also purchased another cable system which I had negotiated at Weston, Florida. And so we were promoting, we were doing things better. It was just like I did on all the other systems. Even though they were doing pretty well they still lacked some customer service skills. We improved on customer service skills. I added more telephone lines, which I had done in Springfield also. And I added automated telephone which now some people hate.

SCHLEY: The robo voice?

SNEDEKER: Yeah.

SCHLEY: But it brings up an interesting question. So whether it was turning around Springfield, Illinois or dealing with this operation, what was it that made customer service hard in the cable industry? Was it just the sheer amount of demand that you’re trying to manage? What was hard?

SNEDEKER: You only had so many employees and if something happened you couldn’t answer the phone fast enough. That’s why I did the automated thing and put them in queue. Plus, there again they needed training as to maybe get rid of some of the calls that weren’t a cable problem. And we had — we lost signal just like everybody did. If there was a power outage you would have problems. We went to standby power finally at our power supplies. It used to be that every amplifier had to have a connection to the 110 volts. When they came out with solid state you didn’t need that much power, but we powered through the cable and they weren’t that many — that you didn’t have that many places where you needed the 110 volts so we were able to put a standby power unit at each one of those spots which improved customer service.

SCHLEY: I mean do you ever look back — what we’re talking about in this hour, you’re talking about going from tube amplifiers and trying to eke out six more channels of video to the internet, to fiber optics, to pay per view. I mean it’s pretty breathtaking, right? When you think about what you’ve seen and been involved with over the years.

SNEDEKER: It’s never a dull moment, I’ll tell you. It’s always something coming up and that’s why I liked it because it was a constant challenge. It was just, it was so amazing that people saw the need for these things and developed them and we kept up with it. If you were smart you kept up with it in your cable system.

SCHLEY: Which I think is a great point. What would your advice be to someone who’s coming up in their career or wants to be involved in this, I don’t even know if we call it cable anymore, Wally, but in this industry? What attributes would you look for in a person you were interviewing or considering for a job?

SNEDEKER: You have to be a self-starter and you have to be able to — you have to be over — understand everything that’s going on in your system because that’s the hardest thing there is, to have a manager that doesn’t know what’s going on and is not a cable — you wouldn’t have to be a cable guy, but you’d have to be somebody that could learn and understand everything. I did well because I had technical abilities as well as management skills. So the chief technician couldn’t put anything over on me if he — because sometimes —

SCHLEY: Very good point. You recounted to me in a previous off the cuff conversation a really touching story about a young man we came to know as the bubble boy in popular culture. And I can’t let you go without asking you to talk about that.

SNEDEKER: Okay. That was in Coral Springs, Florida. And one of my installers was out on non-pays, to disconnect customers for non-pay if they didn’t pay, and they went to the house where the bubble boy lived. And she explained to him when he was there that she just had so many bills and just hadn’t got around to paying and so she introduced him to the bubble boy. So he came right back to the office and said, “You’ve got to see this boy, and talk to him and his mother.” And so I did. And you had to put on a gown and a mask and gloves, and he and I hit it off just like you and I hit it off here talking. And I thought well, I like this guy and I’m going to do what I can to help him. So I told them not to worry about the cable bill anymore, that we wouldn’t bill them anymore. And I told him any time he wanted to talk about anything just to call me. I didn’t like going to the house because you had to be so careful with your clothing and everything. And next thing you know he’s calling me on the phone, “Hi, Wally.” I’d given him my private line. And he’d say, “Are you having a good day today?” You know, he never had a good day.

SCHLEY: Right.

SNEDEKER: And but after I’d left Coral Springs, we were retired in New Smyrna Beach, Florida, he passed away. So I didn’t get to say goodbye to him. But he even came to my retirement party and it was a challenge for him to come out of the house. Because he was in this wheelchair device that had all his oxygen and his masks and everything to keep him from getting into contact with germs. He couldn’t get, he was — you know, it was one of these immune diseases.

SCHLEY: That’s amazing though.

SNEDEKER: He took the microphone and talked to everybody about me, how — what a good friend he was — I was to him and all that. So that made me really proud, I tell you.

SCHLEY: Well, and this is not as weighty of a topic at all, but I did want to ask you about one more operational subject where for a long time signal theft was a big problem in the cable industry and different ways to attack it technologically. But you were a pioneer in something we called an amnesty program. Could you just talk about what that is and why it mattered?

SNEDEKER: Well, a lot of times it wasn’t always the customer that caused the problem. It was technicians or installers that wouldn’t disconnect them and they’d continue to watch TV. What I did, I started auditing my cable systems, physically auditing them. I found a lot of illegals. I had an advertising program that we were going to proceed with doing, you know, getting them to jail or whatever it was if they steal the cable.

SCHLEY: Right. (laughter)

SNEDEKER: And it was an advertising campaign as well as it still brought cable to mind in that the people that were paying were happy to see that because we were making other people pay for the cable service too. And it brought in a lot of subscribers.

SCHLEY: So it did. It worked to shore up at least a little bit that problem. Wally, this is a big question because you’ve been in this industry since the mid-1950s all the way to the internet and fiber optic era, but what are you proud of in your career? What would you point to as I made a difference, I mattered? What comes to mind?

SNEDEKER: Maybe a couple of my kids for one thing. Craig followed me into the business and Don Matheson hired him at Media Journal in Washington and he went on to Comcast and became a star manager for them. And he actually left Comcast and went into my first business which was meters. Worked for a company that made meters for power companies and did power management. And so he went into cable. One of my other — my stepson Matt, he went to work for a company that did billing in Atlanta so he got into cable. And he worked for another company that provided materials for cable. So those two kids. Plus, everybody was interested in it. My daughter used to want to ride — if I had to go to the headend on a weekend or something to do something she’d say, “Can I ride along, Daddy?” So she’d go with me in the truck and we’d go fix what was wrong. But I think mainly I was a good guy. I didn’t — I made people do their job. If they didn’t do their job, I fired people that were difficult. And when I was in Kankakee, I filed a suit against one of the electronics repair guys because he was building cable boxes. We actually raided his office and went to trial and he was convicted of cable theft. But he was selling cable boxes to people which they would get their channels free.

SCHLEY: Yeah. Well, I mean you must have hired and sparked careers of hundreds of people, I’ve got to believe. I mean that’s a long stretch and this is a person intensive business so my guess is you touched the lives of a lot of people.

SNEDEKER: I did. And I promoted — I always wanted to promote from within if we had an opening so I would promote a technician to chief technician. I’d maybe promote an installer to a tech position. And we never promoted anybody to manager. We tried a couple of times, but that didn’t work. But I hired most of the managers that were working for Tower Communications. When I left, I had hired most of them myself. So they’re still — they were still there. Of course, I’m probably the only one still around.

SCHLEY: Well, you know, I always felt that the cable industry draws on a lot of talents from a lot of different disciplines, technology, finance, engineering, but the general manager, you know, community after community, really is kind of the heartbeat, I think, of this industry in so many ways because you had to do everything. And to be able to kind of just chat with you for the last hour about taking us from the early days of over the air transmission to the modern era has been an absolute delight. So thank you very much, Wally, for spending time with us at the Cable Center.

SNEDEKER: Okay. I enjoyed it and thanks, Stewart, for giving me this opportunity to give my oral history. We could probably talk for another hour.

SCHLEY: I would bet — I bet we could. So Wally Snedeker for the Cable Center’s Hauser Oral History series. Thank you for tuning in. I’m Stewart Schley and I’ll see you next time.

SNEDEKER: Thanks, bye.

END OF INTERVIEW

Addendum

Mr. Snedeker would like to add to the record that his oldest son, Bob, went on to become a chemical engineer and owned his own business. His son, David, has his own business using video technology and made movies. His step-daughter, Sarah, had her first job in cable television and works in digital marketing. Lisa and her husband went on to own their own business in computer technology and are involved in artificial intelligence. His step-son, Matt, owns his own business in digital marketing and management. They all have that entrepreneurial spirit exhibited by Wally in his cable career.