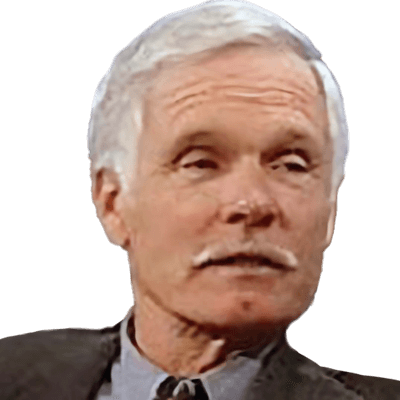

Interview Date: November 28, 2001

Interviewer: Paul Maxwell

Note: 1999 Cable Hall of Fame Honoree

2020 Bresnan Ethics in Business Honoree

MAXWELL: Welcome to the Hauser Foundation’s oral history taping of Ted Turner and Ted was cable before cable was cool, but cable’s cool now. So we’re going to go through this a little bit chronologically, but I want to go back to something that Terry McGuirk was telling me about earlier. Right about the time WTBS went up on the satellite and you were down in Florida, this is about ’75, I think, and Terry talked your way on to the podium to talk about what you were trying to do. But I think you got there and didn’t know quite what you were doing so you started having everybody do calisthenics and I was wondering if we couldn’t start that way here today. Do you remember that?

TURNER: No.

MAXWELL: Terry does. He says you went through 10-15 minutes of it before you thought of what to say. You don’t remember it?

TURNER: I remember going to the meeting but I don’t remember leading the cable operators in calisthenics.

MAXWELL: I think that sort of set the tone for how you approached the industry though.

TURNER: Well, it was a team operation so… And I’d like to thank everybody that came today. It’s really gratifying to have such a nice turnout and also I want to thank you all for helping me get rich and I hope I’ve helped you all get rich too. There was plenty of money to go around for everybody.

(LAUGHTER, CLAPPING)

MAXWELL: You had that little station in Atlanta in those days, and one in Charlotte, I think, at that time?

TURNER: Right.

MAXWELL: And what got you interested in the cable television business there?

TURNER: I didn’t have any money, or had very little money at the time and I wanted to get in the television business and all I could afford was UHF stations and everybody here knows, UHF was pretty hard to receive without cable and the metropolitan areas like Atlanta didn’t have any cable, but there was cable out on the fringes of the metropolitan area and cable had just started in places like Macon and Columbus, Georgia that were about 100 miles away – Huntsville, Alabama – and they were bringing in the Atlanta stations to get a full complement of network stations and I figured, well, if you were in Columbus, Georgia it would be worth as much as one in Atlanta pretty much at some point in time if I could get enough of them. And besides, even in Atlanta I wanted cable there as quickly as possible so people could receive us because it was very hard to receive UHF with a dependable signal. So, at the very beginning I figured that cable was going to be good for me as a UHF television operator so I decided to throw my lot with cable early and then I would provide good programming so that the cable operators in the surrounding area, and later with the satellite all over the United States and then the world, that we would be mutually beneficial to one another and that we’d all get rich together and that’s exactly what happened.

MAXWELL: That is kind of what happened.

TURNER: And have a lot of fun too. I mean, it’s pretty hard to get rich without having fun unless you’re robbing a bank. We didn’t do that. We earned our money the good old-fashioned way; we worked for it.

MAXWELL: Well, good. When satellite came along, what made you jump to that?

TURNER: Well, I saw the satellite as just… In those days we had to do microwave and you had to have a microwave tower every 35 miles because that’s the only way to get there and each one cost $50,000 or $100,000 depending on the terrain. But it was an inefficient way – it was okay to go from point to point to point but it was no good, or not efficient, for point multi-point and when I read about the satellite, the communications satellite, I said, “Wait a minute. This is an antenna 22,000 miles up in space that can cover the whole North American continent and we can go point multi-point to every cable operator in the country and if we put compelling enough programming on that satellite and give the industry something that people will be willing to pay for, then we can get cable operators to start in the major metropolitan areas and we can wire the whole country and have a national medium and eventually we’ll get the 80% penetration and then we compete with CBS, NBC, and ABC and make billions.”

MAXWELL: You thought about all that back then?

TURNER: And that sounded good.

TURNER: And so that’s what we did.

(LAUGHTER, CLAPPING)

MAXWELL: That satellite you picked, do you remember the guy that came in to sell it to you?

TURNER: Nobody came in to sell it to us.

MAXWELL: Oh, you called…?

TURNER: We had to call. We had to call just about everybody. Very few people came to see us in those days and even the people that we went to see… It was a guy from Western Union, what was his name?

MAXWELL: Ed Taylor.

TURNER: Ed Taylor from Tulsa, Oklahoma. Ed, if you’re still alive out there, hello. Anyway, I called him and I said, “I want to come up and find out about the satellite.” I said, “I want to use the satellite to cover the country with my television station down here.” And he said, “Well, come on up.” I think I landed at Newark Airport and they sent somebody to pick me up and take me down to Western Union’s headquarters and we spent an afternoon going over, you know, showing me around and how things worked. I already knew basically how it worked, but I wanted to establish contact and get them to start negotiating to run a transponder so we could get on the satellite.

MAXWELL: But you didn’t go onto Western Union’s?

TURNER: No, because Ed was in the process of leaving Western Union to go with RCA, SatComm, I think, or whatever it was. And HBO was already on… well, actually that’s not true. At the time I went to see Ed Taylor, HBO was on Western Union because the Western Union satellite was the only one that was up and working. RCA was in the process of getting ready to launch their first communications satellite and HBO had already made arrangements to switch over to that satellite and it became very clear that we wanted to be on the same satellite with HBO. There were only going to be two services up there to start with but it would be much more cost efficient for the cable operators if we were on the same satellite because one satellite dish would receive both signals without adding a second dish. In those days, satellite dishes… Bob Rosencrans bought the first one down in Florida, as I think everybody remembers, and it cost close to a hundred thousand bucks, which was a lot of money in those days for most of us.

MAXWELL: Now it’s not?

TURNER: No.

MAXWELL: So you got up on RCA and you had WTBS up there, but you weren’t really allowed to go sell it, were you?

TURNER: We were not allowed to rent the transponder ourselves either, it turned out when we checked with our Washington attorneys. And remember, this was all new stuff so when we’d go to Washington and ask the FCC about things, they didn’t have any rules about buying satellites, running satellite transponders, it was too new, so we had to kind of invent everything as we went along. But every problem that there was, I’d go to bed at night and think about what the problem was and almost invariably before dawn I’d have a solution to the problem, at least a theoretical one, and we’d go out that next day and try and solve that problem and then before the day was over a new problem would arise. Everybody here that was building cable systems and getting franchises in those days, they know what I’m talking about. We had to write the rules as we went along because we were doing something that nobody had done before. We were like Christopher Columbus, when he left Spain to see the New World, he didn’t know where he was going when he left, he didn’t know where he was when he got there, and he didn’t know where he’d been when he got back.

(LAUGHTER, CLAPPING)

TURNER: And we call him the father of our country.

MAXWELL: That started those southern satellite systems, those came out of that. It was one of the solutions, right?

TURNER: That’s right, and I gave him the right to put us on the satellite and I said, “Look, if you charge ten cents a month and you get a million subscribers, you’ve got a hundred thousand dollars a month and the transponder costs a hundred thousand, so you break even with a million subscribers and from there on, every dime you get a month…” You know, a dime a month doesn’t sound like much, but if you get enough people, you know, you can get rich. Every month, you know, year after year.

TURNER: And besides, you start at ten cents and then go to twenty and thirty. That’s the way cable started, at 8 dollars a month and then we got it up to 40 bucks a month. That’s where the money is when you get more later down the line when you’re providing a more valuable service.

MAXWELL: So TBS then grew across that five years from ’75 to 1980 and you got a hair to go start a news network. But you weren’t known for news back in those days.

TURNER: Well, I couldn’t afford news. Basically there wasn’t any point to me promoting news before I decided to go with CNN because it wouldn’t have been in my best interested to do so. And besides, I thought the news was pretty negative anyway and pretty biased, so I didn’t watch it very much. Not television news. I watched it a little bit but I didn’t want Walter Cronkite telling me how to think. I mean, I like Walter Cronkite, he’s a personal friend, but in those days he used to give his opinions all the time on the news and I didn’t like it.

MAXWELL: So you started Cable News Network.

TURNER: Umm hmm.

MAXWELL: And why did you call it Cable News Network?

TURNER: Well, I figured there was a lot of skepticism by people, some of whom are still in this room. The great thing about the cable industry is most of us were here at the beginning and we’re going to be here at the end too, because the endgame is just about here. Within the next year there will only be two cable operators and one satellite operator, basically, and the game’s over because like in Monopoly, when you own all the real estate on the board, there’s nobody else to pay rent, you win. All you have to do – it’s so sad – I was over on the floor over at the convention center today and it looked like Kosovo or Afghanistan, there were so many holes where there used to be people that were displaying their wares and there’s very little left over there. The industry’s going to be part of a big telecommunications industry but it’s not the cable industry anymore. AT&T’s the biggest cable operator and they’re going under, or they’re going to disappear within the next year. Things are happening awfully fast, but it was a really interesting thirty or forty years. It really was.

MAXWELL: It was just 21 years ago that you started Cable News Network.

TURNER: That’s right, but cable had already started about forty years ago.

MAXWELL: True.

TURNER: And the Superstation went up 27 years ago, so as far as I’m concerned I’ve been in it for 30 years and 30 years is a long time, but it’s short – we wired the whole country and basically got the vast majority. 80% of people subscribe to multi-channel television. That includes the two satellite providers.

MAXWELL: But back to Cable News Network – you named it Cable News…?

TURNER: Oh, that’s right. The reason for that is that there was speculation on whether we would succeed and whether we had enough money to see it through and I figured if we put cable in the first name and we were going to promote the living daylights out of it, not with a big advertising campaign, but me going around talking to newspaper editors and everything, that “call your cable operator” and it would have been very confusing for the person answering the phone at the cable company to say, “No, we don’t carry the Cable News Network.” Well, why not? It sounds like it’s owned by the cable industry, why aren’t you carrying the Cable… you’re a cable system. I thought it would be confusing enough to where it would help us get more carriage and it did.

MAXWELL: And it did. In 1980 though, you’ve had a history of kind of betting the ranch, so to speak, in the company and in 19…

TURNER: But only when I thought the odds were heavily in our favor. But it’s pretty hard when you’re doing something that’s never been done before to know for certain whether it’s going to work or not. We took a lot of risks but so did most of the people in this room. When you go into a new industry that doesn’t exist before and you go out and try and do the things that all of us in this room did, we all took risks.

MAXWELL: Not everything worked either. I remember a music channel.

TURNER: Well, that really did work. The music channel did work. First of all, John Malone and some of the bigger cable operators – MTV was trying to get a 100% rate increase for that garbage programming that they had on, those free videos that they didn’t pay anything for, and the cable operators dug in their heels and they needed somebody to leverage MTV. So they said, “Ted, do us a favor and start a music channel and announce that you’re not going to charge any fees and that way we can negotiate a better deal with MTV.” So I did that and we got on the air in thirty days with it. It’s so easy to do and so the cable operators all cut the deals they wanted, MTV reduced their prices back down to very minimal rate increase and we signed off a month later when we realized that we’d served our purpose, but it only cost… I think it cost us less than two million dollars. It wasn’t even a lot of money then, but we had built up a lot of good will on the part of people like Malone and the other big cable operators that felt like they were being screwed by MTV. So they carried our services and there was always quid pro quos to what we did. I mean, it never hurts to be popular with your customers.

MAXWELL: Never, ever.

MAXWELL: When SatComm Three, though, took off, it didn’t quite make it.

TURNER: What?

MAXWELL: When SatComm Three took off? It sort of blew up.

TURNER: Oh yeah. It disappeared.

MAXWELL: Yeah, and you had a little problem there with transponder space.

TURNER: That’s right. We were about a month or so away from starting CNN and we had no place to distribute it. But Terry McGuirk reminded me, and he negotiated this, I think, it’s a long time ago, but we might as well give him the credit, he would have gotten the blame if we didn’t have it.

TURNER: When we rented the transponder, when we rented it there were a lot of cable networks then and they were standing in line to get on SatComm Three, which had disappeared. So now we had probably ten customers – don’t hold me to that number – but there were multiple customers for the two transponders or one that were still available on SatComm Two, which was already up and running. We were pulling our hair trying to figure out what we were going to do because we would have been in big trouble because we had all the expenses for CNN, a lot of them had been committed for, we were already building bureaus and we’d already hired hundreds of people and so forth, and Terry reminded me that when we signed the deal with RCA for the transponder that we later transferred over to Ed Taylor for the Superstation, TBS, that we got an option for an additional transponder. So when we confronted the RCA executives with that, that we had a written contract for a transponder, and we’d really forgotten about it because it was five years before that we did that, and they agreed to give us one of those two transponders.

MAXWELL: They didn’t agree easily, if I remember.

TURNER: No, we had to threaten lawsuits.

MAXWELL: There was a court fight and you had to go to the FCC.

TURNER: We were prepared to go to the mat with them if necessary because it was a matter of our survival.

MAXWELL: And they caved.

TURNER: They did.

MAXWELL: Good. Later, when CNN became successful, it generated a competitor.

TURNER: No, no, it was long before.

MAXWELL: SNC started a year and a half after we started CNN. CNN did not become profitable until its sixth year and we had 250 million in it at that time, approximately, but SNC came long before we were profitable, three or four years before we were profitable, and it really was a dagger pointed at our heart. It was one of the greatest threats. We faced a number of threats over the years, obviously, but it was a formidable maneuver on their part and we were quite concerned about it.

MAXWELL: You eventually acquired them, so their challenge to you didn’t work. Do you remember how that played out?

TURNER: Yeah, of course. Everybody in this room does. I mean, everybody over 50.

MAXWELL: True, but… I think Bill Daniels brokered the final deal with Dan Ritchie when he bought the assets of SNC.

TURNER: I think he helped us.

MAXWELL: He helped you there. But what made Westinghouse and ABC blink instead of you?

TURNER: Well, we started… they were going to take several months and their first network… they announced they were going to do two networks; we only had one, CNN. They were going to have a long form network that would compete directly with CNN, but they were going to start with a short form network called SNC that was going to have an 18 minute news wheel and I thought it would be better to do a 30 minute news wheel anyway, because people were used to turning from one station to another at the top and bottom of the hour because that’s when the networks changed their shows and so I decided we’d try and get on the air before they did and we got on the air and I think four months, 120 days, with our second news network and preempted them a little bit and we split the headline news carriage agreements because cable operators didn’t want to carry two of these channels for the most part and we made them not viable. It also cost us a lot of money to do that but we figured that we had to attack them first, have a preliminary strike, and make them unviable so that they’d withdraw from the battle before they started their long term network and it was all calculated and carefully thought out and it worked to a charm.

MAXWELL: So they went away.

TURNER: Well, they sold out to us for 25 million. We gave them a little stipend to leave the industry and ABC and Westinghouse, we had defeated them. It was like Vietnam beating the United States. Nobody thought we could do it, but we did.

MAXWELL: True, at that time. So, this video they showed of you, the song, “I Was Cable When Cable Wasn’t Cool”….

TURNER: I came up with that at that time.

MAXWELL: It was right around then.

TURNER: It was exactly at that time. I wanted to remind… I think it was the Western Show… It wasn’t the Western Show, it was a national show I think in Vegas because we bought a billboard, rented a billboard, with a cut out of… because I wanted to remind the cable industry not to go with Satellite News Channel that was Westinghouse and ABC because they were the enemy. This was before Westinghouse bought TelePrompTer. They were the competition and they would be making a mistake going with them because I was with them from the very beginning when they really needed help and if they had abandoned me at that time and I hadn’t made it, they would be in the hands of people that didn’t have their best interests at heart, the broadcasters, and most of the operators did stick with us and we never – that’s why I thanked everybody at the beginning – we could not have done it by ourselves. We couldn’t do it without the support of the cable operators, but I do have to say I think we earned the support of the cable operators over the years in giving a superior product at a reasonable price. We never tried, like ESPN and some of the other networks have done, to screw you to the wall. Get the last nickel and then another.

(LAUGHTER, CLAPPING)

TURNER: I figured if we just got a small profit… I decided early on, I said what would be a good split between us and the cable operators. If I get 10% and the cable operators get 90% of the profits from this industry, that would be okay with me. ABC/ESPN wants 50%. They want half your money. I only wanted just a little bit, just a lousy little 10% and if I got that from everybody I could live and get my children through college and that’s what happened, and still have a little left over for retirement, you know.

TURNER: I never thought I’d have to retire but that’s for a later time.

MAXWELL: We’ll get to that.

TURNER: I never thought I’d get prematurely retired, but neither did Trygve Myhren and a lot of people in this room. A lot of good men.

MAXWELL: So you started other networks.

TURNER: Yes.

MAXWELL: You’d started some other networks and TNT came along with… you were line extending what you were doing and using…

TURNER: Like the Cartoon Network, right. I figured the more networks the merrier. By this time, cable operators were figuring the more systems the merrier. We were already on our way towards getting big and consolidating.

MAXWELL: You were one of the first, though, to combine the sports franchise with making it a major piece of programming.

TURNER: By far the first. We bought the Braves ten years before the Tribune Company bought the Cubs. The broadcasters were only 8 or 10 years behind us. Thank God they were so slow to react. It gave us an opportunity because at the beginning… Everybody thinks Bill Gates is so smart and I think he’s smart too, but basically he didn’t have… he had some competition but the field was wide open, the computer software field was pretty wide open when he started. But when we started, the three broadcast networks were thousands of times bigger than we were. That space, the television broadcasting business was filled with three gigantic competitors that were already well entrenched and had been in business over thirty years. So it was very, very difficult but they were so stupid and slow-footed to move that they allowed us to get very nicely established before they reacted. The whole idea in business, I think, is to figure out how to start something new if you can, and if not that, come up with something a lot better mousetrapped and then market the hell out of it and establish your market position before your competitors react and then hopefully you’ve got competitors that are large and slow like dinosaurs like the networks were at the time. But the networks have rallied. I mean, most of the cable programming now is now owned by the networks. It was only a matter of time and basically to get around to the question about why I sold to Time Warner, I’ll explain what the strategy was then. The game was a constantly changing one. It was like playing three dimensional chess and it’s hard enough to play two dimensional chess and three dimensional chess is extremely difficult.

MAXWELL: You had made a run at a network before. A couple of times.

TURNER: At one time or another – this is a story that has not been completely told – I could have purchased CBS, I mean I had it, it was right there; I had a handshake already with NBC at one time; and I had ABC purchased too, or I had a merger… I was a handshake away. The deals were made, but they all eluded me by just… they were right there. I could have been a contender. Remember what Marlon Brando said in On the Waterfront. But I can’t worry about the things I didn’t do. I still made billions and started more networks then anybody else. I’m not going to sit here and be maudlin that my career was a failure because I didn’t get one of the big networks. It didn’t work out exactly like I wanted but I still did okay. I ain’t going to apologize to nobody. That’s right.

MAXWELL: So why did you sell to Time Warner?

TURNER: Boy, we sure passed over a lot of history. There went 15 years!

TURNER: Well, there were a number of reasons. First of all, when we lost the retransmission consent battle, and I suspected all along that the broadcasters were eventually going to win in Washington. They were going to win in Washington because with their local affiliates, they covered the congressmen and senators at election time and they really had a lot to say about who got elected and who didn’t get elected at the state and congressional level and they were going to use their leverage there to beat us in Washington and they did. They eventually did. For a long time we held them at bay and it was all of our effort. At one time I knew half the senators on a first name basis. I spent, like we all did, those of us who were there in that day, a lot of time in Washington. But it was really very, very critical for me that the networks not get control of the cable industry early on before we were established and we were able to hold them at bay for years but then eventually they won the retransmission consent battle and they also won the battle to get the digital spectrum and I knew they were going to eventually come up with, there was a good chance that they would come up with six channels apiece and either through their retransmission consent plus the leverage they had with the government, the elected government officials, that they would force their six channels onto the cable systems. It hasn’t happened yet, but mark my words, it will happen. It will happen. They will get digital must-carry and when they do, that’s going to be… there’s six of them now – you’ve got WB, UPN, ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox – you’ve got seven of them, each with six channels, that’s forty-two channels, that’s half the capacity. But we’re headed into a world where there is going to be virtually an infinite number of channels anyway and this is all part of this because it’s very complex, in a world of infinite channels, or infinite choice, at your fingertips with video on demand, the value of channels goes down and also with the Internet. The Internet is another competitor and so I thought that there was a good chance that over time, and then on top of that, everybody wanted to have a cable network. Cable had the dual revenue stream and I was the one that invented the dual revenue stream. CNN was the first network that came out and honestly told the operators, you’re going to have to pay us 15 cents a month for this network. At that time, if you’ll recall, ESPN was advertising that they were going to pay you to carry ESPN. Ha ha ha ha. Suckers! You didn’t have to look through that one very far to see “you’re going to pay us $2.00 a month” is what they meant, per sub. Anyway, that was one thing. I thought that we had a good chance, well, I already knew with retransmission consent, that’s one of the reasons I desperately wanted a network because I knew we were going to eventually not be able to compete without a network, not to compete at the top level. I did not want to be a fringe player in the broadcasting business. I wanted to be the dominant number one player and we were there. When we merged with Time Warner, Time Warner it was at the time, the overall value of our company was about 12 billion and at that time, the networks were worth six or seven billion apiece. So we had basically doubled the value of what CBS, NBC, or ABC were worth during that 20 year period from 1976 to 1986 when I merged with AOL Time Warner. And one reason I merged with them is AO… it wasn’t AOL… Time Warner’s stock, the value of it, you can figure out what the real value of assets were and the combined value of Time Warner stock was about half the value of what I thought those assets were, the various cable companies, what HBO was worth, what the magazines were worth. I figured they were selling for half of what they were worth and if I could get what I thought was the real value for TBS, which was about 12 billion, and Jerry was willing to give that to me because he was in so much trouble at the time. I figured all we had to do was merge with them. We would be getting double the value that the Time Warner shareholders had and then all we had to do was go out and convince Wall Street that the Time Warner assets were undervalued and they were going to be managed in a more intelligent way than they had been in the past and then the stock would come up to what it deserved to be at, which we would double our stock during the first year and then from then on we could show how there would be a lot of synergies and things would really work and then we could double it again and that would be four times our money, so I just had to do that and it’s exactly how it worked out. We did; we quadrupled our money in about two years, which is not bad. But there was another reason too. I was really brokenhearted when Jerry vetoed – he had the power of the veto and he was on our board – and he vetoed the NBC acquisition. If we had gotten NBC eight or nine years ago when we had it for 5 billion dollars, had a handshake deal with Bob Wright and it was 100% financed, it was really a terrific deal. They were going to take a billion dollars worth of common stock. They said, “We’ll give you some kind of preferred stock that pays a little dividend that we can cash in on and if you can’t borrow the other three billion from a bank, or a consortium of banks, we’ll finance it through GE credit.” So it was a turnkey deal and John Malone voted for it but Jerry vetoed it and I knew then that we couldn’t win, that our hands had been tied behind us. The biggest mistake I ever made, really, and Malone told me not to do it, was bringing Time Warner into the consortium of cable operators for that five hundred and something million that we needed to pay down the debt that we incurred when we acquired MGM. I shouldn’t have done that, I shouldn’t have let them have the veto, but I was tired too. That was the other thing. I was tired. After thirty years of working 18 hours a day, five or six days a week with one crisis after another for twenty years, I was tired. And when you’re tired you don’t make the best decisions and I knew we were selling out. I didn’t know what the consequences would be. I never thought in my wildest dreams that I would actually lose my job. I just couldn’t believe that, but it happened. It happened. So my advice to any younger people in the room is be real careful who you sell to if you sell your company. Be prepared to leave it. If you sell it, be prepared to leave it. I figured, at the time I owned 9% of Time Warner, and I figured, well, Jerry thought that he bought me but I thought I bought them. But 9% is not 51%. Let me remind you of that. My math wasn’t too good. I did pretty well in high school math, but I had forgotten. I guess I just got a little overconfident, but I was tired too and you should never make important decisions when you’re tired. Get a good night’s sleep first. Pretty basic.

MAXWELL: Pretty basic. We could back up a little bit. One of the things that you…

TURNER: Yeah, we covered a lot of ground in a hurry. Hey, it’s hard to do. This was a long history. This was thirty-five years of history that we’re trying to get through in sixty minutes. That’s without commercial breaks.

MAXWELL: We had that at the beginning with The Cable Center. One of the things you accomplished that was amazing to me when it happened was taking CNN around the world. I think it’s one of the most unique accomplishments anybody did. You got landing rights for a signal everywhere and can you talk a little bit about how you managed that?

TURNER: Well, it was a great challenge. Where did the idea come from to cover the world? Well, in 1982 we had already been down to Cuba a couple of times with CNN news crews and Fidel Castro told Eason Jordan when he went down there, who was the guy in charge of international news, he said, “If Turner ever wants to come down here, I’d like to meet him.” So I jumped on a plane and went down there to meet him and we spent all night drinking and smoking cigars and he told met that CNN was just invaluable to him. The signal spilled into Cuba and he read about it or heard about it, maybe the CIA let him know, that there was an all news satellite signal that he could see in Cuba and he said it was just invaluable to him, so the idea just lit up. I said, “If Fidel Castro can’t live without CNN, well, we ought to be able to sell this all over the world.” So the idea really started with a commie dictator, who turned out to be a pretty good friend actually. That’s right. Well, if you’re going to sell your signal all over the world, you’ve to sell it to a lot of – in those days half the world was communist – so we went out and sold it to communists, we sold it to capitalists, we sold it to anybody who’d pay and that’s what the cable operators did. I mean, you know, anybody that had thirty bucks a month could get cable, right? We didn’t care what color they were, what gender, you know, just so long as they paid on time. That’s right.

MAXWELL: You even had trouble though with getting…

TURNER: But it’s a long story! That would take an hour to tell the story of how we marketed it around the world, but let me just say briefly that a lot of it came out of this mind, to come up with a system, and I personally went around and made sales calls and almost, not every country in the world, but I made repeated sales calls in China, in Russia, and in France and Italy and India – I only went there once, but I came away with an order. You don’t need to go back if you get the order, right? My father always said, “Get the order and then leave.” Don’t stay around and give them a chance to change their mind.

TURNER: But we sold it and we delivered and we made profit and that’s what you’re supposed to do in a capitalistic society. We made profit off the commies.

MAXWELL: Most of them, too – quickly.

TURNER: That’s right. But we were good partners. One of the things also that was a secret of our success – I alluded to it earlier by reaching the conclusion that I could live very nicely with 10% of the profits and let the cable operators have 90%. Besides, the cable operators had a lot of leverage, too, and I didn’t think I could get much more than that.

TURNER: If you want to know the truth. I thought if I’d gone for 20% there might have been a little more resistance. Anyway, but what we did is we always gave people a great service at a reasonable price and we gave a lot of good service and we were loyal to the industry and we stood shoulder to shoulder in Washington whenever we were needed. Wherever we were needed to do the little extra things that a company did to serve the industry, we were always there. I got on the NCTA board. I mean, I was the one… I can remember when they didn’t even let programmers be members of NCTA. I said, “Why can’t we join? We’re interested in cable! I know we’re not cable operators, but it says cable association. We want to join the cable association. We’re a cable programmer.” And finally they let us join. First we had to be associate members, you know, second class citizens, kind of like in the South before the civil rights movement. But they never put the dogs on us or sprayed us with water hoses, it wasn’t that bad. But finally they let us in and before it was over, I was chairman of NCTA. I’m the only programmer that’s ever been NCTA chairman. No other programmer’s done it and some people they’ve even recycled, like Bobby Miron’s been chairman twice and so has Joe Collins. They were both introduced and they asked me to run for second term, but I was too busy. But I did fulfill my first term and I’m very proud of it. I really do love this business and I love the people in it. Now that it’s coming to an end for me, I think everybody believes it, but I wanted to say it just one more time because my best friends I made in this business. Most of them have all ready sold out. I mean, there’s only four or five companies left and I predict within a year there will only be two. Maybe it won’t have cleared the government regulatory agencies, but there won’t be but two cable companies left. And I think it’s sad. And there are only going to be four or five programming companies left because everybody’s consolidated with the networks and consolidated with each other and I think it’s sad that we’re losing so much diversity of thought and opinion that we’re going to have just a few companies that some of which, like News Corp, that really only care about their own power and don’t care about the good of society. One of the things we always did is we did care about what happened in our country and we wanted to be a positive force in this country with our programming and a positive force in the world and I think it had a halo effect over the whole cable industry. We cast ourselves as the good guys and a lot of people believed it and it was one reason why we were so successful in Washington for such a long period of time when we came up against the entrenched broadcast interests. We did a lot of things right or we wouldn’t have been as successful as we were and we should be proud of what we did and we are proud of what we did and we deserved every penny we made. As far as I’m concerned we should have made more. We left a lot on the table. Well, not a lot. We left a little bit.

TURNER: We didn’t leave any more on the table than we thought we had to.

MAXWELL: So which two companies are going to be the survivors?

TURNER: Which companies will survive? Well, remember, it depends on how long we’re talking about because look at Time Warner. Time Warner I merged with four or five years ago and they’re already gone – they’re part of AOL. Look at AT&T. AT&T was around forever and it won’t be here in two years. There won’t be an AT&T in two years. They’ll just sell everything off I predict, and I could be wrong about the timetable. It could be three years, but basically. So I would say in the interim, AT&T Cable is either going to go to one or the other big cable companies. And when that happens, Cox and Comcast, whoever’s left out of the AT&T deal will merge with… If AOL Time Warner were to get AT&T that would force Cox and Comcast to merge together probably. So there you are with just the two players not counting Charlie Ergan, if he’s successful as he probably will be. He’s not a cable operator but one of the reasons these last two mergers will go through is because satellite is a very, very real, serious competitor to cable and otherwise the government would never let it get down to two operators and I don’t see how they’ll ever let the last two merge. But that could happen. At one time AT&T had all the phone companies basically. It could conceivably be that Comcast, Cox, AT&T and AOL Time Warner will all merge, you know, and there will just be one company. But I don’t think it would be good for the country.

MAXWELL: No. It wasn’t good the other time either.

TURNER: No. But obviously, in the interim, you’re going to have CBS is going to survive, at least for a while, ABC is going to survive for a while, Fox is going to survive for a while, unfortunately. They’re the worst of the lot. Although, Mel Karmazin, you know, he was stealing money from his advertisers, compressing those commercials down and they got caught, right? I can remember a few cable operators, not very many, that covered up our spots against their contract and were selling them to local advertisers. But we caught them. We didn’t have to turn them into the police or anything. We made a couple of phone calls and they said they’d stop doing it, you know. And I think Mel Karmazin will stop doing it too. But, I mean, there’s stealing going on. A little bit.

MAXWELL: A little bit. Kind of normal.

TURNER: People have been stealing cable for years.

MAXWELL: DBS has a serious theft problem these days.

TURNER: Right.

MAXWELL: So what are you proudest of?

TURNER: I’m sorry, what?

MAXWELL: What are you proudest of, looking back at your accomplishments?

TURNER: I’m proudest of my family. Family comes first and after that, I’m proudest of my accomplishments in television. CNN, probably singly, but individual programs like Cold War, Captain Planet on the Cartoon Network, Portrait of America, Gettysburg. Programs. I like programming. I always used to say to the cable operators at the beginning and during the middle, “You guys string the wires and we’ll make’em sing.” Show business; I like show biz. Remember that song, There’s No Business Like Show Business. I enjoy show business. Gone with the Wind and everything – that meant something to me.

MAXWELL: You’re busy now in developing programming, right?

TURNER: I’m sorry?

MAXWELL: You’re developing programming?

TURNER: Yeah, I’m doing an independent movie. I’m doing a 53 million dollar movie; it’s winding up shooting up in Maryland right now, the prequel to Gettysburg. It’s named God and Generals from the book and it will be out sometime late next year and it’s going to run on HBO and on TNT. Warner Brothers is going to distribute it and I’m doing an 8 hour series with the Nuclear Threat Initiative, which I started with Sam Nunn, a documentary series on weapons of mass destruction. It was already in progress, we’d already started working on it before the World Trade Center and the anthrax scare. It was a little bit ahead of its time, but it will be out sometime next year and it’s going to run on public broadcasting. The new management at the AOL Time Warner cable systems doesn’t have the same commitment to pro-social programming that I did and they are basically closing down serious documentaries to a large degree. But we’ll just go with public broadcasting. They do care about what happens. Maybe I’m being a little harsh, but they’ve closed down the environmental units and there’s not going to be, I don’t think, the diversity of programming that there was before. But that’s okay, they’ll make more money, I guess. I hope.

MAXWELL: Yeah, you still own a little bit, right?

TURNER: That’s right. I hope they make a ton, since I’ve got mostly their stock.

MAXWELL: That’s right. What else are you busy doing these days?

TURNER: I’m starting a restaurant chain. Ted’s Montana Grill. We’re going to try and put one in Denver if we can find a good location, and a couple in Columbus, Ohio. We’re going to build ten and see how they go. Basically, they’re going to specialize in bison burgers and bison meat products, but we’re going to have beef too, just in case somebody doesn’t want bison, and we’re going to see if it works. I’m hopeful that it does because I’ve got 32,000 bison and I’m trying to move some meat.

TURNER: I’m trying to sell some meat. There’s nothing wrong with it.

MAXWELL: No. I could go for one of those.

TURNER: It’s FDA approved.

MAXWELL: So, you have a little bit of land, too.

TURNER: I do. I have a lot of land. A lot of it’s desert, but I do have quite a bit of land and I get quite a great deal of pleasure from my land and I’m hoping that Jerry doesn’t get control of it so he can fire me from that, too. I’m not public and I own it all, but if he could get his hands on it, he probably would. I’m going to do everything I can to keep anything else I have out of his hands. He’s got most of what I cared about right now. He doesn’t have my children either.

MAXWELL: So, this group here is representative of the cable industry and I wonder if you have some advice for them going forward?

TURNER: Well, gee… I can’t think of any. I didn’t think you were going to ask me a question like that. I mean, the older guys are already pretty well off. I don’t know. That one kind of left me speechless. We’ve had so much communication over the years, they all know what I think and I know what they think pretty much.

MAXWELL: What would you do differently if you had a chance? Besides…

TURNER: I told you, the biggest thing I would do is I would have made the consortium work without Time Warner and then I would have had NBC five years ago and I would have bought Time Warner about four or five years ago and I would have fired Jerry instead of him firing me!

(LAUGHTER, CLAPPING)

TURNER: The trouble is, I didn’t even think of firing Jerry. When we did the merger, he was carried away at one point – because I really think he’s basically a good person – but he said to me, “Ted, you’re my best friend.” I said, “Jerry, I’ve never even been in your home. If I’m your best friend, who’s your second best friend?” He said, “Nick Nicholas and Michael Fuchs.” No, he didn’t say that, I added that.

MAXWELL: I know he didn’t say that.

TURNER: But he did say the other, and I was his friend. I would have had a hard time firing him. At that time.

MAXWELL: I wonder if anyone in the audience has any questions they might have for Ted. He’s willing to accept a few if we have a microphone here.

TURNER: Just don’t ask me too hard of one.

Audience Member 1: Hi. I’m Katie Harris, a media columnist for Bloomberg…

TURNER: We can’t hear you. Can you pull that microphone down a little bit?

MAXWELL: Right. Thank you.

Audience Member 1: My question was, did Dr. Malone advise you not to let Time into the consortium or Warner, because they were not merged at the time.

TURNER: They were in the process of… that’s a good point. That’s right!

TURNER: I think Time was what John was most concerned about and Steve Ross’s health was not good. Actually, Time Warner merged during this period of time but I think they were already merged when I agreed to merge. Time Warner had completed their merger when I merged with them. It was a race to see who could merge first. That was another reason, I wanted to see what it was like to be part of a big bureaucratic company, because I just wanted to see in my adventure. I was getting hold and I’d never been part of one of these big companies and I wanted to see what it was like. It’s miserable. No, it’s not that bad. It’s not as good as being entrepreneurial, I’ll tell you what. I enjoyed the entrepreneurial phase better. Yes, ma’am.

Audience Member 2: Yes, Doris Lee McCoy from McCoy Productions in La Jolla. And I was just wondering, Ted, if you, looking ahead, what kind of programming would you like to see becoming a part of, that you could instigate? Because of your interest in the environment and other things, what kinds of topics would you choose?

TURNER: Just the things that we already did. We did a lot of environmental programming, did a lot of documentary programming, National Geographic, we ran that for years.

Audience Member 2: Cousteau?

TURNER: We don’t run it anymore, or the company doesn’t. “We” is probably not the right term, but I still think that way. Nothing that isn’t already being done. There’s a lot of good programming being done out there by a number of people, a number of companies.

Audience Member 2: But I was thinking about you specifically.

TURNER: Well, I just told you – I’m doing a movie, the prequel to Gettysburg and if it’s successful we’ll probably do another one. I’m not going to try and… the movie business is a terrible business as a stand alone business, so I’m doing it just out of, not to make a lot of money, but just because I want to keep my hand involved in programming because I like it. And that documentary series that we’re doing for public broadcasting, which the working title is Avoiding Armageddon about how we reduce the threat of weapons of mass destruction. That’s right up my alley as far as pro-social programming is concerned.

Audience Member 2: Thanks, very much.

TURNER: You’re welcome. It’s Elvis Presley!

Audience Member 3: Mr. Turner. I like that. I’m from Television International Magazine. I’d like to ask you: what haven’t you don’t to fulfill your life?

TURNER: What haven’t I done?

Audience Member 3: Yes.

TURNER: Well, I never got a network. At one time that’s what I thought they were going to engrave on my tombstone but I’ve gone past that now and I’m going to have engraved on it “I have nothing more to say.”

Audience Member 3: Thank you, Mr. Turner.

TURNER: I’d rather be here than in Philadelphia.

MAXWELL: That’s right.

TURNER: Except Brian Roberts doesn’t feel that way.

Audience Member 4: Mark Millet. You had mentioned that you saw Internet as a competitor. How do you see that the cable operators can benefit from the Internet and also bring that in and bring out its values and opportunities for social improvement?

TURNER: I’m sorry, I heard the first part.

Audience Member 3: How do you see that the cable operators can help the Internet bring out its values and opportunities for social improvement as a communications media?

TURNER: I didn’t say that the Internet was going to bring cultural improvement.

Audience Member 3: I said how do you think the cable operators can do that, can help that happen?

TURNER: I don’t know. I really don’t. I’m leaving the future to the next generation. It’s hard enough for me to keep up with the present and the past.

Audience Member 4: Ted and Paul, this is Dave Kinley from Sun Country Cable. I was hoping to hear a few more personal anecdotes, so I’m going to try and tee one up. The first time I met you, I was working for Monty Rifkin and it was down at the old baseball stadium and that morning you had your face all covered with bloody scabs because of a stunt that you had pulled the night before in promoting the Braves. I don’t know if you remember it?

TURNER: Oh, I remember it!

Audience Member 4: Do you want to tell that story?

TURNER: I pushed the ball from first base to homeplate faster than Tug McGraw of the Phillies pushed the ball from third, with my nose. On my hands and knees.

Audience Member 4: I wondered what led up to that and why you decided to do that and while you’re talking about that, would you like to talk about the future of baseball and whether it will be contracted.

TURNER: Hey, look! Wait a minute! We’ve only got a couple of minutes. The future of baseball?! Let me tell you – Ken Burns did fourteen hours on it. That would fill encyclopedias, but I did it, basically, our promotion director came up with the idea that I would do it and I played along with it and I wanted to win. So I pushed harder than Tug McGraw did and I beat him by about five feet. He didn’t have any blood on his nose, but I… unfortunately when you’re pushing a baseball with your nose, if you push it real hard and particularly over the gravel in the base path, you know, and not on the grass – that’s where the ball rolled and I had to push it there – you’re going to scrape your face up pretty bad. But I didn’t need any stitches. I survived.

Audience Member 4: That’s good.

Audience Member 5: Clint Stinchcomb, Discovery Networks. Ted, you talked about the broadcast networks that you were real close to buying, what about the cable networks? Were there any that you were real close to buying that didn’t go through?

TURNER: Well, I would have liked to have bought them all, at one time or another, but I couldn’t do it for a number of reasons. There was a period there where the cable operators realized that by allowing these cable networks to do on their systems and to pay – you see, I got in there too early, or too early for them to figure out that I might make money. They were concerned about whether we would stay on the air and survive, but by the time Discovery came along, they’d figured it out and they wanted to own the cable networks as well as the cable systems and that’s why John Hendricks and the management team own 2% of Discovery Channel and the cable operators own 98%. So, I got in early for that, but it was very hard to buy cable networks. Malone was the 800-pound gorilla and he’s been a close friend of mine and everything and he is today, but he wanted to own the networks too and it made it very difficult for independent programmers to do well, because once again, the timing was such that the cable operators weren’t as generous as they were at the beginning and they wanted to get as much of the equity of everything as they possibly could, and I don’t blame them at all. I would have done the same if I’d been them.

MAXWELL: Okay.

Audience Member 6: I’m Michael Lambert.

TURNER: Yeah!

Audience Member 6: How you doing?

TURNER: I remember you from somewhere.

Audience Member 6: From Viacom in the old days with Ralph Baruch.

TURNER: Where have you been, Michael, the last 30 years?

Audience Member 6: Well, still in the business.

TURNER: Still alive!

Audience Member 6: Still alive. I’m thankful for that. I own some TV stations. Not large markets.

TURNER: What are you doing here?

Audience Member 6: Medium sized and small market TV stations.

TURNER: That’s not so good.

Audience Member 6: Well, that’s what I’m asking you about.

TURNER: There’s only one thing that’s worse than small market cable systems and that’s real small market cable systems.

Audience Member 6: So here’s the question, and now we’re being faced with of course the downturn of the advertising market and the single revenue stream. What’s your advice for over-the-air broadcasters?

TURNER: Well, that depends. I wouldn’t want to be a stand alone broadcaster and the networks now own most of the cable networks that amount to anything. So I would say, I’d get out of the business if I could, but it’s not easy. You probably owe more than they’re worth. You’re timing wasn’t good if you’re still in it. You should have gotten out three or four years ago, but get out when you can, if you can. Merge with somebody… the small market, over-the-air broadcasters are in deep trouble.

Audience Member 6: And you think news, local news, and the production of quality local news casts…?

TURNER: The really smart person will figure out a way to survive, but it’s not a good place to be, and you figured that out too. All you’ve got to do is read Broadcasting and Cable Magazine and you can figure out you’re in trouble. And I’m sorry about that. I feel sorry for those that the timing wasn’t right. Hopefully the market will come back, but the next time the market turns up for those little stations, sell’em.

Audience Member 6: Well, we sold a few of them along the way. We did okay.

TURNER: Okay. Well, that’s good.

Audience Member 6: But do you think there’s a consolidation move and do you think local news has a place in…?

TURNER: Of course there is. Local news, you can run local news on a station as part of a chain. You do it yourself. You said you’re a multiple operator, right? There’s room for local news, of course.

Audience Member 7: My name is Bill Selig and I’m president of ???? Human Sciences, a nonprofit, it doesn’t make any money, and years ago I wrote you a letter about this water from Canada and you wrote me a little note back saying I’m not in that business, but I believe in environmental things and development and everything else. Now the mistake I’m making now is I’ve been trying to raise money for movies. I’ve got the Joe DiMaggio story and I’m trying to stay out of the movie business. I’m also…

TURNER: I can’t hear a word you’re saying. I can hear you but I don’t understand you. Would you ask a question?

Audience Member 7: You mentioned about not having much environment anymore in cable and I want to get alternative medicine to cable. You can’t become a cable network anymore, you have to sell to the cable boys, is that correct?

TURNER: I don’t know. What’s the question?

MAXWELL: The question is…

Audience Member 6: The question is…

TURNER: Hold it a minute. I can’t hear you, I can hear him.

MAXWELL: He’s asking about programming versus networks and how to get his ideas on and that’s probably something for another session.

TURNER: Yeah, that’s too long to handle here today.

Audience Member 6: Because what turned me on was you said that they’re not doing much environment anymore and other things like I wanted to put on alternative medicine on cable because they don’t have enough of that now.

TURNER: Well, good luck and do it. There’s nothing stopping you from doing it. Good luck. I like alternative medicine. I’m not sure it works, but I’m not sure regular medicine works either.

Audience Member 7: But I like your fortitude, your fight.

TURNER: Okay. Appreciate it.

Audience Member 8: Ted, what would you have done with a CBS or an NBC if you had acquired it?

TURNER: What would I have done with one of the networks, had I gotten it? I would have combined the purchasing power… see, the guy who wins, the big winner is the one that puts the greatest amount of purchasing power together so that they can own the Olympics, so they can own the Academy Awards, so they can own the NFL, so they can own the NBA Finals, and you’ve got to have a major network to do that. You’ve got to have more than just the purchasing power and I could see we were not going to have the purchasing power without a network to do it because some of these programs, like the World Series, like the Super Bowl, like the Academy Awards, you can’t buy with a cable network no matter how much money you have because the rights holders won’t sell them to you because they want 100% exposure and I think that’s right. If one of the cable networks had bought the World Series and the Super Bowl and made people, forced them, to buy cable in order to get it there would have been a reaction against the cable industry that would have been worse than the additional penetration that we would have gotten. So, the winner, the winner, at the end of the game, like in Monopoly, you have to have Board Walk, Park Place, North Carolina, you want to get the blue property over on the left hand side of the board and the green property, all the way down to get out of jail free, or whatever it is. Take a ride on the railroad. You want to own the prime real estate and any company that didn’t have that was going sooner or later be a marginalized player and I think that’s basically what’s happening to the Time Warner cable networks now. We’re making a lot of money and we will for quite a while, but making money… I wanted to win too. And usually, the guy that’s in the number one position, you get a premium for whatever it is you’re selling if you’re the number one player. Tiger Woods makes the number one salary in golf because he’s the best player. And I wanted to win. When I sailed boats, I sailed to win. When I played the television business and the cable television business, I played to win, and I’m not satisfied with being with a second rated operation. So, I kind of feel like in a way, Jerry’s done me a favor. It’s been very painful making the transition, but we haven’t talked at all about the philanthropy that I’m doing. Last year I gave close to 250 million dollars away. That’s a lot of money to give away if your stock is down like AOL Time Warner is, like everybody else’s stock is down, but I think it should be higher than it is. Of course, I always… if you think like a winner you always feel like your stocks ought to be higher, but I’m doing other things now that are quite interesting, like most of the cable operators that have sold out. They’re doing interesting things and a lot of them are doing things in philanthropy at the local or national level. I mean, what are you going to do with all this money anyway? If the stock keeps going down we won’t have to worry about it, because we won’t have it anyway, but at least we’ll have given some of it away while we did have it. Wouldn’t it be terrible to hang onto every nickel, like Rupert Murdoch and who’s the guy with Viacom, our good friend…?

MAXWELL: Sumner.

TURNER: Sumner Redstone. They don’t have even small foundations. Neither one of them would give away a nickel basically. If they loose all their money they won’t have gotten anything to show for it. At least we had the fun of giving some of it away. What’s your questions, young man?

Audience Member 9: Hi Ted. Oliver Chin with Interactive TV Today. I was wondering what your opinion is of interactive television and its growing importance to the cable industry?

TURNER: I think interactive television is great. I want to be able to see what I want to see when I want to see it. But basically, when you’ve got a VCR and videocassettes or a DVD, you can see what you want to see pretty much when you want to see it. If you’ve got cable you can turn the news on any time you want to see it. I don’t particularly care about seeing yesterdays baseball game today, so being able to watch sporting events, but already you can get just about any sporting event if you’ve got the right combination of networks, you can see any game just about that’s being played anywhere in the country. I don’t think it’s that big a deal because we already have pretty much interactive television today. It’ll be a little better… I mean, I don’t really care about seeing the WB show that ran last Monday. I didn’t watch it when it ran on the WB and I ain’t gonna watch it if it’s available 50 goddamn times. It’s still crap as far as I’m concerned. And that goes for CBS, NBC and ABC too. I wasn’t going to buy’em to watch’em; I was going to buy’em to make money on them.

MAXWELL: We’ll take two more questions here.

TURNER: Thank God, we’re getting near the end.

MAXWELL: We’re getting close.

TURNER: Mercifully.

Audience Member 10: I’ll be short winded then. I’m Randy Campbell with Superior Communications. I started my career in Dalton, Georgia in the late ’60s, early ’70s. I remember a station, WTCG that was the first one not to run a test pattern at midnight for the rest of the night.

TURNER: We were the first station to go 24 hours a day 7 days a week.

Audience Member 10: And that was very refreshing when I was in my early 20s to see that and we sold a lot of cable because of it.

TURNER: What’s the question?

Audience Member 10: The question: since you don’t have a job now, you wouldn’t have any conflict of interest, what do you think about maybe running for office?

TURNER: I’ve thought about that and I think I’m probably too burnt out and too old for it. It takes a younger… the last two presidents we’ve had have been much younger men and the last old president we had has got Alzheimer’s. It might give you Alzheimer’s. I can’t remember whether I’ve got Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s already. Who’s the next question?

Audience Member 10: If you change your mind I’ll vote for you.

TURNER: I ain’t gonna run. I just don’t have the energy to run. If I ran I might get elected and then what am I going to do? I don’t mind going to Washington to lobby, but I don’t want to have to live there. I mean, the White House is only on about 5 acres. That’s too small for me. Camp David is only about a 1000 acres. Too small.

Audience Member 11: Mr. Turner, it seems like a lot of your career was visualizing things that didn’t exist at the time, especially when you were in your 20s as an entrepreneur and went out and created them.

TURNER: Yeah, yeah.

Audience Member 11: If you were starting today as a young entrepreneur, what do you think you might do?

TURNER: Well, I’d have to think about it and look at what all the options were and then decide on what my plan would be. I’d work out a very careful plan, but since I’m not going to do it, I’m thinking about other things that are more relevant to me now at 63. So you have to figure it out yourself. I’m not in the advice business, for Christ’s sake. Send me a check for a hundred grand and I’ll give you a one-liner.

Audience Member 11: Would you be in the television business?

TURNER: I don’t know. It would be hard for me not to be in show biz in some sort of way. You know, remember the song, There’s No Business Like Show Business. I like show biz.

MAXWELL: No kidding. We’re wrapping up this oral history at the moment. We have one more thing to do. We auctioned off a poster of Ted from his when he was cool and cable wasn’t yet and the winner was Bill Bresnan, who is right here. And if you’ll come up and get this, you’re going to get it from Ted.

(CLAPPING)

TURNER: Thanks, Bill. Here you go. Okay pal, good to see you. Thanks for being here.

MAXWELL: That’s it, ladies and gentlemen and we really thank Ted today. Thank you.

TURNER: Thank you everybody. Appreciate it.